The apocalypse of Alan Moore

How a Tarot-influenced comic book changed minds and ended the world

I spoke to Jessa Crispin in the last part of this series on creativity and Tarot about artists ideally yoking together two forces, à la the Chariot card: the conscious and the unconscious, rational judgement and intuition. But doesn’t most human activity combine these? The point then, especially for artists, is to get the balance right.

For Italo Calvino the surrealists skewed too far one way, surrendering passively to the unconscious, hence textual cut-ups, automatic writing, music composed by the notes that a palm frond strokes on a harp and other such aleatory techniques—a kind of artistic prosthetic.

But Calvino’s own chariot was skew-whiff the other way. In the first part of this series I covered how a Tarot deck helped him write his novel The Castle of Crossed Destinies. As the Tarot is supposed to foretell your future, so he used hands of Tarot cards to tell the stories of his characters. His method was meticulous, logical, composed of “ironclad rules”, and he was content with no grand design beyond the one his intersecting storylines made.

This, to my mind, is why the novel is a diverting and fascinating nice-try more than an accomplished work of art. Calvino honoured the systematic method of magic but he neglected the wider, wilder world on which it’s meant to be window, the world that gets called elsewhere, “the holy splendor of the human imagination.”

Has anyone else managed where he failed? What is the great art of and about magic? Which artworks struck a better balance?

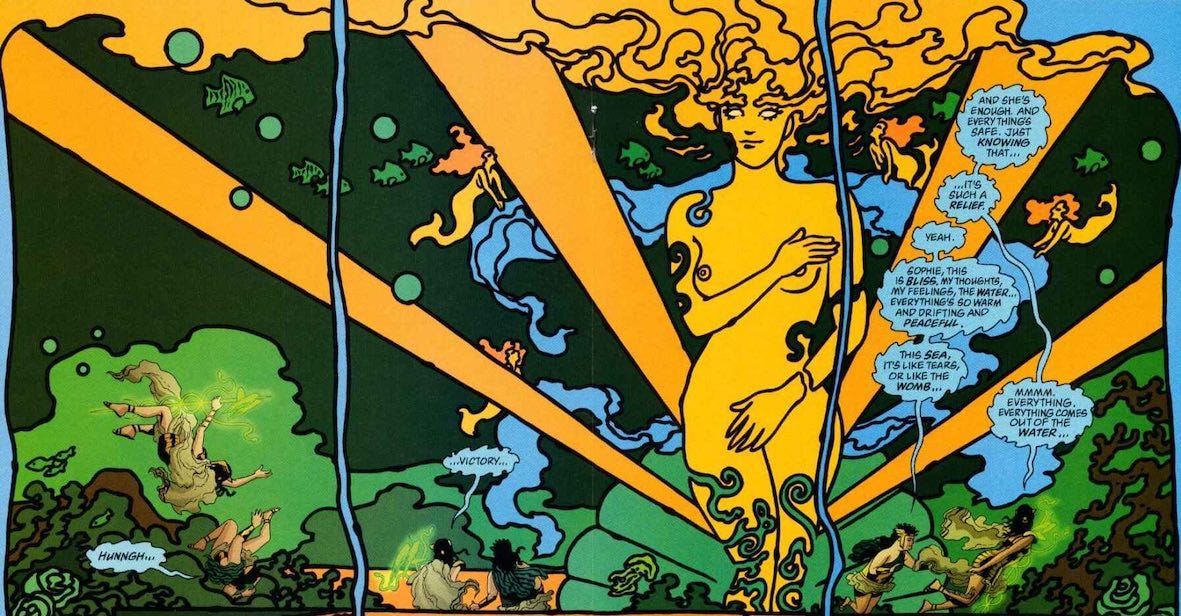

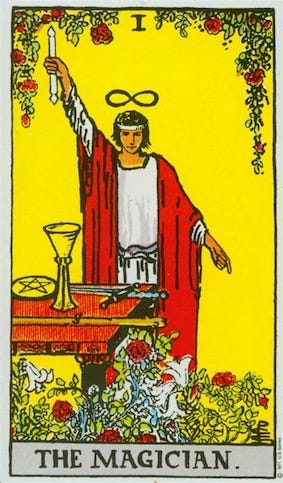

This one:

Written by Alan Moore and illustrated by J H Williams III, Promethea is about a student called Sophie Bangs and her friends who, in New York in 1999, become avatars of a figure called Promethea, a demigod-like being who draws her power from that potentially infinite realm of the imagination variously labelled in the comic as magic or art.

Alan Moore is one of England’s greatest ever artists and Promethea is him working at the height of his magical powers. But the comic remains one of his lesser known works, in a medium that’s still lesser read (despite the two-prong attack of gentrification and popularising-through-adaptation). I don’t want to do any particularly deep-read/deep-look at the comic; besides there are already plenty of annotated versions and panel-by-panel analyses. Instead I want to figure out how to make the case for Promethea without preaching to the comic-savvy or falling on the deaf ears of the comic-agnostic. To help me, and to round off this series, I drew a hand of Tarot cards. And what do you know, they resonated like a tuning fork.

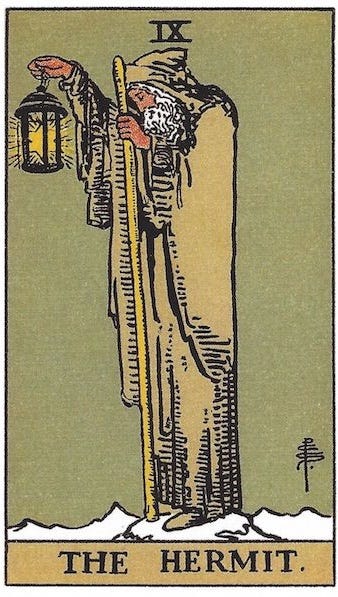

The Alan Moore of the popular imagination is just that, a hermit, a hard-to-reach nonline Luddite who once told GQ magazine he hadn’t left the UK since 1989. For almost as long, he’s exiled himself from the comics mainstream, and been froward with his rivals, peers and perceived enemies. In 2019, Damon Lindelof wrote an open letter to the adaptation-averse Moore about his love for the man’s Watchmen comic and his plans to make a TV sequel of it. Moore was decidedly not sweet-talked.1 Zack Snyder, the director who’d adapted the same comic into a film a decade before, got a similar reception: Snyder had said his best hope for how Moore might react to his film was that on “a rainy day in London” the man would catch the film on TV and think it not half bad. Moore snapped he didn’t live in London but Northampton.

Now, Northampton is hardly the shore of the Black Sea to London’s Rome. Moore himself has made the case for the town being the historical, geographical, psychogeographical centre of England. Its place in history and the country is Moore’s ideal vantage from which to make his art. As Calvino wrote in The Castle of Crossed Destinies:

The hermit’s strength is measured not by how far away he has gone to live, but by the scant distance he requires to detach himself from the city, without ever losing sight of it.

Moore never lost sight. For a hermit, he’s never scanted on interviews. He remains world-famous while avoiding most of the trappings of celebrity, remains politically and culturally engaged while staying off the daily-nonsense grind. It’s the kind of stance that led author Iain Sinclair to call him “the sanest man in England.”

He also sometimes gets called a latter-day William Blake, one of his own heroes. Between the visionary comics writer and the visionary poet-painter it’s easy to draw a prestigious, ancestral link. But Moore is as much the cousin of Mervyn Peake, Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett. Like them, his tone, his interests, his sense of humour are very English. An early comic, Skizz, Moore described as E.T. crossed with Boys from the Black Stuff. (Its refrain came from an unemployed pit miner: “I’ve got me pride.”) His expertise in English history and art tends towards the kooky and curio. It’s that mix of the arcane and everyday, the profound and silly that gives him his power. He’s not a world-denying hermit; reclusive as he is, he is at bottom our great popular artist.

Then maybe the Hermit more stands for the art-form of comics itself. In Promethea we see the card like this:

The Hermit is the foetus, literally as a stage of a human being and of human culture at large: the gestating, the immature. Is this where comics are at, even in 2023? Surely they’ve long since been disinterred from the underground? Except that Marvel’s supremacy in the cinemas has had an odd reversal effect. We don’t really think of them as comic book movies any more so much as superhero or even just Marvel ones. Notwithstanding that comics can now pass as novels under the term ‘graphic novel’, and occasionally appear on end-of-year best-of lists of cultural luminaries, they’ve still not shaken the image of Comic Book Guy from The Simpsons. We still use the cliché of his real-world ilk living in ‘mom’s basement’, that other symbol of the womb. (Anyway shouldn’t it be ‘dad’s attic’? Isn’t that where the boyish hobbies of yesteryear usually gather dust?)

If anyone forcepped comics out of the womb it was Alan Moore. The high summer of his career also helped birth that unkillable journo cliché, ‘Comics aren’t just for kids any more!’ There was the antifascist romance V for Vendetta; the superhero de-and-reconstructions Marvel-sorry-Miracleman and Watchmen2; and the why-do-it Victorian crime drama and masonic exposé From Hell. But then came Moore’s barnstorming autumn—his America’s Best Comic days that feature his funnest and sunniest work: the healthily nostalgic Tom Strong, the pre-Top Shelf The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and a series that crossed superheroes with police procedurals, Top Ten, Smax, and The 49ers. Then there was Promethea.

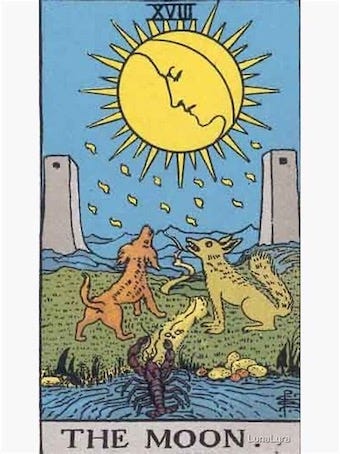

This is the next card I drew, which in its reverse aspect is a symbol of fear of faith in intuition. In part 2 Jessa Crispin called our culture intuition-impoverished. What about the other end, what about culture that’s intuition-overstuffed? Shouldn’t we be wary of that?

It’s never been hard to find: just go to your local occult shop and browse the shelves of prophecies, narrated third-eye visions, dictations taken from guardian angels. Or read upbeat modern magic how-to’s like Post-Colonial Astrology. Magic can be silly and so obviously, off-puttingly divorced from the real world. And this was always a danger with and criticism of Promethea.

On a plot level, Sophie Bangs and her friends’ have various colourful adventures and trials as Promethea, battling her old demons, the FBI, a team of interfering ‘science heroes’ called The Five Swell Guys. But most of all they learn about Promethea herself, what she’s for, and so learn about the world from which she comes and incarnates.

In The Castle of Crossed Destinies, Calvino described the Moon card’s “pale fields… where an endless storeroom preserves in phials placed in rows the stories that men do not live”. In Promethea this is called The Immateria - not dissimilar to The Dreaming in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman universe - the world not of facts but possibilities, ideas, ideals, not knowledge but make-believe stories. This is Promethea’s territory, what she named “the holy splendor of the imagination.”

And it’s Moore’s real subject. The point of Promethea is to champion magic as the way to understand those imbricated messes, mind and matter, consciousness and reality, the immaterial and the material. That’s because, for the comic, these sides are in a positive feedback loop, one which runs on language, of which art and magic are especially concentrated and potent forms.

To relay all this Moore hasn’t just composed his comic with the help of magical systems; he uses them to teach us about them. The whole comic is a magic spell, its payoff being to make you believe - sensibly, reasonably - in magic. What

in his preface to a piece on Tarot would call “mysticism sublimated through the rigours of scholarship”.And so in issue 12, Sophie as Promethea spins through the Tarot as a way to tell a magic-inflected history of the universe. Then from issue 13 onwards she takes a tour with previous Promethea avatar Barbara as her guide to a netherworld, like Dante and Virgil before them, but not through the pits and peaks of the afterlife but up and down the spheres, or sephirot, of that map of the celestial and divine known in the Hermetic Kabbalah as The Tree of Life. (In a further cute coincidence with the card I drew, the Moon is the first sphere Sophie and Barbara attain in their vision quest.)

And here’s where your eyes begin to roll and your finger begins to scroll… But this was the same danger Moore and Williams courted. That the reader would find all the magic stuff, storied and intricate as it may be, a bit abstruse and tedious, not least for a SF/Fantasy comic.

To this charge Moore protested, “There are 1000 comic books on the shelves that don’t contain a philosophy lecture and one that does. Isn’t there room for that one?”3 And the style of his ‘lecture’ is far from abstruse. Moore himself remarked on the roots of the word ‘occult’ - hidden, secret - as entrenching the image of magic as elitist and obscurantist. As for himself, he said, “I wanted to do be able to do an occult comic that didn’t portray the occult as a dark, scary place, because that’s not my experience of it… [Promethea was] more psychedelic… more sophisticated, more experimental, more ecstatic and exuberant.”4 Whether in story-mode or lecture-mode Promethea is exactly those things. Which brings us to my next card:

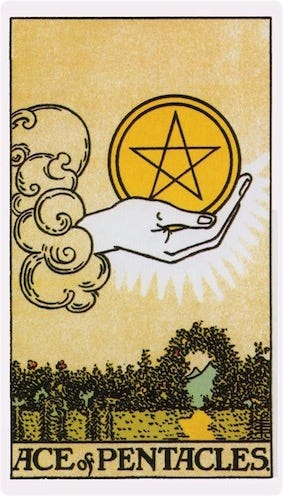

This card means wealth, riches, abundance, or the chance of them. (The agricultural backdrop symbolises seed-like potential, the ace the first step to fruition.) The card can even, conveniently for our purposes, mean the third eye or the alchemist’s gold.

If Alan Moore is a hermit, his hermitage is like the one in St Petersburg, a retreat with a huge wealth of art. According to the song by Pop Will Eat Itself, “Alan Moore knows the score”; he also brings the goods. His greatest hits, as well as being supremely satisfying stories and of great historical moment for their art-form, are each a repository of artistic, cultural and historical knowledge. His erudition is low and high brow, and in both cases he’s never snobbily forbidding nor does he underestimate his reader’s ability to get his references without getting chippy. He’s generous with his cultural wealth.

Promethea in turn is a rich compendium of magic: the above-mentioned Tarot and Kabbalah, and also the zodiac, Egyptian and Greek gods, chaos magic spells, visual riddles, brainteasers, word-games, as well as snippets of magicians new and old like Alesteir Crowley and John Clare. (It’s as if Promethea is the narrative version of Alan and Steve ‘no relation’ Moore’s forthcoming The Moon and Serpent Bumper Book of Magic, a combined grimoire, occult encyclopaedia and rainy-day activity book.)

And that’s just the magic parts. First published in 1999 Promethea is suitably millenarian in its teeming forms. Moore once told an interviewer, “My experience of life is that it is not divided up into genres; it’s a horrifying, romantic, tragic, comical, science-fiction cowboy detective novel. You know, with a bit of pornography if you’re lucky.” Promethea has all of these, all meaningfully tied-in and lovingly pastiched.

And so in a comic replete with superhero pow-biff action, diabolically corrupt mayoral politics, even musical satire (there’s a repeated walk-on by a band called Limp, a cross between Pulp, Suede and Morrissey) why shouldn’t it include the form of the picture-essay on magic?5 This is true polyphony, this is riches.

Promethea is more than a wealth of content. The Eight of Pentacles shows a skilled artist at work, his previous creations stacked like trophies. This is the card for the ‘art’ in ‘artisan’ or ‘artful’. Promethea isn’t a formless grab-bag of everything Alan Moore knows about magic. It’s one of the best examples of his comics craft.

I wrote previously about films we praise for being so cinematic, and why Ulysses should be praised for being such literary literature. Promethea meanwhile is the most comicy of comics.

Moore’s always been a formalist—fuelled, true, by his original and far-out imagination but tempered by a thorough integrating of form, style and content. Everything in Promethea has a point, warrants its presences, ties together, at the micro and macro level. The magic lectures are not like those say-what-you-see ‘a beginner’s guide’ / ‘introduction to’ [insert topic] books which were so popular a few years ago. They show and tell and embody. Panels melt when Sophie and Barbara meet the mercurial god Hermes; when they reach the Sun the panel grid is not rectilinear but radial; a section on infinity is a Möbius comic strip; there are collages; visual homages; breath-catchingly spooky moments which break the fourth wall (or fourth panel? fourth dimension?). Promethea is full of trick-shots like this, guitar solos, coups de théâtre. It leads by example to show you what the medium can do. It teaches you how to read it and how comics can be read, and does so rapturously and unstarchily.

In one of the peaks of its brilliance, issue 12, Promethea twirls in space while in conversation with the two serpents on her medical-symbol-like caduceus, one called Mike (for microcosm) and Mack (for, you guessed it, macrocosm). They use the 21 cards of the Tarot’s Major Arcana to tell the history of the universe and evolution and culture, in rhyming couplets, while at the same time the letters that spell ‘Promethea’ are scrabbled, seeing as they’re on Scrabble tiles, into all their possible anagrams - ME ATOP HER, EH TEMPORA, HEART POEM and so on - each one matching each page’s Tarot card and subject matter, and on top of that, or rather at the bottom of the page, Alesteir Crowley grows from child to wizard as he tells a joke which is meant to be the key to existence. It’s the kind of sequence that makes the reader want to yell, good-naturedly, “Fuck you!” But then Alan Moore was never one for modest effects, which brings us to our last card:

Even to the most hard-nosed materialist, certain coincidences are pleasing. Such as drawing Tarot cards for a piece on Alan Moore and the last being the above. (You’ll have to take my word for it, but whether you believe me or not doesn’t change the magic trick gasp-and-laugh of it all.)

Moore, in many interviews since his 40th birthday, has spoken about his decision to become a magician or wizard. While he’s performed public magic rituals since, his biggest magic trick has been Promethea. Through Sophie’s story and how he tells it, Moore wants to reassert magic’s place in the world, and make the case for it being the same as art, and with his art-magic help revitalise culture.

What does it mean to say magic is an art though? Does Moore mean it in the way that everything can be an art if there’s a book to be sold off it? The Art of Pickling. The Art of Javascript. Or is he actually, albeit unwittingly, downgrading art by subsuming it under the parent heading of another cultural practice, in the same way people who make art politics or make art ethics downgrade it, render it redundant? Because, considering you can already get politics and ethics elsewhere, there’s nothing special about art if it’s just more of them. And no one would claim art was the best way to do politics or ethics, so why bother with it at all?

But Moore’s claim isn’t that what we think of as art is actually magic, but that they are and have always been the same. Which is a stronger claim; not exemplification but identity. (Art = magic: is this what I meant by C=D?)

Moore once said “art is propaganda for a certain state of the mind”. It’s how one mind can profoundly change another through the conduit of language. But can’t anything manage that? Talking to someone, giving them drugs, cooking for them? Even science, Dr Jacob Bronowski suggested, inasmuch as it involves ideas changing matter, is magic in the original sense.

Moore is well aware of all the things that can count as magic by his definition. Throughout Promethea we find the antithesis to his art-magic project: forms of magic that are indiscriminate, badly judged, irresponsible. Like what?

For The Castle of Crossed Destinies’ never-written third part Calvino planned instead of the Tarot to use their “modern equivalent”: symbols that feed off the collective consciousness: ads, comic strips. Both appear in the back- and then foreground of Promethea. The comic is full of ads, like Watchmen before it.

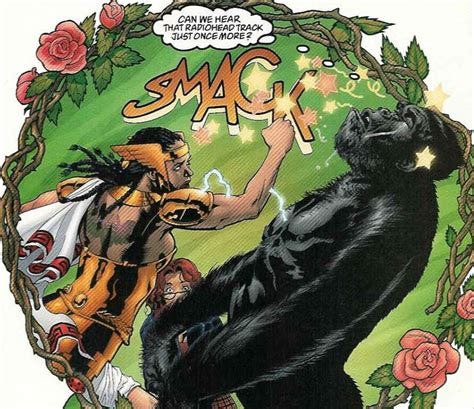

Even (or especially) at the level of ads, Moore warned, language has magic power: “Jingles [on TV] can cause everyone in the country to think the same words and have the same banal thoughts all at exactly the same time.” The most prominent ads in Promethea are ones on billboards for a trendily flip comic strip called Weeping Gorilla, then for one called Chuckling Duck (Weeping Gorilla says things like “Go on. Ask me about my marriage,” and “We probably expect too much of George Lucas.”) Later, in the Immateria, Barbara-as-Promethea has to fight the Weeping Gorilla before she drowns in his nihilism.

Pace Jessa Crispin, these aren’t examples of a lack of magic but degradations of it, not black magic so much as blag magic. A piss-take, unserious, meaninglessly eclectic, with no point other than making money or buffing a brand: magic tricks in all the pejorative senses of the word. The comic is filled with alluring but inane consumer products like Elastagel, bored celebs like the lead-singer of Limp, cynical TV shows, clever-clever ads. What in 1999 was the dominant cultural force of post-modernism.

Moore himself is a kind of post-modernist. Following his alchemist forbears’ M.O. of ‘salve’ and ‘coagula’, that is dissolve and reform, he’s made a career from retooling and remixing older culture: the forgotten Charlton Comic superheroes that became his Watchmen; Alice, Dorothy and Wendy telling one another the true versions of their children’s stories for his comic Lost Girls.

The difference is his sense of responsibility, something he as a professed anarchist cares deeply about. What’s wrong with post-modernism and the more intuition-dependent ends of the avant garde? That their creators can shrug and say, ‘I don’t know what it means.’ Or even, ‘Urgh. Meaning!’ Of course, everything always means something, even if it’s shallow or noxious; these creators just don’t want to take responsibility for it.

Moore’s position here isn’t the popular one of the late 90s and early 00s: that of being ‘against irony’. A comics writer and a comic writer, whose metaphysical stance is a kind of idealism, where language constitutes reality and where whatever we think is real, could hardly be an anti-ironist. Promethea was never part of the call for more sincerity in culture and art. Moore wants more meaning.

Promethea was published from 1999-2005, a millenarian time in a way few expected. After 9/11 (which has a panel cameo in the final pages), and with the comic’s New York city setting and with Moore’s prior form in this area, Promethea seemed set to confirm that old adage of “no millennium without apocalypse.” Which is why as Sophie finds out more about Promethea, she learns what she’s meant to do with her powers: end the world.

In a good way! End as in a purpose, a point. In the comic something like a magical singularity is on the Tarot cards. Unlike the A.I. one, it doesn’t supersede but depends on and includes us, in a maternal way, an enrichment of human consciousness. Instead of the spectacle of catastrophe, the psychedelic ending of Promethea is exultant, inspiring—talk about Apocalypse Wow! Even the sad-core Limp tune in and cheer up.6 This ending justifies the magic lectures we got before, clarifies them as not self-indulgence but integral to the comic’s pay-off. It wouldn’t work without them.

This is what Moore and Williams had that Calvino lacked: a point. That’s not to be down on Calvino; he led the way. And I’d be surprised if, what with Moore’s love of Thomas Pynchon, Wiliam Burroughs and other literary inventors, he hadn’t read Calvino before he wrote Promethea.

And what would you know, The Magician in the Tarot is also known as The Juggler, card number one, which Calvino wrote about in his novel and likened to himself:

[O]nly tarot number one honestly depicts what I have succeeded in being: a juggler, or conjurer, who arranges on a stand at a fair a certain number of objects and, shifting them, connecting them, interchanging them, achieves a certain number of effects.

Calvino’s calling card - the artist as permutater of patterns - becomes our card for Moore, the artist as magician. For the one, art is variations, the value-free churn of everlasting shifts, connections and interchanges. (Value-free like maths has no values.) For the other, art had a start and is moving towards the end: art as history.

We began this series with overly rational Calvino playing with the Tarot within rules. Then Promethea featured magic without rules, rhyme or reason: po-mo relativism, mass media, anything-can-mean-anything woo, cynical flip. This was then judo-flipped by Moore’s make-believe.7 His point isn’t that magic is serious and true but that, whether you believe in it or not, it, like art, changes minds and the world.

At bottom magic is about change, about the immaterial effecting the material. But change shouldn’t be the extra-aesthetic point of art. Giving art a point reduces it, even if that point is as big as jumpstarting the next stage in cultural and spiritual evolution. If art is magic, then it has to be magic for magic’s sake. And yet, since, for Moore, language constitutes consciousness and therefore reality, then the practice of art, the making of art, pure art (as in pure maths) is nonetheless also always a clarification and enrichment of reality.

Plato thought otherwise; for him symbolic or representative art, ‘mimesis’, was a lie, an inevitably reductive knock-off which interposes itself between us and the real world. But what kind of conception of the real excludes our only way of conceiving it? William Blake, Alan Moore, all the greats knew that mimicry, make-believe are what make the world. Realists, to round out my pantheon with a Ursula Le Guin quote, of a larger reality. Or in Promethea’s words:

Lindelof swearily swore to make his Watchmen TV show anyway, even getting his writing staff to ritualistically tear up - as a talisman against hexes from Moore? - copies of the comic. Whether Lindelof survived the hex with his 10-hour TV-movie swan-song for Obama I’ll be writing about in a coming post.

Ironically, having wanted to end superhero comics with Watchmen Moore revisited them with Supreme, though going for a Silver and not expected Bronze or even Lead Age take on the story, much like he did with sunny Tom Strong.

Interview with From Hell artist Eddie Campbell for Egomania

The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore by George Khoury

It’s like Tolstoy ending War and Peace with his novelistic essays on history, or the book within a book in Orwell’s 1984. The people who skip these aren’t the authentic story salafists they think but, while being happy to otherwise read reams of hot takes and guff web copy and the backs of cereal boxes, are immune to the possibilities of fiction outside the one of its modes that is narrative.

Alan Moore ends things: it’s part of his thoroughness. Series like The Swamp Thing or Crossed don’t feel worth reading on after he’s done with them. He tried to sum up and put to bed superheroes with Watchmen. He even tried to (again) end/restart the world, and from and to a much darker place, with recent horror series and Lovecraft homage Providence (although calling it a Lovecraft homage is, I dunno, like calling The Book of Revelations an homage to the Book of Daniel. Sole big laugh from the theology major at the back.)

The joke Aleister Crowley tells which has the key to existence is about a man who’s bought a mongoose for his brother. Why? Because his crazy brother sees serpents everywhere.