When I hear the word ‘gun’ I reach for my culture

Left and right fight over realism in the arts without knowing what it is

Once during a panel at a literary festival I heard an experimental poet’s take that “realism is the language of fascism.” In the words of the rich kid on Christmas morning, there’s a lot to unpack here.

To start with, there’s the take’s smug obverse. Say you were told acoustic guitars were the music of fascism by someone who plays electric guitar; you might think their statement was a bit self-aggrandising. If the artistic modes you don’t work in are fascist then your own artwork by implication is anti-fascist (or at least neutral, though I suspect the poet didn’t think of their work as such but out there on the front-lines, fighting the good fight, one free verse at a time).1

Have I got the wrong end of the poet’s logic though? Saying, “Cricket is the sport of Pakistanis” doesn’t mean to say cricket is Pakistani. The poet hadn’t claimed all fascist art is realist but that realism (implicitly realism in the arts) is the way - or at least one of the ways, and one significant enough to be called the language - that fascism expresses itself: that fascism speaks realism.

Even before we stress-test the logic, the premise could do with a shake. In other words: is realism the language of fascism? Historically was fascist art conceived of and taken as realist?

Let’s ask a Nazi. Here’s Professor Winfried Wendland, writing about ‘Nationalsozialistische Kulturpolitik’ in regards to the Great German Art Exhibitions of 1933:

People are coming to their senses. In art they call for simplicity, honesty, and directness. We have overcome Impressionism, Expressionism… and we have attained clear images.2

Art that’s simple, honest, direct, clear—well this sounds like it’d map onto the modern vernacular conception of ‘realism’, not least with its implied hostile contrast to art as ornamented, tricksy, ironic, obscure. But the art admired by Herr Professor actually scorned representing everyday German life, as endorsed by another Nazi, Baldur von Sirach:

God forbid that we should succumb to a new materialism in art and imagine that if we want to arrive at the truth, all we need is to mirror reality… The artist who thinks he should paint for his own time has misunderstood the Führer. Everything this nation undertakes is done under the sign of eternity.

Which means art that’s idealistic if not full-blown mythopoeic. Like that of Leni Riefenstahl, who said, “What is purely realistic, slice of life, what is average, quotidian doesn’t interest me.” As well as starring in a number of Wagnerian mountaineering dramas (of which Hitler was a fan) Riefenstahl directed two of her own, The Blue Light and Lowland. These films were mythic over prosaic, elitist over democratic, supernatural over natural, and - stylistically - as far removed from realist films of the 1930s like La Grande Illusion as something like Solaris is from The Right Stuff. “The Nazi films are epics,” wrote Susan Sontag: “in which everyday reality is transcended.”3

At the same time, how does the notion that realism is the language of fascism square the existence of anti-fascist realist art on the one hand and on the other, saluting hand fascist non-realist art?

Enough realist art and artists of the ’30s - Steinbeck, Dos Passos’s U.S.A. Trilogy - bristled with pro-left or anti-fascist themes to acquit the mode from complacency or complicity4 (as did non-realist art like the schlocky movies Black Legion and Confessions of a Nazi Spy and SF novels like Swastika Night). Even discounting art made as propaganda, there were novels like Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, whose democratic polyphonic form and humdrum milieu were by their nature anti-fascist even if the novel had no point to make (other than families suck). Whereas plenty non-realist artists circa 20th century fascism cross-pollinated with it to tarnish their record: see Ezra Pound’s primitivist-modernism (good metonym for fascism, that); or futurism, an aesthetic not of the world as it is but what it should be: massive, of the masses, mechanical, violently dynamic. Yet too many critics still act, as I wrote on Denis Villeneuve, “as if there’s never been subversive realism or a complacent avant-garde.”

The above examples might be the exceptions to the rule. What’s the rule, though, what’s this fascism whose language realism is? Not the historically sound definition, mind. The definition the poet wants to be true. It has something to do with ISAs.

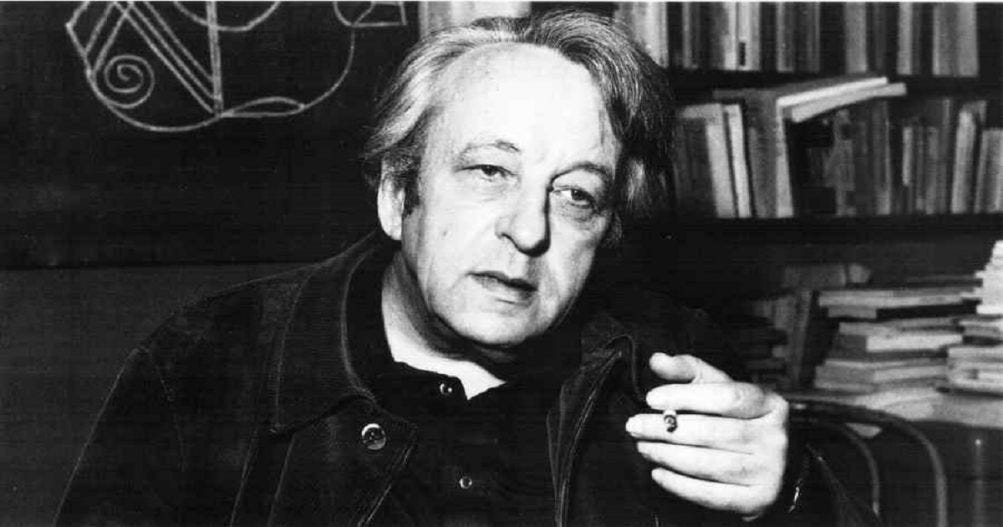

Not the UK government’s tax-free independent savings account, but the ‘Ideological State Apparatus’ as coined by Althusser. It’s the system of institutions - media, religious, family, legal, political, educational and, for our purposes, artistic - that abet the more in-your-face violent apparatus of the repressive state (the police, army and so on). It does this through ideology, materialised in the social and linguistic rituals and practices it ingrains in us and governs us with. (Call it the Deep Status-quo.5)

What do we call our current political state of affairs, this patina of liberal democracy AKA demagoguery with human-values, corporate-commanded economy, digital surveillance overseeing mass hysteria, tooled-up police standing by spree killings, a general terror of and schadenfreude in violence? The only sane answer is ‘Who knows?’ but for some an easier short-hand is ‘fascism’ (it’s in that sense the royal family is fash, cupcakes are fash).

Following the presumption that we are in fascism is another: that the aim of realism is to ‘accurately represent reality’, to confirm, in Althusser’s words, “that everything really is so”. But in representing, i.e. regurgitating reality instead of subverting it, realism performs its ideological function of affirming that “everything will be all right: Amen – ‘So be it’.” (Call it status-quotation.) Even if on the content-level a realist work were some impassioned piece of political satire against our terrible state of affairs, its form would reinforce that state through its conventionality, its repression of the imaginative or irrational or surreal, its aesthetic good behaviour. Hence: “realism is the language of fascism.”

Which brings us to the real core conflict, the bullshit binary, one that recurs throughout 20th and 21st century art histories: realist versus experimental art as presumed to mirror complicity with the political status quo versus the subversion of it.6 If realism stands for the extant, the world as given (‘So be it’) then non-realism, (mis)understood as consonant with experimental art, must stand for difference, possibility, change, freedom.7

An immediate snag to this framing is that anti-fascist politics and experimental art haven’t been consonant all that often. Socialist Realism meant art that was proletarian in subject matter, typical in the scenes it represented and realistic in how they were (although it also had to be partisan, hence why it wasn’t realism as we’d perceive it today, instead being the communist equivalent of Norman Rockwell paintings). Be that as it may Socialist Realism formed in opposition to futurism and other avant-garde art movements, whose turn it was to get trashed as bourgeois, decadent, capitalism’s maidservant (during that Soviet-wide pullback on the artistic foment of the 1920s).

A more regular snag is the way fascist art - whether it was anti-elitist and folk-pleasing, or epic and mythopoeic - in hindsight clearly didn’t spring from any desire to uncritically depict reality, let alone endorse it—but was feverishly non-realist, fantastical, phantasmagorical.

Rebecca West flying to Nuremberg for the trials saw the architecture below - German Romantic, Nazi neoclassical - as yet more evidence of how the country’s imagination had malingered at infant-stage, at fairytales with all their monsters and consolations. In his classic of post-war children’s literature The Neverending Story, Michael Ende allegorised fascism as the result of his country’s stifling then glut of the fantastical. For Dr. Bronowski fascism wasn’t the ironically dark triumph of a too-cold rationality but of make-believe “with no test in reality.”

Impressionism and expressionism, as derided by our philistine Professor Wendland, didn’t scorn reality any more than did modernism or even post-modernism. Paintings that created the illusion of recording raw sense impressions, conceptual art that put urinals on a pedestal, novels that took us into a Dublin shit-house, short stories that incorporated cartoons and ads can all be understood as realisms of a richer reality. (Or as Ursula Le Guin put it in her short story ‘The Diary of the Rose’, “What we call psychosis is sometimes simply realism.”) By contrast, Edwardian novels with their mannered euphemisms, 50s American fiction that suppressed references to pop culture in a phony grab at universality were the unrealistic ones. As Jon Baskin wrote in an essay for The Point Magazine:

What is the most real thing? This is the question that artists like [David Foster] Wallace want to use their fiction to investigate, and which the realist so often behaves as if he has already answered.8

Pushing artistic form so it probes further into ‘the real thing’ beyond consensus reality: this synthesises the presumed aim of realist art to capture reality accurately and comprehensively with the aims of experimental art (breaking with convention, subverting the status-quo). Such a synthesis would especially ring true for Professor Wendland and his fellow Nazis. Because what was one of their contemptuous terms for modern art movements like impressionism and expressionism? “New Realism.”

But even this synthesis - experimental art as realism by other means - isn’t really what realism is. In the next part I’ll be defining it first by jettisoning all it’s not. For one reason why audiences, critics - and experimental poets - get so confusedly angry or complacently ignorant about realism is that few talk about it accurately. Which considering its ‘realism’ under question is, you know, ironic.

It was fun watching the panel, who, like most, were nice about other authors at the festival and critical only of absent, consensus-bad ones, try give this bananas take some ‘refuse to condemn’-style lip service, even though the poet wasn’t there and being quoted second-hand: you know the kinda stuff, ‘I so get why they’d say that, and while I wouldn’t necessarily put it that way myself…’

Quotes taken from The arts of the Third Reich by Peter Adam, as useful a primer on the historically cyclic, art-hating moralisation of art as anything on Comrade Marshal Zhdanov.

See Sontag’s essay ‘Fascinating Fascism’—among other things a takedown of Leni Riefenstahl, from a time when takedowns deserved the word.

Just take Erich Auerbach: founder of our modern conception of artistic realism, chased out of Germany by the Nazis.

Althusser in ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses’: “all ideology represents in its necessarily imaginary distortion not the existing relations of production (and the other relations that derive from them), but above all the (imaginary) relationship of individuals to the relations of production and the relations that derive from them. What is represented in ideology is therefore not the system of the real relations which govern the existence of individuals, but the imaginary relation of those individuals to the real relations in which they live.”

Regarding that presumption, here’s Peter Adam again: “On a political level the controversy between realism and abstraction lasted well into the postwar years. However, the idea that abstract art stood for progress and representational art for conservatism is as misleading as the idea that the artist’s preference for one or the other implied an act of political allegiance. The polarization of these two categories of artistic debate is too simplistic and cannot be used to explain Fascist art.”

Making a strong case for this otherwise wrongheaded valorisation of abstract art is Guardian commenter Forthestate: “[It] was, in many ways, a reaction to two world wars, and the build up to them, and a holocaust; many artists simply refused to speak to people in the common language of society, turning away from values that disgusted them to a private language that demanded a dialogue on the artist’s terms. It is unsurprising that totalitarian, authoritarian regimes have always decried such art as the height of decadence. Adopting private symbols that reject those of the state, or indeed society in general, it speaks a language that they cannot control, and therefore fear, and its demand that adherence to the official, permitted language is suspended on behalf of the individual’s private vision, in order to enter into it and understand it, is anathema to the controlling instincts of those that would appropriate the whole of that language to their control. It is unsurprising that a century as violent and apocalyptic as the 20th produced it, and it is almost always reactionaries who reject modernism in favour of fossilising art in the principles of some mythical period of past perfection, usually a crudely understood ‘realism’.”