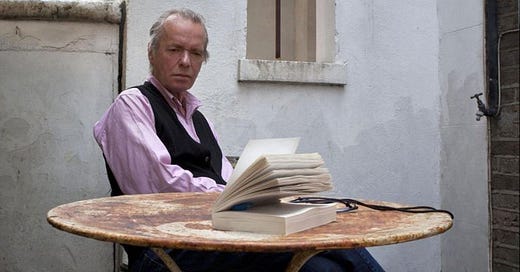

Since the announcement last week of Martin Amis’s death the obituarists have right-clicked through all the synonyms for ‘divisive’. That word, though, ‘synonyms’, feels like a euphemism—for euphemisms. Even the polarity of love-him-or-hate-him doesn’t quite cover it (or I guess now loved-him-or-hated-him). You get the impression that for readers and writers ≤ 40 he was the Jeremy Clarkson of English lit: never mentioned without a strong facial expression. So as not to add to the simplification that where you stood on him ran on generational lines, I suggest a scroll through his low-star reviews on Amazon from the retired ‘I had to read this for book club’ crowd. A fan myself from way back, albeit a tested one, I was left by his death with an urge to pick out the common threads in various people’s animus towards Amis.

thought him an “interesting arsehole” while a friend I texted last week said, “Well he was just a bit of prick”—thus encapsulating both sides of the pelvis and also the idea the problem lay in Amis’s personality. As something of an expert on pricks, I’ve always found this a bit off-the-mark. Four letters off to be exact. Because are we really talking about a personality here? Smarting at someone’s whom you don’t know in person, your problem is with their persona.A persona has three parents. There’s what a famous person does, all the gawped-at ‘private’ life stuff. Amis’s charge-sheet is well known: a who’s-who of love affairs, the teeth-job, his chasing for a bigger advance. The next parent is what the person says in public, such as Amis’s on- and off-the-cuff remarks over the years about euthanasia, children’s literature, Jordan (not the country). There goes Martin Amis again, wading in. And usually coming across as rude.1 It’s almost as if he was on the ‘louche jerk’ spectrum somewhere between AA Gill and Giles Coren. Writing in The Financial Times

even likens him to big-mouth Norman Mailer. In commenter-speak Amis was an above-the-line troll, the kind we’re always told not to feed.Which is part of the point. A persona’s not inflicted on the public, it’s a co-creation between subject, the press and audience. I don’t think Amis especially liked the one he ended up with; in any case he added to it both voluntarily and involuntarily; he was never in total control, his memoir and autofiction notwithstanding. The stories about his life, his reported remarks all came mediated, and in later years, social mediated. (M A Orthofer of The Complete Review pointed out Amis’s controversial remarks timed well with his press rounds for each book. I tend to think he more had a knack for good copy, in a Noel Gallagher way, as opposed to any shit-stirry master plan.)

How we reacted to those remarks, sought them out, how they were framed leads me to the third parent: us, whatever baggage we brought along, what we thought his remarks, deeds and books reflected about him and what we projected onto him. In my case it was one thing - and hardly a surprising one - in particular.

It’s not for his bad review of Anthony Burgess’s 1985 or his low opinion of Gay Talese that Amis got his arsey, prickly reputation. It’s because time and again he did a Bad Politics. With a career that spanned half a century he was publishing long enough to cross the sine wave peaks of ‘the campus wars’ of the early 90s and ‘the problematic wars’ of the late 2000s-2010s (at the very least). It was during the second word war that the accusations of Bad Politics mostly had the inflection of ‘Oh great, Martin Amis has had more thoughts on Islam.’

Two authors he traded words with in that period, academic Terry Eagleton and journalist Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, have written about him since his death: Eagleton not unkindly while Alibhai-Brown reminds us she found Amis “narcissistic and hubristic”2 then adds he once Shiasplained her. Both their pieces chart in fuller detail what a lot of obits mentioned only in passing: Amis’s ‘Age of Horrorism’ three-part potted history of Islamism for The Observer in 2006; then that interview with The Times where he shared his feelings on what to do with the Muslim community after a recently unravelled terrorist plot.

Eagleton’s amplification of the latter led to a huge fall-out with and across the press3; but for me the fall had threatened earlier. I was working a temp job in Piccadilly the summer after returning from abroad where I’d toted around my intros to Amis, the double-whammy of London Fields and The War Against Cliché (both worn from travel and a second read each in less than a year). So when at the end of my lunch hour I passed a newspaper in reception with Martin Amis’s name on the front, I did a spotting-a-friend double-take.

The byline was for a review he’d written of Paul Greengrass’s film about the last plane of 9/11. Halfway through reading, something sounded off. I think it was the phrase, “United 93 begins with the desolate, self-hypnotising drone of early morning prayer”. It sounded like something a travel writer for The Telegraph would complain about on being rudely awoken by muezzins in Istanbul. And so began what felt to a young man like an unexpected and unexpectedly simpatico love affair turning cold.

“No doubt,” Amis wrote towards the end of that summer, “the impulse towards rational inquiry is by now very weak in the rank and file of the Muslim male.” I had some doubts! He wrote about wanting to tell airport security staff to “stick to people who look like they’re from the Middle East” (And what do they look like? Turks? Yemenis? Israelis? / Oh, you know)—this after his daughter had suffered a frisking of her stuffed animal and carry-on rucksack.4 Meanwhile in The Times interview he mood-experimented with such collective punishments for Muslims as “deportation… strip-searching people who look like they’re from the Middle East or from Pakistan... Discriminatory stuff.” As someone who hasn’t been deported (yet; who knows with our recent radical Home Secretaries) but does look like he’s from the Middle East and so has been on the receiving end more often than ‘spot checks’ would let you believe of that discriminatory stuff, my rucksack suspected of worse than stuffed animals - Martin, it was carrying your books! - this all felt a bit personal.

What do you do when a favourite writer seems to have singled you out, given you a sharp little poke in your narcissism, a kick in the egonads? I did what anyone would in that scenario: rigged up a sniffy scorn for him in retaliation, and at the same time fantasised about how to prove myself not like the other girls, to prove him wrong.

I could lurk around Primrose Hill till I found a chance to pass him in the street while reading Critique of Pure Reason, nodding, smirking, occasionally adding, “Kant, you dog, you’ve done it again!” Or go to Amis’s next book launch in full beard and a bloodshot glare then, during the Q&A, thrust my hand up but only to ask if anyone had seen my completed Rubik’s cube. Send him fan-mail with pics enclosed of me posing like Rodin’s The Thinker.

This stuff was fanciful, but the scorn part wasn’t—wasn’t purely retaliatory.

Amis collected his dispatches from the backlines of the War on Terror in The Second Plane. The book is the inverse of his short story collection Einstein’s Monsters, in that the latter comprises mainly fiction with a contextual essay on a topical anxiety, in this case nuclear war, while The Second Plane comprises among the essays just two short stories and the ghost of a longer piece of fiction: his ‘Age of Horrorism’ piece (retitled ‘Terror and Boredom: the Dependent Mind’) which he confessed had risen from the ashes of The Unknown Known, a balked-at satire on Islamist terrorism. Of the fiction that survived, one story was about torture Saddam-style and was published around the year anniversary of the Fallujah massacre. (Amis didn’t endorse the Iraq War, not because it was wrong, chiefly, but because it was “the wrong war”. The right war would be with another country that starts with ‘Ir’ (clue: not Ireland.)) The second story concerned main-face-of-9/11 Mohammed Atta and involved, as Chris Morris sniped, “pretending the hijacker was constipated for six months - brilliantly smuggling into our subconscious the idea that Atta was ‘full of shit.’5

With the proportions reversed between fiction and non-fiction The Second Plane gave us more direct access to Amis’s muscularly liberal takes, such as a just-asking-questions review of Mark Steyn, one of the period’s brown-peril demography-botherers.6 And a piece that imagined Ayatollah Ali Khamenei toddling across the border with a suicide H-bomb under his vest. If anything, the book is a salutary reminder of just how feverish the 2000s were.

In its introduction Amis remained combative despite having recanted his divulged bad vibes to The Times. Self-combative even. He told himself off for previous outbursts of “respect” and “rationalist naïveté” in trying to understand Islamist terrorism, something he now declared led inevitably to “moral equivalence.”

I’ve always thought the polysemy of ‘understand’ to mean both comprehend and sympathise (and of ‘rationalise’ to mean both think about and excuse) was a huge but repressed part of the problem with one of the more annoying debate tropes of those days. Amis was at pains to say in the book he was no geopolitical expert but terrorism remained in his wheelhouse inasmuch as it was down to masculinity. Isn’t that a rationalisation as well, him applying his reason in search of the reasons for political violence?

Sadly The Second Plane shows Amis was a sucker, like so many around him, for what cooler heads had tried insisting was an obfuscation of an essentially regional paramilitary conflict - with some spectacular exceptions - and not the centrifugal existential menace that required all those macho ‘time to pick a side’ op-eds. (A pugnacity that ought’ve made us see muscular liberalism was always more a stung attempt to remasculate liberalism.) Don’t believe it? Then tell me, when’s the last time you, an average non-racist, felt dread about Islamism? Funny that. Did the Islamists all up and disappear? Oh shit is there peace in the Middle East?! Or have we all just been elbow-pulled into the next room for us to piss our public intellectual pants in? Gone the Islamist interregnum and back to The good ol’ Cold War.

In the end what caught in the craw with Amis’s writing on politics for his last two decades wasn’t that he was guilty of some bad-think but complacency: a failure of curiosity (its own kind of anti-rationalism). He did make sure to read around topics he wrote about - his essays and his late novels’ afterwords were ballasted with academic references - but only within a narrow, ultra-dig range: too many of the right books. Take his unabashed admission of a daily news diet comprising the Tweedledum-and-dee pair of David Brooks and Thomas Friedman. Or his redneck anthropology of the Trump fiasco, in which he got all Mencken in blaming not the American establishment but the American public’s cyclic boosting of hucksters, as well as the darned internet. Or his fogeyism and credulous purchase of the narrative on Corbyn’s moment in the burning Sun. For all their diligent erudition, these piece were what the kids call basic.7

Because if you wanted to read someone snarking at anti-war activists (“an incensed but microscopic goblin”) or fretting about the number of babies called Muhammad (“Steyn is a great sayer of the unsayable”) you didn’t need the nation’s leading prose-stylist but could find the same views on your dodgy auntie’s Facebook page, if with fewer adverbs and neologisms. Amis, for a writer determined never to be cliché, had gone fatally unoriginal. How could someone who reviled smug complacency be so complacent about his own? His was a consensus contrarianism; establishment free-thinking. The sort that led Christopher Hitchens to defend as much needed ventilation views that just so happened to align with the US State Department. It all gave you a pang of ‘Hey, remember when you used to be funny?’ which implies ‘used to be thoughtful’. It left you wondering how to—ah, you know what, who cares?

Max Liu for the Independent uses a favourite Amis adjective/adverb (which he himself used in ironic exasperation) when calling the author’s bitter remarks to The Times “unforgivable”.8 These days I wish there’d been a Muslim John Barnes figure around to say what the footballer did about Liam Neeson’s own ‘urge’ confession: Well at least he’s admitting it.

A couple of years ago BookForum (RIP) asked its writers what they wanted to see more from novelists, and one said a white author who was as honest about their race issues as Philip Roth was as a male author about his issues with women and sex. Isn’t that preferable to a cultural establishment that hides its ambivalence behind tactically tolerant smiles?

If you must know, the BookForum writer was non-white; for some of us, keeping this stuff out in the light is a matter of self-preservation. The difficult case of Martin Amis teaches us the poison, could act as a vaccine. “What is damaged and wounding and reactionary in him,” as Pankaj Mishra and Nikil Saval wrote of V S Naipaul, “is essential, a critical part of the work, not something ancillary or disfiguring.”

But even this smacks of caring too much about the wrong thing; another kind of misalignment towards an artist’s sayings and doings over their art, a re-instrumentalisation. Amis’s controversies strike me now as a PR version of quantum entanglement: his comments and commentary didn’t so much unpredictably cause offence as they were a priori offensive within a media economy that lives on as much: provocation and reaction the same. We all get riled by famous strangers sometimes, even ‘hate’ them—but it’s good to keep in mind your hate was anticipated and someone is making a buck off it; to never forget that, for all their fame, they are, and almost certainly will stay, strangers. And so fixating on their bad takes and rude rep is little more than a genteel version of ‘We don’t mix with that village, mum says they’re witches.’

What about the people who hated Martin Amis as an artist though? For his art? And it was hate, it was rarely cool disdain: for every reader that purred at his prose there was another whose eyes and nostrils flared.

For them, as Frank Kermode wrote for The Atlantic:

[Amis’s] public shadow comes between reader and book like a cataract. Reviewers who resent this intrusion (and Amis certainly has enemies) tend to ignore his virtues, which are those of intelligence and style. These would be readily perceived (in his writing, not in newspaper reports) by some ideally unclouded eye.9

Amis wrote on politics; it’s not inappropriate to critique his own as can be plausibly filleted out of such writing. Fiction on the other hand, art, symptomatic of politics as it may well be, is not primarily formed by politics, and so critique of it has to discriminate between the more proximate (and therefore more relevant) causes and the less, has to strive for Kermode’s unclouded eye even though it’s impossible. As Pauline Kael wrote, “You can judge the man by the films but not the films by the man.”

Let’s say even with your eyes reasonably unclouded you still think Martin Amis was a bad novelist, that his laurels this past week have been mere literary establishment groupthink. Such criticism comes at his prose from both sides: it was meretricious, vain, flashy, empty, not substantial enough for those who like their books to feel Important. And at the same time, and what’s worse, Amis was arch and grandiloquent whenever he did leave his comfort zone of trash culture and loutish men for Important issues which were beyond his station and intellect.

To start with the meretricious. Part of the problem was that Amis’s style fell, in the 21st century, out of fashion.10 Roisin O’Connor in the Independent quotes Germaine Greer describing the way his books “went a bit wrong. There was magical realism, restless surface glitter in the prose. It became exhausting and tedious and irritating.”11

What is surface glitter? And is its opposite plain prose? Can plain prose be exhausting, tedious and irritating too? And is it not on the surface? Greer’s dichotomy of surface and depth seems like another iteration of style versus substance, form over content. Something easily but apparently needing to be regularly refuted by asking: what does content without form look like, or substance without a style?

It’s thinking in that impossible binary that leads people to conceive of art with what I call the Magic Eye Poster fallacy. ‘If only it wasn’t for all that convoluted scramble I’d be able to see the dolphin!’ If only it wasn’t for Martin Amis’s words I’d be able to enjoy his books. But the scramble is how you see the dolphin. Style isn’t gloss, it’s an attitude towards the world. It’s how the writer conceives of the world, the wave of their mind, to quote Virginia Woolf.

Her notion of waves reminds us style has something in common with rhythm, with music. Sam Leith’s tribute to Martin Amis is right to describe his best writing as when he was “on song”—but, as such, you can immediately, wincingly tell the moment it goes off-key; nobody can ignore even a slightly out-of-tune tune. (Whereas with your more autopilot-prose you have to dig further into it to expose the fault.) Style suffers from what Amis, quoting T S Eliot, referred to as “the natural sin of language”: its tendency to escape artful control, drift out to sea.

Amis’s language certainly had its choppy moments. Ever since his refined drawl of an English accent became well-known it’s been hard to stifle in your head when reading those novels of his narrated by inner-city Americans. In the novels especially, he could be a point-labourer; he played jokes on every string till the whole lot felt lax (I’m looking at you He Zhizhen from Yellow Dog). He (that is Amis) scorned elegant variation and valued repetition to a fault. John Updike wrote of the novella Night Train12:

[Its] style evinces the simple faith that repeating something magically deepens it. E.g.: “I’m sorry. I’m sorry, I’m sorry”; “She’d always leave you with something. Jennifer would always leave you with something”; “But I cannot get the good guys. I just cannot get the good guys”; “But the seeing—the seeing, the seeing—was no good at all.” But the trouble—my trouble, the reviewer’s trouble—with Night Train isn’t the faux-demotic mannerisms.

Updike was referring to the novella’s cod-gumshoe prose but in any case a good summary criticism of Amis’s prose would be “faux-demotic mannerism.” I think it’s useful, then, to apply here critic Michael Wood’s distinction between style and signature. The former is less self-conscious, more impersonal, yet subtly more idiosyncratic and hence more valuable; the latter is more like the author’s ‘tell’, what can and does easily get accused of mannerism.

Amis’s tell was so pronounced - try contrasting him with verbally thorough authors whose various novels you mightn’t guess were written by the same person, Flaubert for example - that he was always going to start one day, one book, reading like self-parody. And he was easy to parody; Chris Morris lampooned him for coining such War on Terror portmanteaus as “edificide” and “apocollapse”, and lampooned his high style in general: his and Armando Iannucci’s War on Terror satire begins: “The planes strike - as Martin Amis memorably describes them - ‘sleeking in like harsh metal ducklings’.”13

But what if this is like parodying someone’s handwriting? Could Amis do anything about it, other than try not to write like himself? One defence of a writer’s style is to claim it’s as hard to separate from them as their personality. Critic Guy Davenport wrote that:

goes further down the enigmatic line to venture that style is “less something people do and more something that happens to them”, writing of Nietzsche that it’s:I am not aware of having a style (hence my claim to primitiveness), but I am intensely aware of style when I write… Style, “the man”, remains unexplained, like different handwritings. It is imitation that has progressed into individuality; it is a psychological symptom akin to tone of voice and personality; it is a skill, an extension of character, an attitude towards the world, an enigma.

[h]ard to imagine that [he] landed on his particular style out of choice. His writing is arrogant, brilliant, and saturated with a total lack of self-awareness—strangely vulnerable, even in its grandest moments, so over the top and so easy to mock—and Nietzsche the man was all of those things too. (If he’d tried to write in the precise, deliberative mode of a David Hume, he simply wouldn’t have been able to do it.) When Nietzsche describes his own creative process, it sounds less like a craft and more like an earthquake, or a flash flood.

Still I think this slightly mists and dusts any critique of Amis’s art, and of art in general. The problem is the word ‘style’ with its connotations of stylishness, which abets the charges of surface glitter, flashiness, of that most gear-grinding of British sins: showing off.14 But style isn’t couture, it’s structure.

Even Amis’s biggest fans do him a disservice in their focus on his prose. Take Nicholas Lezard for the Guardian, assuring us “famously, Amis’s novels have not much else but prose. Very good prose it is, too - but this can give them too much room to manoeuvre.” Or Kevin Power for The Irish Times: “You read him for his turns of phrase. What is literature made of if not turns of phrase?”

Au con-fucking-traire; literature is made of so much more! That’s why in place of ‘style’ I’d use the more intuitively inseparable concept of ‘form’. Form accounts for how writers of such lucid, traditionally well-crafted and reader-friendly sentences as Alasdair Gray and Ursula K Le Guin were still formalists: artists manifestly aware of, taken by, playful with form. Phrase-by-phrase, you might write what Le Guin called “vanilla English” but still be writing inventive books: inventive at the level of plot or character or narrative transitions or genre conventions; at the paragraph or chapter rather than phrase level; via typography, textual interpolations, polyphony etc., etc. (This article, and especially the debate in the comments, is a great primer for such a distinction15.) And thinking in terms of form wards back as well the Romantic equation of voice, style and individuality.

That equation of style with the individual, the emphasis on a writer’s signature turns of phrase at the expense, or ignorance, of everything else in their work, not only lacks requisite thoroughness from a critical perspective, but it leaves Amis’s fiction vulnerable to critics for whom his turns of phrase just rubbed them up the wrong way. People who like writing (and therefore tend to think in writers) and not books or stories per se are then harder to persuade of his inventiveness as a novelist.

Time’s Arrow is a difficult case in point. A novel about Tod T Friendly, an absconded Nazi doctor, it tells his story backwards. You can see why readers thought this was just a gimmick to let Amis show off with descriptions of things like Tod’s drunken vomiting in reverse:

[W]e knelt before the altar of the can — and pulled the handle. The bowl filled with its terrible surprises… Now we solaced our brow on the porcelain, and emitted a few sour gasps of disgust.

Even Updike confessed he couldn’t fathom who the narrator in Tod’s head is meant to be (note the recursive middle T in Tod’s full name) or the point of the novel’s backwards device. (The device wasn’t even original, said many, lifted from Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse 5!—an odd complaint since, going by Amis’s afterword, it was an open homage.) To understand its point, you have to consider not turns of phrase but of form.

Amis had wondered whether strict adherence to verisimilitude, the “tragic curtsy” of an executed woman, was how Spielberg gave himself permission to make Schindler’s List. What Time’s Arrow suggests is that he himself was averse to depicting the Holocaust with straight sober realism, as if such would be profane by its very sobriety. Only through irony - a structural, strictly moral irony - could Amis tell a Holocaust story, that is tell it in reverse (irony is a reversal), and so put the real horror off-page and in our heads: the redacted obverse of the apparent text. In this way he avoided besmirching the Holocaust by using the familiar devices of even a best-will-in-the-world traditional linear lit-fic novel to pull at our heartstrings (and you don’t have to go far to take his point: read The Boy in the Striped PJ’s). And at the same time, by giving the reader such images as clouds of ash coalescing into Jews, he didn’t pervert history but refreshed its horror, made us see and not just frictionlessly recognise it.

(His second Holocaust novel, so-miscalled ‘Auschwitz workplace comedy’ The Zone of Interest, didn’t find a German publisher for being “irreverent.” But the real problem was that its hilarious horrible bourgeois buffoon Commandant Doll was only a third of the novel beside lovestruck Officer Thomsen and Sonderkommando Szmul. They came from a different, more traditionally reverent world—the sort most critics would demand and approve. And so their thirds of the novel didn’t rise above the clichés of historical fiction. Hopefully Jonathan Glazer’s film adaptation, premiered the day Amis died, found a harmony he himself missed.)16

So much for the meretricious. What about the grasps at substance?

Amis would often talk about writing in terms of the pleasure principle. For many readers and critics this was his problem. To the pedagogical Puritan, something can’t be only enjoyed, it has to be learnt from—a cookie, fine, but with a chit of useful wisdom inside. Continuing the Greer quote: “It’s very hard to watch clever boys showing off because all the time there’s a different kind of writer, writing perfect stories.”

This clever boy tried becoming a different kind of writer; he had “a hunger to be serious” (Kermode again). In the second half of his career he quit the riffs on wanking and dead babies (well, almost; the climax of Lionel Abso hangs on whether a baby might die). It’s as though he’d edged out from one grand shadow only to go into another: Nabokov had been the house spirit of his prose-as-pleasure years; now the plurally curious Saul Bellow was his go-to ideas guy.

Amis’s USP had once been that he used a high style on low topics. This put off the more po-faced—why wax lyrical like he did in Money about “clothes made of monosodium glutamate and hexachlorophene… food made of polyester, rayon and lurex”? But how would things go when he used the high style on higher topics than clothes or food, or booze and cigs and drugs?

The lofty cosmological ennui of Night Train was welcomed by some - see Janis Freedman (wife of) Bellow’s admiring review - and scorned by others as pretentious - see Updike. There was another historical novel, House of Meetings, this time about the gulag, and free of trickery or lacking it, depending on your point of view; then the sexual revolution post-mortem of The Pregnant Widow, with its sheesh return of the Islam question in an unexpectedly taking-the-veil female character. As for career-fulcrum-novel Yellow Dog, Walter Kirn wrote in The New York Times, “The problem is Amis’s intellectualism, which sticks out like a parson at an orgy and shrinks and shrivels whatever it goes near.”

So much for boner-shrinking ideas; what about emotions? Substance means, as well as intellectual heights, a depth of feeling. A father of young daughters at the time of his shift to seriousness, Amis pursued that character dynamic: Samson Young, the surrogate father to maltreated little Kim in London Fields; the Russian narrator addressing his black step-daughter in House of Meetings. An editorial at Pop Matters summed up the critical response:

I’ve heard [Amis] called overly clever by some who want him to continually replicate those darkly funny alienated creatures of his youth, but I’ve also read suggestions that he loses it when confronted with children and becomes sentimental and ridiculous.17 Damned for being too smart by those who want feeling, he gets blasted by those who can’t bear it.

Since novels and short stories are more artificial in the older sense of the word, more well-worked, they emphasise a writer’s tics. Amis in his journalism, as spry as it was, didn’t have the word count or editorial sufferance for passages like the opening one from Yellow Dog:

But I go to Hollywood but I go to hospital, but you are first but you are last, but he is tall but she is small, but you stay up but we go down, but we are rich but we are poor, but they find peace but they find…

Detached from his high style for the most part, his essays, whether on ecological disaster or John Travolta, risked less pretension. So the safest way to like, if you must, Martin Amis was to stick to the essays and journalism, as many maintain to this day (see also David Foster Wallace)—‘many’ here meaning journalists. I counted four at least in their memorials to Amis pat his fiction on the head while joining in the championing of his non-fiction.18 It’s now a cliché to say you preferred The War Against Cliché.

The non-fiction wasn’t a haven from all criticism. There was the above-mentioned The Second Plane, and the stale Stalinism-scolding of his semi-memoir Koba the Dread, which provoked Christopher Hitchens of all people to tell Amis not to be silly. But for the most part, the essay collections, running from The Moronic Inferno to The Rub of Time (trust the author of many a drug scene to name his last collection after a euphemism for trying to wank on coke) are, it must be said, easier to like Amis in. His long-reads on porn stars, on the murder of black kids in Atlanta, the AIDS pandemic, give an impression of, in the best sense, a well-meaning liberal, an early, humane commentator on gender, race and sexuality. And on the other end of likability, he was funniest, and his cruel humour was most palatable, when he was practising lit-crit, that is criticising literature. One of my favourite passages, from the memoir Experience, relates a drunken scene when he “settled down for a concerted goad and wheedle” of

for liking Samuel Beckett. They almost threw punches. (“By this stage Salman looked like a falcon staring through a venetian blind.”) And if you needed proof that book reviews can be a minor art, there’s the vicious fun of his ever-re-readable ‘Bob Sneed broke the silence’—that Lizzy Borden of a hatchet job on Thomas Harris’s Hannibal, as well as Amis’s revenge on the UK press by spitting venom on hacks turned casual blurbers of books (Mark Lawson never reviewed one in public again).Yet a minor art it remains. For Amis’s best synthesis of big ideas and feelings with turns of phrase and inventiveness of form, for his best example of how a writer is more deliberate, careful, judicious and moving, and more pleasing, in the gradual accretion of a book than they could ever hope to be in any discrete, discreet moment of their life, you don’t have to stick to the non-fiction at all. You can just go to:

Read the next part to find out why.

For what it’s worth he also made plenty of nice remarks; I remember in particular his fatherly review of Nick Frost’s John Self in the TV movie adaptation of Money.

Amis seemed hurt when Charlie Rose brought up a remark of an unnamed friend that he’d been voted least likely to say, ‘And how are things with you?’

The columns that sprang up in reaction did overshadow the interview’s amusing and now poignant image of Amis being terrorised in Uruguay about his smoking by his young daughters.

One of their lesser known comedies.

Chris Morris’s beef with Martin Amis in person and in print did lead to the former “biting his tongue and channelling it through a piece of work”: the at-first nonplussing but now classic film Four Lions, which proved you can satirise terrorism like Amis’s aborted novel had shrunk from, can explore the mind of a terrorist with more insight than other premature artistic responses to 9/11 like Updike’s Terrorist (Updike’s Terrorist would’ve been a better title).

If you wanna know why the ‘Islam isn’t a race!’ comeback falls on such deaf ears and raises so many eyebrows, look at how credulously, with what alacrity, secular liberals bought into the idea of ‘Muslim babies’, more so than even Richard Dawkins’s most fundamentalist opponents.

Hitchens wrote in one of his more eye-rolling Slate.com ‘Fighting Talk’ columns that certain political truths and principles just are banal. He really was the contrarian’s contrarian, the sort who boldly risks the idea ‘What if things aren’t a bit more complicated than that?’ Another defensive rationalisation to round out a last decade of epicyclic rationalisations.

Amis on Lolita: “In common with its narrator, it is both irresistible and unforgivable.”

The quote continues however, “Of course, Amis has helped in the construction of that public shadow, and if even the well-disposed reviewer cannot quite banish it from his sight of the book, the fault is partly Amis’s own.”

Fashions go and come. Cyril Connolly famously described the pendulum swings in prose between the mandarin and the journalese styles. Pom-pomed slippers and tasselled cuffs will return; Richard Seymour - no mean wordsmith himself, no nor Amis fan too - heralded said return better than I ever could with his moving, stirring, rousing piece for Salvage magazine, Caedmon’s Dream (which begins with the Angela Carter quote, “Okay, I write overblown, purple, self-indulgent prose. So fucking what?”)

In an era where websites seal articles with Conflict of Interest statements, I do think it’s telling that the Independent omitted how Amis and Greer were ash to each other, i.e. ex-flames.

Here’s a good literary pub quiz question: What connects this novella and Back to the Future? Oscar Peterson’s ‘Night Train’.

I think ‘edificide’ is actually quite good. The point of the 9/11 attacks was only secondarily to murder as many people as possible. The real point was the symbolic and actual destruction of symbolic and actual examples of US power: financial, military—and, had the fourth plane hit its rumoured target of the Capitol building or The White House, political. Which explains how, controlling for the averted loss of greater life, and not ignoring those murdered on/by flight United 93, the final disaster on 9/11 was strangely anticlimactic, a relief of a dud: the aesthetic failure of the day’s snuff-performance art.

It goes without saying style doesn’t have to be flashy; look at Beckett, as easily identifiable from a single sentence for its grit as Amis was for his glitter.

The OP, A D Jameson has a great insight that the penchant for tough, chewy, word-by-word-arresting prose is not necessarily a refined desire for complexity but for instant gratification. Plainer prose might be more boring (and I write as someone who, getting his pop-fill from movies and TV, can’t abide any prose too under-seasoned) but its complexity may well just lie at a further level of remove.

Not only did Amis die the day his first good film adaptation (by all accounts) premiered, but at the same age his father, Kingsley Amis, died—a neat joke from the universe about the two authors’ inseparability in some critics’ eyes. And he died of the same cancer as his best friend Christopher Hitchens. At this rate I await more novelish coincidences. Died in the same Florida town where Nabokov caught a rare butterfly! On the centenary of when Bellow met his inspiration for Humboldt!

Xan Meo’s head-injured predatory relationship in Yellow Dog with his infant daughter can be read as a fuck-you to all this.

I hope he, after some blushing, would’ve found the journalists’ kindly consensus a bit rich. He once called them out as jealous rivals at writing long-form prose, and suggested they trashed his novels because they didn’t like a style that “made them feel stupid.” Sick burn.