When Italo Calvino got his destinies crossed

That's bad? / Possibly. The cards are vague and mysterious

The problem of prose: how to generate all that text from the first word to the last, how to fill all that space between front and back covers? Take your average novel length (or depth): imagine having to line up 100,000 words! one after the other! The laboriousness of it, the RSI, the daunting glut of available vocabulary. It’s enough to drive you to a quick fix.

For there are ways to write a book that’s not just taking dictation from your inner monologue, or write novels that don’t involve tracking every utterance and gesture of your characters like you’re their Stasi officer. One way to generate text is through what Lincoln Michel of

calls ‘rev engines’: repeated motifs, simple procedures that help rev your creativity, that restrict choice and so free your imagination. You might, for instance, alternate the concepts of ‘up’ and ‘down’ paragraph by paragraph: as trajectories for your characters, moods, fluctuating fortunes.Another, more esoteric helpmeet is a sort of literary fortune-telling. Writers and artists can generate work, break through blocks, take inspiration from and towards new ideas by drawing upon existing systems of the occult or Eastern tradition. The I Ching and its yarrow-stalk divination helped Philip K Dick and Ursula K Le Guin, the father and mother of modern SF, with their fiction and non-fiction respectively. (Fun fact: Dick and Le Guin went to the same school but never met. Read into that.)

Then there’s the Tarot, that card game turned fortune-teller. As content, its oversized playing cards - with their suits of pentacles, wands, cups, and swords, and Major Arcana like The Tower and The Hanged Man - have featured in art as far wide as The X-Files, The Simpsons and ‘The Waste Land’. T S Eliot took it only half-seriously, admitting in the endnotes to his poem that, “I am not familiar with the exact constitution of the Tarot pack of cards, from which I have obviously departed to suit my own convenience.” Departures like his character Madame Sosotris using cards not found in any Tarot deck when she conducts a reading early in the poem which predicts what else we’ll find in it…

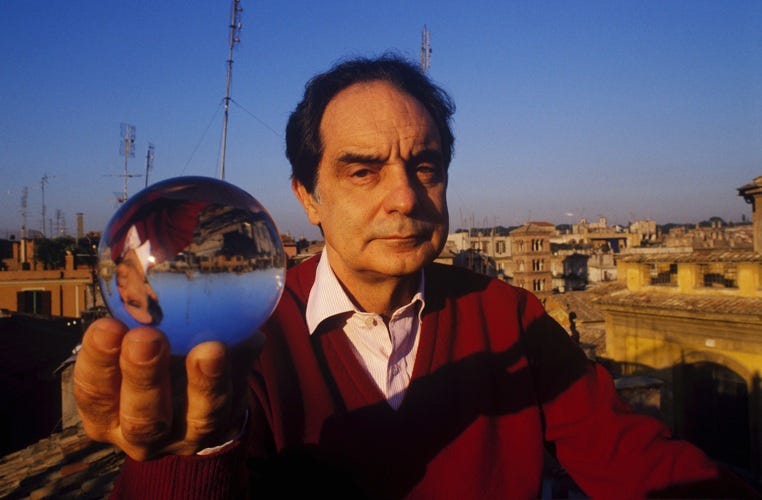

This little self-reflexive touch isn’t any evidence Eliot used the Tarot to help him compose ‘The Waste Land’. For him as for Ezra Pound, the esoteric and archaic were a long-untapped resource to draw upon and reconstitute as part of their modernist project. It would take a post-modernist like Italo Calvino to use the Tarot, intricately and rigorously, not only as content but to generate the form and structure of a work of literature, with his 1973 novel:

Calvino is to some a writer of experimental literature. To me this always implied something provisional or unproved. Calvino was more a literary inventor. His finished results - from the never-ending, never-middling stories of If on a winter’s night a traveller, to the magical mystery tour of Marco Polo and his Invisible Cities - are crafty in the making and delightful in the reading. I wanna try buff some of the original shine back into that worn-down word ‘magical’. Calvino’s literary inventions have the marvellousness and otherworldliness of magic combined with its underlying systems of rules.

Rules must’ve attracted Calvino to the Tarot. In his endnote to the novel he explains how he “realised that the tarots were a machine for constructing stories.” His stories start with travellers taking shelter in a castle where they share tales over ale. So far, so medieval. But they’ve been robbed of speech and so have to use cards from a Tarot deck to storytell to one another. Then in the novel’s second part, another set of travellers uses another Tarot deck to retell and remix famous tales from literature.

Calvino storytold like his characters had to, with the Tarot, laying a grid of cards and reading into them vertically, horizontally, in reverse or intersecting each other, like an elaborate one-man game of Dixit.

For the most part, the Tarot content, form and theme braid together beautifully. Here the narrator uses Tarot cards to remind us of the stories about ephemera, missed chances and might’ve beens which will always dwarf the number of true stories:

“You must ascend to Heaven, Astolpho,” (the angelic Arcanum of The Last Judgment indicated a superhuman ascension) “up to the pale fields of the Moon, where an endless storeroom preserves in phials placed in rows” (as in the Cups card) “the stories that men do not live, the thoughts that knock once at the threshold of awareness and vanish forever, the particles of the possible discarded in the game of combinations, the solutions that could be reached but are never reached…”

Passages like this fill The Castle of Crossed Destinies. But they are passages. In the Tarot, Calvino had found a literature machine that got him to write beautifully. From what overarching vision, though, to what end?

Calvino did not mean to structure his book without its Tarot conceit being visible like rebar in concrete, as he’d done with the numerical patterning he’d used to structure Invisible Cities. He revealed the conceit within the story by having his characters duplicate his storytelling method. But the true ingenuity of the method is hard to discern let alone keep track of. Soon you stop trying to track it and just take each chapter’s tale as it comes.

The method is actually most apparent, and the novel most interesting, in its endnote, where Calvino wrote wittily about his experience using the Tarot to write. It’s telling, though, he had to break it down for the reader. And charming, if worrying, that he confessed to getting maddened and frustrated by his own conceit:

Suddenly, I decided to give up, to drop the whole thing; I turned to something else. It was absurd to waste any more time on an operation whose implicit possibilities I had by now explored completely, an operation that made sense only as a theoretical hypothesis… Some nights I woke up and ran to note a decisive correction, which then led to an endless chain of shifts. On other nights I would go to bed relieved at having found the perfect formula; and the next morning, on waking, I would tear it up.

Alan Moore - more on whom later - once tried to explain Kabbalah to readers of a secular mindset by comparing it to a restricted field for looking at life, which restrictions then squeezed out unexpected insights and solutions for his art. This brings to mind Oulipo: the literary school - wait, that sounds too scholarly for writers who were so playful… literary club, rather - that generated literature through ‘rules of engagement’, like writing a novel without using the letter ‘e’, or relying on chess moves to dictate the paths of characters around an apartment. Is that how Calvino saw the Tarot, as a fun but arbitrary system of rules with which to generate a surprising story?

He did in his endnote conceive of Tarot as firmer believers might, as an access to the collective unconscious, a means to make language “say something it cannot say, something it doesn’t know, and that no one could ever know.” He’d meant to write a third part of the novel, using modern visual material - adverts or comic strips etc - instead of Tarot cards. But he couldn’t think of what really would be “the tarots’ contemporary equivalent as the portrayal of the collective unconscious mind”. The Tarot cards themselves had started out as playing cards, so his suggestion of comic strips wasn’t cheeky or profane. But the playfulness of the suggestion implies a similar attitude to Eliot’s towards the Tarot at large.

When Alan Moore described Kabbalah and its mystic take on the Hebrew alphabet as a finite set of symbols, which by their finitude and particular perspective throw interesting lights on reality, this was his own symbol. He was using a metaphor to try explain his comic-writing methods to a sceptical reader. He himself is a believer. He follows the spirit and not just the letter of magical law. Calvino, fantastical between the covers but materialist on the streets, did not. Writing of French Oulipo writer Raymond Queneau, he made the case for the novelty of Queneau’s and implicitly his own work residing in the laws or rules themselves:

It has to be said that in the ‘Oulipo’ method it is the quality of these rules, their ingenuity and elegance that counts in the first place; if the results, the works obtained in this way, are immediately of equal quality, ingenuity and elegance, so much the better, but whatever the outcome, the resultant work is only one example of the potential which can be achieved only by going through the narrow gateway of these rules. This automatic mechanism through which the text is generated from the rules of the game, is the opposite of the surrealist automatic mechanism which appeals to chance or the unconscious, in other words entrusts the text to influences over which there is no control, and which we can only passively obey. Every example of a text constructed according to precise rules opens up the ‘potential’ multiplicity of all texts which can be virtually written according to these rules, and of all the virtual readings possible of such texts.

Calvino’s bind with The Castle of Crossed Destinies is that he at once “felt that the game had a meaning only if governed by ironclad rules,” but at the same time he relaxed them and “gave up patterns and resumed writing the tales that had already taken shape, not concerning myself with whether or not they could find a place in the network of the others,” all this despite knowing that without the conceit “the whole thing was gratuitous.” He couldn’t capture or didn’t think there was meaning beyond the rules.

He was never then, like Dick and Le Guin, using esoterica as a way of “appealing to chance or the unconscious,” of dowsing his own unconsciousness for ideas which he didn’t know he knew. In his essay, ‘Cybernetics and Ghosts’, collected in the tellingly titled book The Literature Machine, he described writing prose variously as, “simply the process of combination among given elements” and “merely the permutation of a restricted number of elements and functions”. A very front-brained, controlling, rationalist way to go about it. Within The Castle of Crossed Destinies itself the narrator admits:

only tarot number one honestly depicts what I have succeeded in being: a juggler, or conjurer, who arranges on a stand at a fair a certain number of objects and, shifting them, connecting them, interchanging them, achieves a certain number of effects.

But using the Tarot to shift, connect and interchange gives the lie to his method. Literature isn’t just the current total of the virtual possibilities and effects that can be achieved through the recombination of words—take note ChatGPT (more on which in part 2). Randomly albeit algorithmically generating a novel doesn’t guarantee a good or even an interesting one.

Except for the above-mentioned highlights of well-braided pose, the Tarot isn’t intrinsic to any overall vision of The Castle of Crossed Destinies. Calvino could’ve used coin-flipping or tea-leaves or, like Dick and Le Guin, the stalks and hexagons of the I Ching. Instead he got only two out of three things right. First, he featured the Tarot as content in the novel; second, he himself used only the rows, columns and preordained paths around hands of Tarot cards to construct it. The third thing missing was a point beyond patterns. For a writer to use magic-inspired creativity well, with internal cohesion and not just arbitrariness, they have to, maybe not be a full believer, but at least be a make-believer…

Next time, I’ll be looking for a point beyond the pretty patterns with Jessa Crispin, founder of all-timer aughts literary blog Bookslut, author of Why I Am Not a Feminist - a Feminist Manifesto, The Dead Ladies Project, and for my purposes, The Creative Tarot, being as she is the designer with artist Jen May of their own Tarot deck, Spolia. I predict great things for you in reading part 2.