The late great Edmond Caldwell - novelist, critic, scourge of James Wood - wrote twice on his blog (what they used to call a substack) about end of year ‘best of’ lists. The posts were titled List Lust, or, The Banalities, and The Best Dressed Books of 2008, to give you an idea of where he stood.

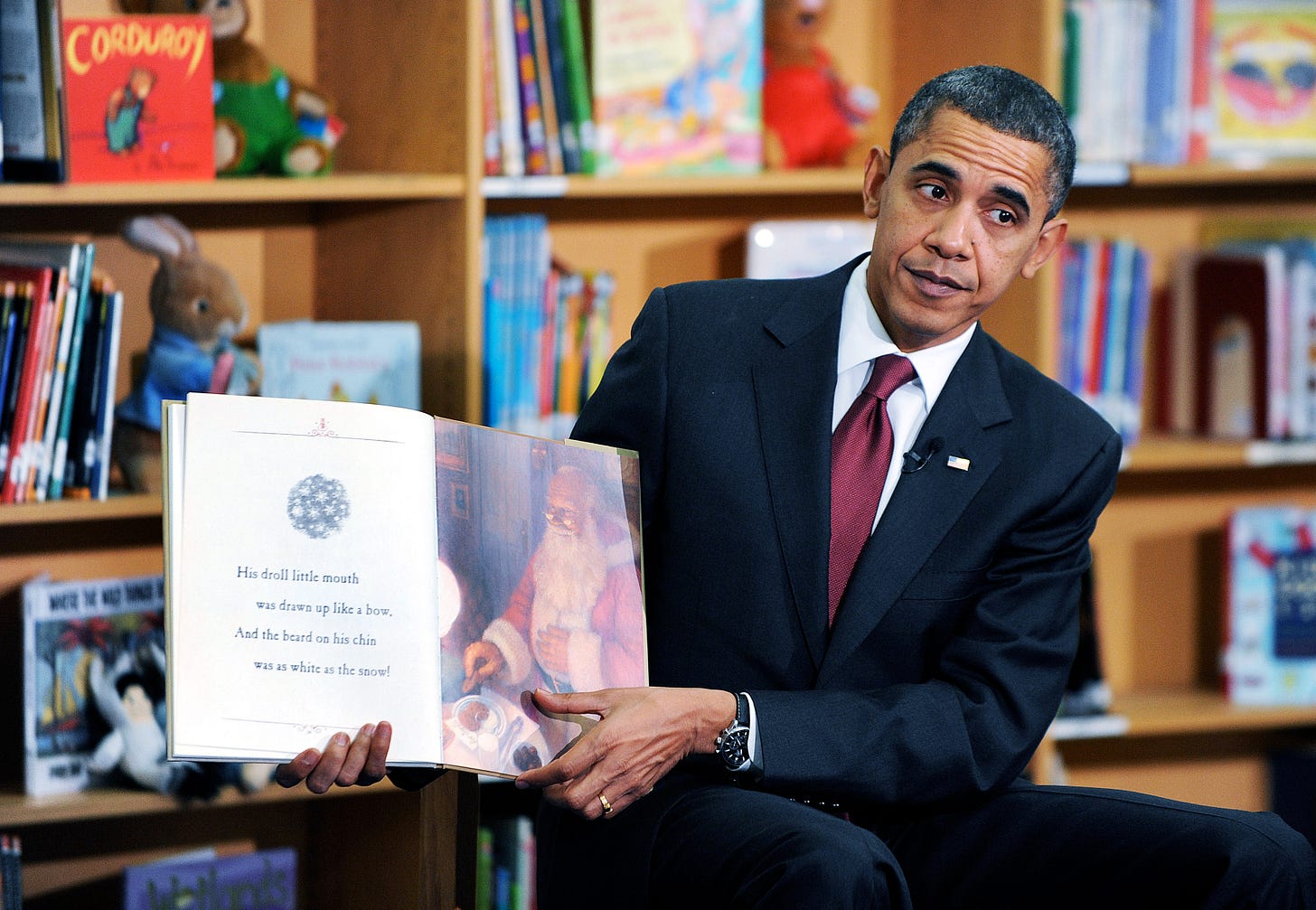

Pointing out such lists are marketing exercises - a way to cash-in on the Christmas gift rush - would these days garner you no more than a resounding “Yes and?” (if words so jaded could actually resound). Say you nevertheless want to avoid writing what are essentially low-key advertorials. One option is to rise to such Obamaesque heights that your best-of lists are more like magnanimous acts of king-making, that you’re able to hire an assistant who’ll colourfully set your lists in Adobe InDesign and post them for you on social media. (What does it say about your best-ofs that even after leaving office they read like they’ve been focus-grouped?) But then I had another idea, a better option to appease Caldwell’s splenetic spirit: releasing a best-of list after Christmas. Then I had a stupider idea. For what’s the opposite of seasonally refreshed hype, of being on-trend?

The best book of 1922

At school I remember weighing up two novels off a shelf with no bearing on which to read first, East of Eden or Ulysses, when I saw my English teacher, Mr. Prestwich. Pert wanker that I was, I asked his recommendation. He said maybe for now I should try the Steinbeck over the Joyce, a tired smirk on his face. Back then I put it down to his dour personality (his nickname among other teachers was Mr. Deprestwich). And I was, at that age, still branching away from novels with explosions on the cover to the weirder world of capital L lit. Over the summer holidays I read East of Eden as a bored receptionist at a hairdressers—platonic ideal setting for a Steinbeck potboiler. It wasn’t till the first year of uni I came round to Ulysses and finally got Mr. Prestwich’s smirk.

If your family background’s not of any great canon-reading pedigree, the names of great works and authors don’t hove into view in any constellations but more like place names seen on a new train journey. You’re surprised to learn this links to that (wait what, Colchester’s next to Ipswich?). And it’s this unfamiliarity that accounts for most of the difficulty of ‘difficult’ art.

The unfamiliarity of Ulysses is its… everything: its verbal registers, its wealth of styles, the subject matter of its parodies, its odd combos of tone with content, its microscopic focus—unfamiliar both to those who first read it in 1922 and to anyone who first reads it with relative naivety. For me aged 19 it was a great example of and precursor to Donald Rumsfeld’s unknown unknowns. I hadn’t even known I didn’t know a book could look like this. Neither studying Dubliners for GCSE, nor frowning my way through a trendily reissued A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (Ewan McGregor blurb on the cover: “An extraordinary novel”) had been enough to familiarise me.

Unfamiliarity needn’t exclude you though; paradoxically it can sometimes be what allows you access. If I was ever going to offer advice, it’d be to read weird books young (watch weird films, listen to weird music young). Not because there’s anything morally improving in doing so. But so that you get in early, before you’ve inherited defence mechanisms that let you off from bothering with such works, before you receive the wisdom for and against.

And if you’re not so young or naive? Well still this isn’t one of those ‘Why you should read Ulysses’ wrong-tree pissings-up. A set-text in English lit courses the world over doesn’t need defenders or apologists. All I can do is sketch why the book was the best of 1922 and, in a way, of any year so far.1

Borges, who’d go on to describe the reception of Finnegans Wake as “terror-stricken praise”, was nonetheless a good reader of Ulysses. He recognised how with it Joyce had proved “a millionaire of voices and styles”; he recognised its innovation: in a world before ‘stream of consciousness’ had been coined, Borges’s attempt at naming the “hitherto unpublished form” was the cuter and more poetic “silent soliloquy.” Ulysses was so innovative it was exhaustive, according to Anthony Burgess—an evolutionary leap without descendants, both new horizon and cul-de-sac: “Ulysses innovated for itself and itself only. It is inimitable.”

One of its innovations was a before-the fact synthesis of what would be two major trends in 20th century literature. Italo Calvino, explaining his affinity with Borges, wrote of recognising in him:

a world constructed and governed by the intellect. This is an idea that goes against the grain of the main run of world literature in this century, which leans instead in the opposite direction, aiming in other words to provide us with the equivalent of the chaotic flow of existence, in language, in the texture of the events narrated, in the exploration of the subconscious. But there is also a tendency in twentieth-century literature… which champions the victory of mental order over the chaos of the world.

Yet Ulysses is both: an equivalent of the chaotic flow of the existence (of a single day) and that same chaos put in intricate mental order. That’s what makes it modernism’s masterpiece.

A word, though, about that order. There’s a way to close-read Ulysses that’s an example of what Milan Kundera called “sophisticated stupidity”. And that’s primarily as a system—all those schemas and tables with each chapter’s dominant organ and colour and Odyssean heading. The latter are fine as a crib for how Joyce constructed each chapter (the later editions don’t have chapter headings) but reading the book to chart its allegorical nods is to miss the best of it (and is hardly the best way to sell it either). Better to think of each chapter - or ‘episode’ - as a different track on a concept album: with its own vision and shtick and flourish Joyce is trying to pull off (he once said his ambition with each chapter was to see if he could get it across the finish line).

Critic Guy Davenport was on a better track when he titled his essay on the book ‘Joyce’s forest of symbols’. (It was eagle-eyed Davenport who noticed how the novel’s famous last word ‘Yes’ is contained in reverse in its first word ‘Stately’ - a level of fine detail that film fans might trivialise as ‘easter eggs’ but is in fact further proof of Joyce’s almost-unfathomable thoroughness; Ulysses’s bit-rate, its level of patterned information, its meaning density must be among the highest in literature). The novel is as organic as a city sprawl, as meticulously engineered as the trees of a forest.

That density is fruit of Joyce’s pre-Babel command of languages. Davenport again:

For Joyce’s skill the critic Hugh Kenner coined the phrase ‘double writing.’ In a sense, all writing and all language is double by nature, for words are all metaphors that have lost their resonance through use. Joyce demands of us that we know the archaic components of words.

Some venerate these demands Joyce makes on the reader. Borges went on to quote Lope de Vega on Góngora as a way to summarise his feelings about Joyce:

I will always esteem and adore the divine genius of this Gentleman, taking from him what I understand with humility and admiring with veneration what I am unable to understand.

Others don’t have time for books that make demands, and find it especially off-putting when a book has its own guidebooks. But these aren’t necessary on first or even second read. (Shakespeare’s a good analogy here. You can get plenty out of a virgin watch of a play, so long as the production’s well staged and acted. But once you’ve read the play, out loud, so the meter stresses the weird syntax into sense, and the meanings of archaic words are to hand in your memory’s glossary, then the play goes from noise to signal, it unblurs.)

Maybe fewer are put off by Ulysses in an age where we listen to director’s commentaries, check IMDb trivia, read oral histories and genius.com footnotes. That it comes with a lit-crit entourage isn’t testament to how demanding it is but how rich: and the riches are there for the taking, if you’re willing to meet, to quote Patricia Lockwood, a little “more than halfway.” Ulysses is a Mandelbrot Zoom: the deeper you go, the more you get.

The key for any close, that is a good reading of Ulysses, is to be as catholic as the book, pun sorta intended: to plumb its depths, marvelling at the levels of order Joyce put into the book, while at the same time appreciating how they constitute its myriad surface-level pleasures: the comedy—highbrow and fart jokes both; the pathos of its humdrum characters—Jewish Leopold Bloom, the gentle cuck, and blowsy Molly Bloom, and even poindexter Stephen Daedalus; the quality of its prose (which was never merely “beautiful”: Davenport again: “Joyce broke out of neoclassical rules while seeming to obey them… he dared to be angular, eccentric, barbaric”). Ulysses’s power is its double-writing in all senses. It’s modern and ancient, suprapersonal and personal, pointy-headed and big-hearted. Taken patiently, in good faith, it is the most literature of literature. Sounds unappealing? But what if someone recommended you a film on the basis it was the most cinematic?…

Best poem of 1922

What was in the water in 1922 that gave us Ulysses and ‘The Waste Land’? (For one their authors were linked: according to Matthew Hollis’s ‘biography of the poem’, T S Eliot gifted poor Joyce a pair of second-hand shoes, only for a humiliated Joyce to spend the rest of the night and his money getting in the drinks.) One thing in the water that’s often pointed out is the ruins of the Great War, though in Peter Ackroyd’s biography of Eliot we learn the man himself didn’t subscribe to any “dissolution of values” theory behind his poem. Then again, in a later one, ‘East Corker’, he seems to explain the modernist project in such terms without naming it so:

So here I am, in the middle way, having had twenty years - Twenty years largely wasted, the years of l’entre deux guerre - Trying to learn to use words, and every attempt Is a wholly new start, and a different kind of failure Because one has only learnt to get the better of words For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate With shabby equipment always deteriorating In the general mess of imprecision of feeling, Undisciplined squads of emotion. And what there is to conquer By strength and submission, has already been discovered Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope To emulate - but there is no competition There is only the fight to recover what has been lost And found and lost again and again: and now under conditions That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss. For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

To recover what has been lost is the epic ambition of Eliot’s pseudo-lyric poem. Like works as far afield as Pound’s ‘The Cantos’ and Alan Moore’s comic Providence, ‘The Waste Land’ is an attempt to reboot a moribund civilisation, to alter the present with the past, repositioning modern English poetry - and Western culture - so that it takes a salutary view of the archaic and Eastern.

More curiously ‘The Waste Land’ is an attempt to alter the past with the present too. In his essay ‘Tradition and Individual Talent’, Eliot wrote:

The existing order is complete before the new work arrives; for order to persist after the supervention of novelty, the whole existing order must be, if ever so slightly, altered; and so the relations, proportions, values of each work of art toward the whole are readjusted; and this is conformity between the old and the new. Whoever has approved this idea of order, of the form of European, of English literature, will not find it preposterous that the past should be altered by the present as much as the present is directed by the past. And the poet who is aware of this will be aware of great difficulties and responsibilities.

‘The Waste Land’ has a reputation of great difficulty, another forbidding and reader-unfriendly text. Rounding out my pretentious teens, it was the first poem since primary school or dirty limericks I tried to learn by heart. Youth may well be the lyrical age but who the hell was I trying to woo with talk of dried tubers and rats’ alleys? (It’s like that scene in Love and Death when Boris is dictating a poem to himself: “I should’ve been a pair of ragged claws, scuttling across the floors of silent seas-” [scraps paper] “Too sentimental!”) The forbidding reputation wasn’t helped by the poem’s untranslated foreign quotations and Eliot’s unexplanatory explanatory endnotes. Neither does it help that advocates of modernist poems sometimes treat them like they’re a sort of arcane magic spell.

Maybe open or shut meanings are besides the point. For poet Mary Karr ‘The Waste Land’: “means only by ricochet, never in direct statement. Meaning in the typical sense wasn’t something [Eliot] was chasing. It was only used [and here she quotes him]:

To satisfy one habit of the reader, to keep his mind diverted and quiet, while the poem does its work upon him, much as the imaginary burglar is always provided with a big piece of nice meat for the house-dog.”

What is the work being done upon you as you read ‘The Waste Land’? One is to make you hear everything. Like Ulysses, ‘The Waste Land’ was a triumphant demonstration of how to do polyphony in a written text: you might be able to hear a hundred voices at once in a choir but how can you read them? Like style-millionaire Joyce, Eliot is most modern when he cuts between overheard chitchat and classical texts, sometimes mid-sentence, or when he impersonates everyone from Tiresias the blind seer to Lil the soldier’s cockney wife. (Among other things, ‘The Waste Land’ is a great London poem—London, “unreal city.” I wonder whether Morrissey had read it before he wrote a seeming paraphrase of ‘The Waste Land’ in his lyric, “London is dead, London is dead, London is dead, London is dead”). Eliot’s even post-modern in the way he encloses or psychically predicts the rest of the poem through its early Tarot reading by fan-fave Madame Sosostris.

Eliot was the fav of many fans. Colonel Kurtz loved to quote him and he joined the Special Forces aged 38! Not that Eliot was without his detractors. H P Lovecraft wrote ‘The Waste Paper’, a painful parody of ‘The Waste Land’ in which he couldn’t help mentioning darkies and Jews. (Partridge voice: “Ah, you daft racist.”) Nabokov, who only got round to Eliot in the ’40s once the gold-dust had settled, slyly under-balled the man by calling him, “Not quite first rate”; what’s more, he had his pedo Humbert Humbert versify like him and then, on top of that, worse pedo Clare Quilty mock him for it. I’m sure an aesthetic puritan like Nabokov took his stance on solely aesthetic grounds; but a man with a Jewish wife and Jewish murdered in-laws could hardly ignore the insidious antisemitism of Eliot or the more flagrant kind of Eliot’s mentor Ezra Pound (Nabokov: “a total fraud”).

Surely some of the animus was down to the achievement accorded Eliot. For better or worse his poem, like Joyce’s book, was a switch point on the rails of literature. William Carlos Williams wrote that it “wiped out our world as if an atom bomb had been dropped upon it”, Mary Karr that, “It came down with an axe swoop.” For critic David Perkins, “The 1890s seemed to have happened for the sole purpose of having Eliot decimate them.” So much for all the destructive imagery; what about the poem’s promised end? It’s a hundred years later: will the waste land ever stop growing? Where is the datta, dyadhvam, damyata of the thunder? When will culture be reborn?

Best films of 1922

While an Anglophile American was trying to irrigate a parched culture with the waters of the Ganges and the holy grail, and an Anglosceptic Irish master of English was running the language back and forth through his transmogrifier, the Germans were having a whole other, if not unrelated, time of it. The annus mirabilis of modernist literature was also the breakout year for German Expressionism.

Before your eyes glaze over at that pair of words, remember that without German Expressionism there wouldn’t be a Batman Returns, AKA the cleverest Batman movie (Christopher Walken’s Max Schreck was named for the actor who played the vampire in Nosferatu). Welles and Hitchcock wouldn’t have made half as striking movies without the stark shadows and stark-raving angles of their German predecessors. What was being expressed in expressionism was the subjective; in this way, it too was modernist: the subjective experience of modern man, maddened by the modern.

And there was plenty of madness ahead. 1922 was the year both of the first of the Dr. Mabuse films and of original vampire movie Nosferatu—the former about gangsters taking over Berlin, and the latter about a finagling foreigner who sucks German blood…

What if Weimar cinema was not a last doomed flowering of broadminded German liberalism snuffed out by the coming Nazi storm à la Cabaret but that storm’s dark herald? Nosferatu’s Count Orlock - with his fangs pushed to the front as rodent teeth, his provenance from Eastern Europe - is easy to decode as a reprise and prototype of more explicit antisemitic travesties.

Maybe too easy. Nosferatu’s co-writer was Henrik Gaalen, the man behind that other German Expressionist classic, The Golem trilogy—which alongside Nosferatu were our first monster movies.

In the only film of the trilogy to survive, The Golem: How He Came into the World, a rabbi predicts disaster for the Jews of Prague. In pre-emptive defence, he fashions from clay a golem, which he animates with an amulet containing a demon. The golem becomes the rabbi’s servant and the Jews’ sentinel. When courtiers of the Holy Roman Emperor laugh at a narration of Jewish history, the roof falls in on them as punishment, only for them to be spared at the last moment by the golem. In gratitude the Emperor reverses his decree expelling Jews from the city.

Record scratch: the golem turns out to be a sort of early, Jewish Godzilla in that the protector becomes destructor (making the golem the ancestor of everything from HAL 9000 to M3GAN). The rampaging golem is only stopped by luck and a child, i.e. by providence, by deus ex machina: a random little girl takes off the golem’s animating amulet and it dies. The darker subtext of Gaalen’s scripts wasn’t coded antisemitism but his golem story’s ironic, if inadvertent, inversion of history to come: no god putting a stop to the real world death machine.

A hundred years later should we be making our lists and checking them for works of similar world-historical relevance? But art only ever gets that in hindsight. That’s why you can safely ignore books on best-of-lists blurbed as So Important. Importance, relevance are accidental, a case of moral luck. For every prescient masterpiece that seems to have cannily read the psycho-social currents of the day there’s another that was way off. G K Chesterton’s The Napoleon of Notting Hill did not presage a world in which knight errantry and medieval combat made a comeback. And on the other hand, if history after 1922 had gone less nightmarishly, would Ulysses, ‘The Waste Land’, the films of German expressionism be less powerful? Art’s great landmarks aren’t hostages to history, they’re built on the bedrock of art’s own past. A thing of best-of is best-of forever.

A shout out to John Self who did the lord’s work in trying to rescue other greats from that stellar year of 1922 that were overshadowed by the big dogs. But aren’t the big dogs overshadowed now too?