Knock knock

Who’s there?

Knock knock

Who’s there?

Knock knock

Who’s there?

Knock knock

Who’s there?

Knock knock

Who’s there?

Knock knock

Who’s there?

Knock knock

Who’s there?

Philip Glass

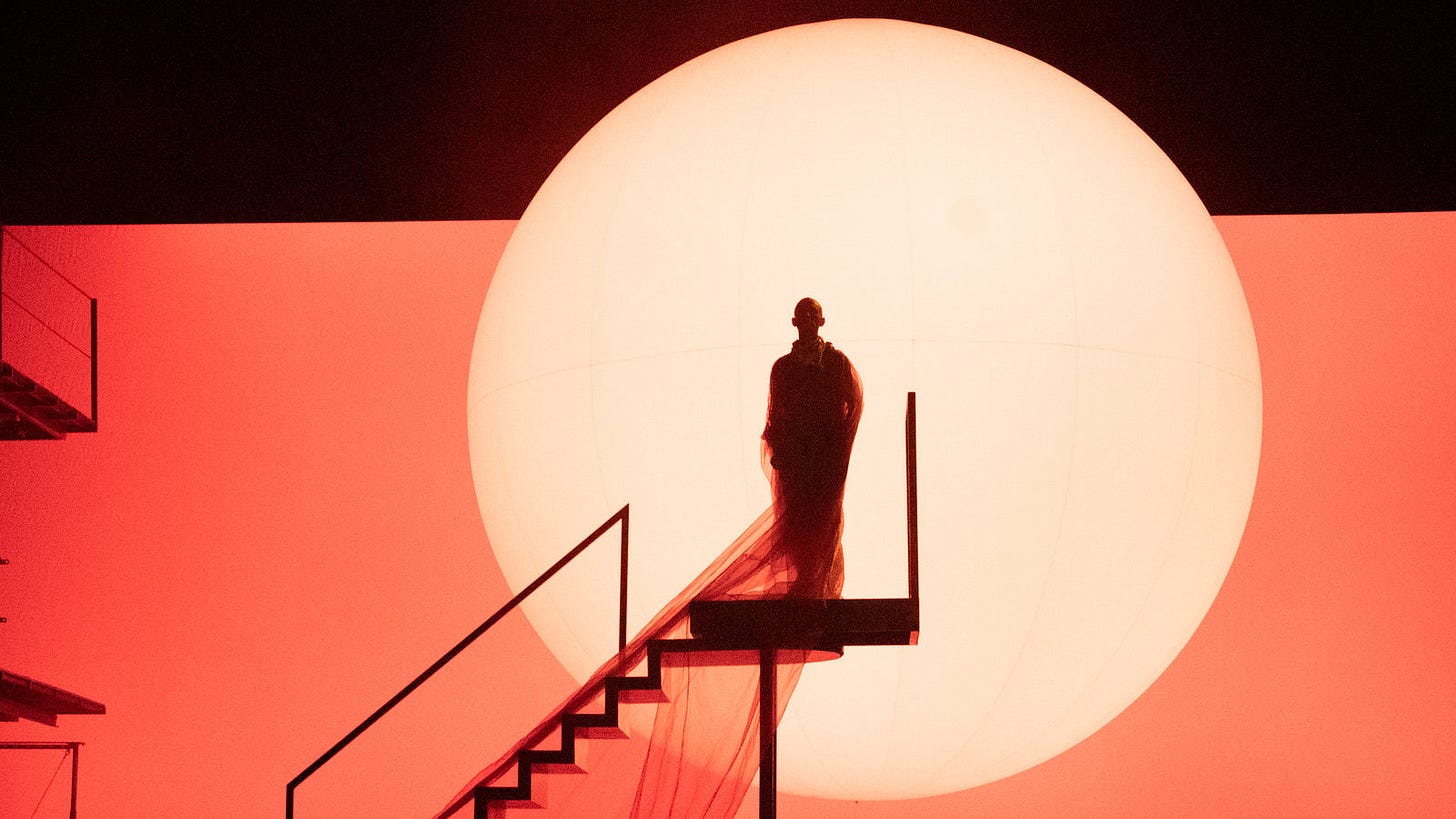

Last month I watched Philip Glass’s opera Akhnaten, in which the performers take even their steps tai chi-slow and make Kabuki grimaces for minutes on end. At some point (how refreshed those words) in one prolonged scene - as I recall, a trio of gods(?) were glaciering downstage while jugglers in jumpsuits bounced big eggs à la Sleeper or the Oompa Loompas during Mike Teevee’s demise - I got to thinking about the value of elongation, repetition, and excess.

Those Glassy arpeggios and ostinatos are often described as hypnotic or entrancing.1 But as Glass himself warned John O’Mahony for The Guardian:

The trance aspect of the music is a misnomer... It’s music that requires alertness all the time—if you space out, without any doubt you’ll get lost. The audience might have that privilege, but we don’t.

Making an allowance for the audience is also a mistake. His music requires alertness from us too—but to what? Nothing, according to opera critic Donal Henahan; reviewing the premiere of Akhnaten for the New York Times, he wrote that it was “one more example of going-nowhere music” that offers only “backgrounds of continually repeated, barely varied sound patterns. They stand to music as the sentence ‘See Spot run’ stands to literature.”2

Judging how Glass’s music stands to film might be more helpful. In their textbook Film Art David Bordwell, Kristin Thompson and Jeff Smith explain the critical role of Philip Glass in scoring eco-art-movie Koyaanisqatsi: “Throughout, [his] rhythmic and repetitive score provides a firm base for the imagery, with changes in instrumentation often signalling a shift within a section.”

‘Signalling’ here is key. Glass’s rhythm and repetition have to my mind at least two functions. One is suspense - how long will this pattern go on for? - and, related, the other is to make the “barely varied patterns”, when they do vary, unmissable. They’ve been signalled. (See the entry of the percussion in Akhnaten; or the sped-up strings then blatting horn section at the peak of Pruit Igoe.)

Working together, these two functions help the structure of Glass’s music avoid, contrary to popular and critical belief, getting lost in the sound and instead clarify it; they delineate the transitions, of all kinds—tone, tempo. His is an art of thick lines. The structure of his music doesn’t, as with program music, sink to subliminal notice like bones but stands out for appreciation. So it’s never been unthinkingly or meaninglessly repetitious. He knows what he’s doing. What he’s doing he knows.

In my newsletter on the necessity of re-listening/-reading/-watching, I wrote that repeating your experience of an artwork makes whatever pattern it might have (i.e. what makes it art) easier to discern. Not least because all your first listens, reads, watches have to initially defog your ignorance of the work, and only once you’ve taken it in as a whole can you legitimately assess the point of its parts.

Repetition within an artwork itself seems to have the same role: to insist on the work’s form. (Note that I’m not really talking about repetition over long sections; the nine parts of The Satanic Verses have a rondeau structure, but it’s not something you’re gonna notice at the page-by-page level. I more mean the obviously repetitious.) As I repeated for emphasis throughout my abyss dive into Borges, “repetition is emphasis.”

Look at Tolstoy. In a note on their translation of Anna Karenina Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky wrote that his repeated use of the Russian word for home, dom, in the opening chapter shouldn’t be queasily avoided but replicated in English. There’s the way its repetition declares from the outset like a town crier one of the novel’s main themes; there’s the avoidance of subbing in false synonyms - ‘house’, ‘household’, ‘homestead’ - which with their subtly different meanings would dilute Tolstoy’s purpose with dom; and in its tolling repetition there is a not irrelevant church-bell sound.

This usefulness of repetition ought to be most apparent in films, which can repeat dialogue, sound effects, musical motifs, actorly gestures, visual imagery. Pauline Kael was nonetheless sceptical, writing in her essay ‘Fantasies of the art-house audience’:

I have never understood why writers assumed that repetition creates a lyric mood or underlines meaning with profundity. My reaction is simply, “OK, I got it the first time, let’s get on with it.”

But audiences, art-house or otherwise, are rarely as conscientious as her. Sourcing Alex Garland’s literary inspirations to account for his horror film Men, I pointed out his repeated references to The Green Man, novel and folklore both, as well as to flowers, fruit and seeds. “There are dots here for you to connect, they say, so it’ll pay to pay attention: see the pattern, work out the overall design,” as I wrote elsewhere. And yet Men’s still largely derided as a throw-signs-at-the-wall-see-what-sticks mess of a film. I guess sometimes even artworks repeat themselves till they’re green in the face.

One element that repetition can emphasise is itself; repetition can be about repetition. This can have a positive value; composer John Cage in his notes to a show by Andy Warhol wrote that:

Andy has fought by repetition to show us that there is no repetition really, that everything we look at is worthy of our attention

‘Einmal ist keinmal’ goes a German proverb: once is never. According to Cage, though, always is only. John Updike, meanwhile, saw a negative value in the same show, writing in his book More Matter that:

The repetition that was one of Warhol’s key devices - two Liza Minnellis, ten Elizabeth Taylors, thirty-six Elvises, one hundred two Troy Donahues - has a mocking effect.

And of Cage’s profound soundings, he went on to write:

To me the message seems the exact opposite… that everything is emptied and rendered meaningless by repetition. Warhol himself stated: “When you see a gruesome picture over and over again, it doesn’t really have any effect.”

Repetition as mockery—consider the (hopefully) schoolyard gag of “Stop repeating what I’m saying!” / “Stop repeating what I’m saying.” And repetition as the enactment of vacuousness—consider the stupid giddy thrill of this scene from A Clockwork Orange:

Talk about ‘the road of excess’. (It’s like that bit in Robert Musil’s A Man Without Qualities: “A motorcyclist drove down the empty street, arms and legs rounded in an O, and came back up with the sound of thunder; his face displayed the seriousness of a child who attributes the utmost importance to his howls.” A line to salve yourself with the next time you get interrupted by the violent fart-past of some kid on his unmuffled moped.)

Like Kubrick, others have used the inanity of repetition for comic effect, sometimes for its own sake:

And sometimes to make a point, as with this Brass Eye ident that satirises the overblown graphics of current affairs TV (note that in the actual episode of Brass Eye the ident goes on for about 30 seconds):

In both cases the point of, the pleasure in, the comedy is ‘How long can they keep it up?’ We’ve returned to the idea of repetition as a type of suspense. Dance music, for instance, works through repetition and elongation, holding off when the variation will come in order to make it land all the better when it does. Comedy band The Lonely Island singled out and drew out this very feature with their song ‘When will the bass drop?’, in which repetition and withholding variation becomes a sort of hellish madness.

The late Milan Kundera, commemorated here, told a story in his book Testaments Betrayed of when he was a child banging away the same few notes on the piano - a Philip Glass arpeggio before its time - till his dad, a music theorist, came in and yanked him off the stool and put him in the corner. Maybe it’s this vacuousness in repetition his dad was thinking of when, as Kundera relates elsewhere in the book, he was recovering from a stroke and heard a snatch of a record then strained to say to his son, “The idiocy of music.”

But according to comedian Dylan Moran:

Some people can’t get past the stupidity of repetition, they probably would squirm under mantra mediation—but why isn’t it letting me be clever by understanding it?

Maybe the way to reconcile Kundera, père et fils, with Dylan Moran is through understanding what purposiveness, if any, there is behind the repetition in a given artwork; actual excessiveness versus its appearance; the opposite, then, of a mindless trance. “A working definition of art: the appearance of excess that is in fact a total control. In the film The Red Shoes the ballet fantasia sequence keeps going longer than what is functional, than what you’d ‘reasonably’ expect… The appearance of excess then is simply when you go beyond the received wisdom of how something is meant to be, its formula or form.”

As William Blake wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom”; and further, “You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.” Granted there’s something of the Hellraiser Cenobite in these words, but they hold a great truth. Art is controlled excess, necessarily too much; keeping with these Taoist dialectics3, we might add that the point of repetition is variation.

Without the interrelated device of repetition/variation, there can be no pattern. And whether it’s Philip Glass’s music and its stark formalism or seemingly formless works like Jackson Pollock’s where the fluid mechanics behind his so-called drip-painting needed precise repeated technique, without pattern there can be no art.

If not samey. Glass told The Guardian about the first time he played his breakout piece Music in 12 Parts to a friend, “and when it was through she said, ‘That’s very beautiful; what are the other 11 parts going to be like?’”

Another not to take Philip Glass’s music seriously was British satirist Chris Morris (whose other musical parodies I covered here): make sure to listen to the end of this glorious nonsense.

I wonder what others there might be. ‘The point of a novel’s scenes and summaries is to justify each other.’ ‘A shot without a cut is like a cut without a shot.’