It’s not only because the most annoying people in the world have had their fun with Die Hard that Eyes Wide Shut is next to get touted as a Christmas movie. Neither has the film finagled its way into that category by just happening to be set at Christmas, set-decorated with tinsel. Eyes Wide Shut is a Christmas ghost story by way of the spirits of the unconscious. And like Charles Dickens’s most famous one it has an old-fashioned warning to make.

Ever since Eyes Wide Shut came out in September 1999 its reception has been, for better or worse, coloured by Stanley Kubrick’s death six months earlier. To its admirers the film is a fitting swansong; to those not impressed the question remains open whether perfectionist Kubrick could’ve pulled off the film better had he lived long enough to give it his finishing touch. Not least by making the film less uneven and episodic, a common criticism back then and now.

It’s always been wrong. Throughout his career Kubrick fitted together the parts of his films via pairings: parallels, contrasts, inversions. The reason Full Metal Jacket comes in distinct halves isn’t so we all prefer the first to the second but so they can jar and harmonise with each other (I think it was trying to suggest something about the duality of man, sir—the Jungian thing); meanwhile the whole of 2001: A Space Odyssey is a mirror that folds on the hinge of that famous match cut from bone-club to space nuke.

As for Eyes Wide Shut, it’s not, or not only, episodic. Kubrick paired each episode with another - locations visited twice, characters met twice or doubling for each other - and so established a pattern of point and counterpoint: horny expectation then sordid reality, the inflamed night before then the cold light of day, dreams then waking—apt for a film based on Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle or ‘Dream Story’. This pattern binds and defines the film. It’s what Kubrick needed to best dramatise his story: the quest of Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) to avenge the fantasy infidelity of his wife Alice (Nicole Kidman) with some of the real kind, and what that quest might cost…

1. On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me, flirtation at Ziegler’s party

The first pairing comes when Bill and Alice attend a glitzy Christmas party hosted by Ilona and Victor Ziegler (Sydney Pollack). While Bill catches up with a friend from med school who’s playing piano for the party, Alice is chatted up by a handsome fiftyish man called Sandor.1 With his tux, Old World accent and Sam Eagle eyebrows Sandor seems to have wandered into the film from a Ferrero Rocher ad, yet Alice is not un-intrigued. She dances with him but then spots her husband across the ballroom with a beautiful young woman on each arm.

Called Nuala Windsor and Gayle, they’re fashion models, the latter of whom Bill had once been a Good Samaritan towards, albeit intimately: removing grit from her eye (a romantic device that traces its lineage back through Brief Encounter to Anna Karenina, both stories about infidelity). The models flirt hard - by the end they’re practically frottaging Bill - and he does flirt back, though in a grin-faced way, as if he’s half his age. At the same time Alice’s tipsy flirt with Sandor has the cloying girlishness of Eartha Kitt singing ‘Santa Baby’. Our married couple are babes in the woods here.

Covetous Sandor encourages Alice’s jealousy: “Don’t you think one of the charms of marriage is that it makes deception a necessity for both parties?” Since she’d told him she managed an art gallery, he propositions her by inviting her upstairs to see the Zieglers’ sculptures.

She turns him down, at first with a hedging “Not just now” then with a firmer “It’s impossible”—this explained by pointing out her wedding ring. As for Bill, his squiring of the fashion models becomes them escorting him: he asks where to, and Nuala replies, “To where the rainbow ends.” Before we find any pot of gold, and before we’re sure Bill firmly declined a proposition like his wife, a hench security guard intervenes and escorts Bill away to see their host.

2. Two deceptions and confessions

Ziegler, semi-nude - black braces over grey chest-hair - sneaks Dr. Harford into a bathroom to aid another beautiful young woman, sprawled nude and O.D.’d. After Bill’s confirmed the woman, Mandy, is not in mortal danger, Ziegler asks him to keep the close call a secret. Bill does so, even from his wife (for now). The next night Alice squeezes her face in a vanity mirror, sighing, then takes out from behind her reflection a drug stash;2 she then proceeds to roll the most weed-heavy joint this side of the Camberwell Carrot. With her and Bill suitably stoned she quizzes him about his absence at the Zieglers’, wondering whether he wasn’t fucking the fashion models.

Bill denies this and claims he was helping Ziegler who “wasn’t feeling too well.” Seeing as Ziegler could’ve been caught in flagrante with “an overdosed hooker” by his wife or other guests, chances are he was a little out of sorts, so Bill has told Alice a half-truth. But what’s the other half? Moments later he says, “I would never lie to you.” He’s deceived her nonetheless. The film’s first deception, narratively speaking, is Bill’s of Alice.

He deflects from it by asking about the man she’d danced with. She admits Sandor propositioned her, yet her own husband brushes off this encroachment as understandable, considering how beautiful she is. At this ‘compliment’ Alice smarts. Debating whether one-track-minds occur in both men and women, she asserts his female patients fantasise about him. He denies this on the basis that women, to oversimplify it, haven’t evolved as horny as men. This spurs Alice to tell him something she’s kept to herself until now.

What other scene in cinema goes from 0-80 as sharply as this? For its first half Nicole Kidman’s performance is like an improv class had gotten the prompt ‘Play a drunk in a panto’, while Tom Cruise acting stoned looks as though a fly keeps getting in his face. But on the hinge of Alice saying “titties!” in a helium-high-voice then having a laughing fit, we pass from cringe to can’t-tear-your-eyes-away.

With a glower and the words, “If you men only knew” Alice begins her confession. Once on holiday in Cape Cod she crushed on a naval officer so hard she was prepared to lose her husband and daughter for a chance to have sex with him.3 She couldn’t sleep at the prospect of seeing him in the hotel dining room the next day. The suspense of her monologue hangs on how she’ll describe her reaction to finding him in fact not there: “I was… relieved.” Temptation felt sincerely, passionately, but it passed. It stayed a fantasy—the first dream of our ‘Dream Story’.

Though Alice’s cucking of Bill was counterfactual - infidelity in the subjunctive mood - it’s enough to make something in him snap. He might’ve bought Gayle’s compliment that doctors are “so knowledgeable” but that’s part of his delusion: he doesn’t even know what he doesn’t know. The film started with him assuring Alice she looks perfect without looking at her and instead at his own reflection; he misplaces his wallet, forgets their babysitter’s name moments after Alice told him it; and his first interaction with Mandy the OD’d model is to tell her so often to “open your eyes” that the words become pointed.

What were Bill’s eyes shut to? That men find his wife desirable? He’d acknowledged as much on the brink of their row (of course his wife would be desired by other men). Then is it that she desired other men? He’s a worldly grown-up, this ought not be a surprise (she desired him after all). Rather, the stunning blow is Alice reasserting, within the bounds and binds of their marriage, her separate inner life, her fantasies, which not only exclude him but are predicated on leaving him and their child. She uses her confession as a blow, to beat him in their domestic row or at least force a stalemate, all via the typical trump card (it’s Christmas, let me mix metaphors and drinks) of an adolescent: ‘You don’t know me!’4

Alice’s ‘deception’, then, while coming narratively after Bill’s, chronologically came before. As far as he’s concerned she shot first. During her harangue moments earlier she’d asked, “What makes you an exception?” In (re)discovering that his wife has sexual secrets independent of, even in opposition to him, something to which he’d been blinded by his hoary take on gender roles, Bill has discovered he’s not an exception, i.e. suffered a narcissistic injury. And injury seeks revenge.

Before his glare at her seethes into anything worse the phone rings and he’s spirited away on a house call. And so we’re off on what’ll turn out to be a sex odyssey to pay back his wife; she’s called Alice but it’s sensible Bill about to fall into wonderland. When at last he crawls out of his hole he pays back his wife another way: by confessing to her in turn.

The film elides that confession, cutting to the morning-aftermath. We already know what it was about; he’d sobbed to her the night before, “I’ll tell you everything”—i.e. his attempts at infidelity, which in the end stayed fantasy, like hers. But unlike hers, his had risked so much, for himself and others. Tear-stained Alice just found this out; he, though, was reminded of it continually if not systematically. That system forms the structure and moral universe of Eyes Wide Shut. So what is it?

3. 🎶 Night and day, you are the one 🎶

In the first half hour of the film, its pairings come in the form of sequences intercut with each other, like Bill and Alice’s Christmas party flirtations, and the montages of them going about their separate lives the day after the party. Following her confession that night, the paired episodes come a day or two apart in story-time, and from half-an-hour to an hour apart in screen-time. Below I’ve arranged the episodes in two columns: point and counterpoint, illicit set-up followed by sobering pay-off, both listed chronologically. I’ve then colour-coded each episode to pair it with its partner:

Most of the first column covers the night before, most of the second the day after, though not all in the daytime—enough, though, to define the pattern as a night-and-day one. In the ‘night’ column Bill is almost always passive, moved either by (in)convenient circumstance or the will of others, like in a dream: security guards, phone calls, door-bell rings, people who are concealed or who catch him concealing himself. In the ‘day’ or ‘waking’ column Bill becomes more active, gumshoeing his way from this informant to that, till the point he turns informant: confessing all to Alice.

The third part of Kubrick’s pattern which resolves night and day is that confession, is Bill’s take-home from his various misadventures. Let’s start with the first one.

4. Maiden Marion

When Sandor the Hungarian was chatting up Alice at the Zieglers’ Christmas party, he told her marriage used to be how women “could lose their virginity and be free to do what they wanted with other men... the ones they really wanted.” (“How interesting,” Alice replies to the mini-lecture.) This theory gets inverted by Marion Nathanson, daughter of the patient whose death was announced in a phone call to Bill, right at the birth of his newfound jealous rage towards Alice.

At the Nathansons’ apartment Bill offers Marion trite condolences, her dad lying on his deathbed in the background. Their talk then moves towards the light of her coming marriage, to a man called Carl. Contrary to Sandor, Marion doesn’t view the prospect of marriage as freeing but restricting. For she’s in love with Bill, so she declares, having smothered him with kisses like the Scandi stereotype in a 70s sex comedy. Even more stereotypically, they’re saved by the doorbell, announcing her fiancé. (A neat bit of acting from Tom Cruise when he subtly wipes Marion’s lipstick off his mouth after greeting Carl.)

If Marion’s nuptials are no bar on her unfaithful passion for another man, why would they’ve been for Alice? The next day, Bill works himself up again by imagining his wife fucking the naval officer5 (or rather he concocts or co-opts her own fantasy of it). Needing to discharge, he phones Marion’s apartment. But it’s Carl, the potential cuckold who answers, as if psychically sensing his rival. Bill hangs up, foiled or saved again. From what?

Notice how Alice and Marion, and Bill and Carl, have a dreamily askew resemblance to one another, right down to the women’s matching fringes: a duo of doubles. If Marion and Carl’s nascent married home is meant to parallel Alice and Bill’s established one, who or what might Marion’s father - in the background of multiple shots - stand for?

Marion has just lost her father like Bill’s young daughter Helena will one day, definitely through death—but potentially as well through a home broken by adultery. Bill’s phone call to Marion that might’ve hatched their adultery is intercepted by Carl, his double. It’s as though he were heading himself off.

This sets the pattern. Every time Bill chases a missed opportunity from the night before he encounters a block, which can be read as a warning. Warnings of dissolution, corruption, violence—or, as most starkly symbolised by Marion’s father, death.6 For his body is only the first of a pair we’ll see lying dead by the end of the film…

5. From cockblocked to cocksucker

Having left Marion with their honours intact, Bill walks the streets, where a gang of frat boys appears. They’re rampantly heterosexual, one boasting about aggressive sex he had with a woman: “I’ve got scars on the back of my neck!” They turn this aggression on Bill, verbally and physically, asking what team he plays for then shoving him into a car. They explicitly make him feel small, one yelling, “I’ve got dumps that are bigger than you.” On the heels of his curtailed embrace with Marion comes his emasculation.

This pseudo-gay-bashing scene gets paired with a scene the next day when Bill goes to a hotel to try to find his pianist friend Nick (Todd Field), who’s in trouble for sneaking him into a masked ball the night before. Bill quizzes the hotel receptionist—played by Alan Cumming with campness set to Kenneth Williams. The receptionist tells Bill a roughed-up Nick was escorted in and out of the hotel by “big guys” (in contrast to smaller-than-a-dump Bill), hands spread on the word ‘big’. Salaciously he tells the story of Nick’s manhandling, eyeing up and preening at his listener all the while.

These scenes are Kubrick’s invention, developed from an Austrian TV-movie adaptation of Traumnovelle in 1969, which itself developed a scene from the source novel. In the novel, an insolent student barges into Bill’s counterpart Fridolin; in the TV-movie the student then gives Fridolin a come-hither look. By the time of Eyes Wide Shut this glancing incident has grown and split into a pair of scenes to cover the physical and carnal threats to Bill of homosexuality.

The physical: the gang of (we can presume) straight men who assaulted Bill in the night-time at the trumped-up charge he was gay. The carnal: the gay man the day after who reads Bill as gay, or at least hopes he is, while titillating him about another man’s assault. Male homosexuality as a reverse sublimation of man-on-man violence: physical tension diffused into sexual tension. Such are the perils of a man leaving the shores of the family hearth and going a-sailing for sex: men will fuck you or fuck you up.

6. Unsafe sex

Following his assault by the frat boys Bill has a chance to, in his eyes, remasculate himself. He’s picked up by a beautiful young woman, who asks whether he’ll “come inside with me,” hohoho. But she picked him for his money, not manliness. In her building lobby hangs an ad for ‘body-oriented psychotherapy’, a good euphemism for the services she offers (and a good subtitle for Eyes Wide Shut).

Her name is ‘Domino’: both a game of chance - like the chance that Bill’s taking by hiring her - and a cloak you wear at a masked ball, the sort he’ll hire in a couple of scenes’ time. He and Domino agree a price then kiss, but before they get further he’s interrupted by a ring-ring, pun intended. This time it’s not somebody else’s fiancé like Carl but his own wife, Alice: phoning to check when he’s back.

Wilted Bill leaves, though insisting on paying for sex he didn’t have (what a guy). In the hope he’ll have it yet he returns the next day to Domino’s, not the pizza place and bearing cake. She’s out, as he hears from her room-mate Sally, who, having heard of his sweetness, lets him in anyway. Like the fashion models before her, Sally flirts hard with Bill, brushing against him in the poky apartment, as the lights on the Christmas tree in the back turn red. She then winds him down and explains Domino’s absence: she’d had a test result saying she’s HIV+. The lights on the Christmas tree turn blue. (Note too Sally’s wavy locks, the same as Marion’s and Alice’s.) After this cold shower reveal, what Sally offers Bill next is no longer sex but coffee—the cliché euphemism put in reverse.

Sex offered at night but foiled before it occurs; then the day after a hazard sign associated with disease or death… In Domino’s case the foiling is a ‘there but for the grace of God’ close call.

This pattern of close calls we ought now infer actually began with the security guard at the Zieglers’ Christmas party, who stole Bill away from the fashion models. After the men left the frame the two women exchanged looks, like Roy Batty and Pris in Blade Runner do after J.F. Sebastian leaves them—as though a sinister plan has failed or is afoot…

Just before the security guard came and did what his job-title says, Gayle told Bill she and Nuala would take him to “where the rainbow ends.” Before he can get there he has to hire something else, at a shop called Rainbow Fashions.

7. Up the aisle

The proprietor of Rainbow Fashions, a Russian called Milich, is another man anxious about virility, asking Dr. Bill to examine his hair-loss. After cursory advice, Bill has to stop him there: he needs a cloak and mask fast to get to the ball on time.

Milich moodily proceeds with the transaction then halts at a noise from a backroom. There he discovers two Japanese men with clothes off who’ve been consorting with his doll-like, adolescent daughter. Milich locks the men up, warning them he’s calling the police, then tries to beat his daughter. She scurries behind Bill and whispers what looks like a proposition to him.7

The day after, when Bill comes back to Rainbow Fashions to return the domino cloak, sans mask, the atmosphere has changed: from outraged morals to compromised ones. Seemingly finished with the doctor’s transaction, Milich turns to say a businesslike farewell to the Japanese men from the night before, one of whom even blows a kiss at his daughter. The same daughter whom Milich now insinuates Bill could have under arrangement—father turned pimp.

Barring Bill’s goodbye to his babysat daughter at the start of the film, there’s another ‘father-daughter’ scene that precedes this one with Milich: when Alice danced with Sandor. Grey-haired, worldly wise, Sandor is a “You’re old enough to be my dad!” jibe made real, while in her flirting with him Alice pouts and simpers like a little girl.8 And it’s this father-figure who’s the one to give her a talk on the true purpose of marriage.

The Soviet Russians during their crash-course modernisation of Central Asia tried eradicating, among other backwards customs, the one of bride-price. But on closer examination this custom was not, or not only, a buying-and-selling of women, so argues anthropologist Adrienne Edgar. It was also a rational demand for compensation to a tribe that, in losing a daughter to another tribe, lost their productive edge twice-over: a power to work and a power to make more workers. Such a loss wasn’t symbolic but eminently material in a desert environment where survival margins were so slim.

While a modern man like Bill can hire a sex worker for the night, in order to obtain the lifetime rights to a woman’s productive and reproductive power he once would’ve had to have paid the bride-price. Which is why whenever we speak in modern usage of a father ‘giving away’ his daughter in marriage the redacted second half of that phrase is ‘for free’. Milich pimping out his daughter isn’t a perversion so much as reversion of the marital relationship that Bill benefits from with Alice.

Or, more darkly, that Bill benefits from with his daughter. For he isn’t only a married but a family man; one day he too might give away his daughter.9 But in straying from his own marriage, if only for 24 hours, he’s gotten a franker look than he might’ve liked at marriage’s original, transactional underside. The Soviet Russians couldn’t iron it out of Central Asia; and it still lurks under the costume of civilisation in the hire-shops and family homes of the US.

8. The Blue Ball

Marriage lurks even at an orgy—the masked ball that Bill trespasses on for the film’s centrepiece. He does so using the password, ‘Fidelio’, which according to a facetious Nick is merely the name of a Beethoven opera.10 Of course it also means ‘faithful’ and is twinned with infidelity.

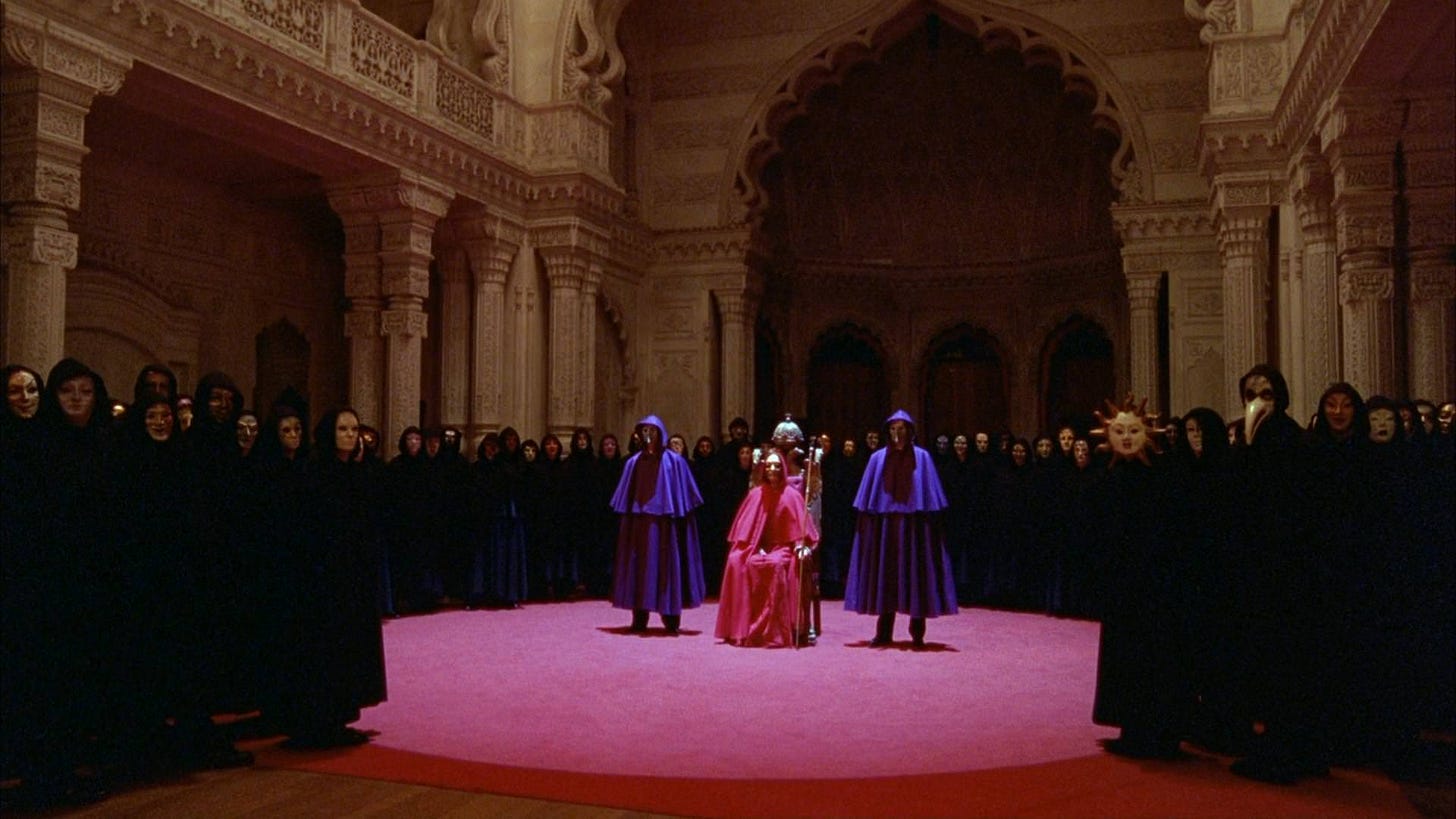

Drawn by Nick’s night-song of backwards Sanskrit music, Bill enters a room with the tracery of an orientalist harem but the apse-like space of a church. There a man in priestly garb officiates a ceremony11: he swirls a smoky censer around a circle of knelt nude women in masks; then, at the thump of his staff, they pair off with a lucky guest each—from ‘I do’ to ‘I do you.’

Here, at the lowest circle of sex, people have become abstract. When the knelt women passed a kiss around their circle, they did so not from face-to-face and neither from mask-to-mask but with a theatrical gap left in between. As the orgy heats up, a man and woman top-and-tail each other but with masks on, less sixty-nine than sixty-mime (or a charade in Ziegler’s later words). There is un-mimed fucking at the ball, but always masked, without faces, without identity: only bodies, for only the body.12

Since the ball is the hinge-point of the film, it merges, in fact doubles, our previous pattern of excitement and comedown. After the staff-thump ceremony a masked nude woman escorts Bill away, not for sex but to warn him of danger.13 This time, though, it’s the comedown that’s interrupted: the woman gets escorted away from Bill by a masked manservant. A little later, a second masked nude woman (at the nod of another man) engages Bill, seemingly for sex. But now they’re interrupted by the first woman (as the lights in the background turn blue: always this alternation between the red of romance and passion, the blue of cold showers and balls). She takes Bill aside to warn him away again, only for them to be interrupted in turn. (It’s as though this pillar-to-post motion is meant to stand for his excitement and anxiety winding each other up to manic proportions). This time it’s Bill who’s escorted away, as he was at the Zieglers’ party, by a manservant—but on false pretences.

He’s taken back to the apse-like room, where the red-robed sex pope awaits in a ring of the masked crowd. Asked again for the password, Bill repeats ‘fidelio’. The sex pope says that was the password for admittance: what’s the password for the house? Bill doesn’t know—he’s been rumbled. The sex pope orders him to take off his mask, exposing his identity. It’s a variation on the dream where you’re naked while everyone else is clothed; in fact Bill’s then ordered to take off all his clothes, which, considering the tenor of the ball, hints at some further, fucked up sexual humiliation, or worse.

Bill is saved from any such at the last moment by the masked woman who’d tried warning him away: it’s Mandy, as Bill and we might now infer, the “overdosed hooker” whose safety he attended to at the Zieglers’ party. She trades places with Bill, who’s sworn to secrecy on pain of “dire consequences” for him and his family.

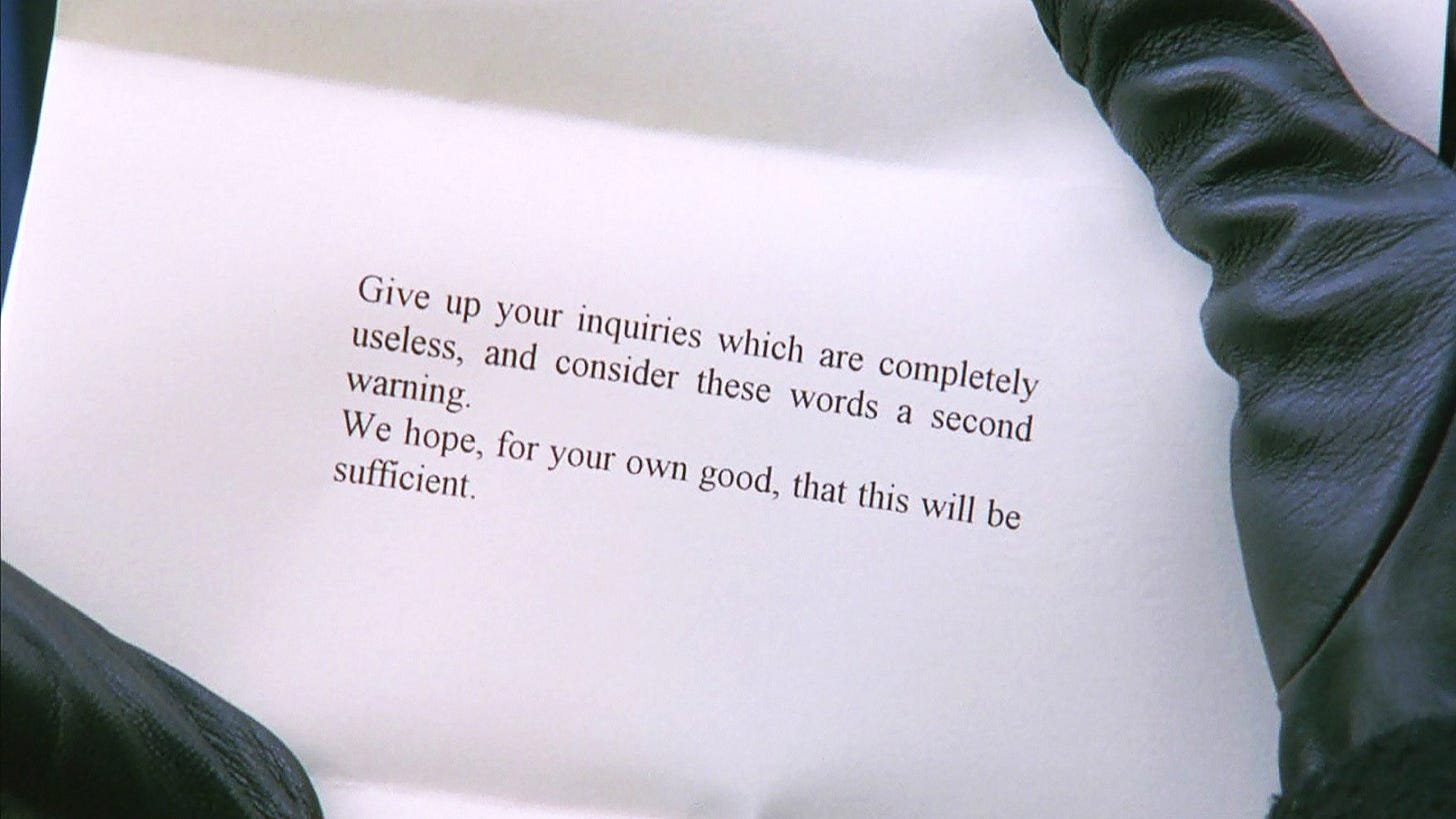

Following this dark night of the libido, Bill returns to the site of the masked ball in the cold light of day, but the gates are sealed. A security camera turns on him at the same transfixing pace as two masked figures on a balcony did the night before. Moments later a cadaverous servant drives up and hands Bill a note.

It won’t be sufficient, not after he reads in the paper of Mandy’s supposed death-by-overdose. He tricks his way into a morgue to inquire after her body.

In the never-had, now-dead Mandy, has he gotten himself a like lost-opportunity fantasy figure to pine over as he thinks Alice does with her naval officer? Was that all the balance needing redressing? Read figuratively, then, his attempts at infidelity would be just another charade; what he really wanted was a guilty sexual fantasy to confess to Alice in turn. If so, the film would’ve ended there, or even at the morgue. But Bill also needs to know: what did it all mean?

When it comes to this film, though, that question doesn’t have any bottom, in the same way it doesn’t when it comes to what you ‘see’ during sleep with your eyes wide shut. That’s why we have to go next to the land of dreams…

9. He’s dreamy

The film’s episodes in their night-day pattern of arousal and petite-mort are not the whole story of Eyes Wide Shut. Neither is the fact that the episodes in the first half of the film all get curtailed. Had that been the story, the film would’ve been more like a sex comedy, in which a hapless horny man is forever cockblocked by the universe.14

Instead the film’s presiding spirit reveals itself when Bill gets back home from his misadventures to find Alice laughing in her sleep over a dream, which on waking she tells him in tears.

Over the film’s opening titles and montage we heard a waltz till it was silenced by Bill turning off his stereo: as well as on the motion-picture score it’d been playing in his apartment, i.e. it was ‘diegetic sound’. So too Alice’s dream happens in the world of the story, but its central, anguished place in the film sends out ripples that the film is itself all a dream. Not in the cheesy sense that the events in it didn’t happen. Rather that dreams for the film are also non-diegetic: as with a score or soundtrack, they’re part of the artistic form of Eyes Wide Shut.

Take how critics have always derided its stagey performances and sound-stagey locations. There’s mad Marion, flaming Alan Cumming, Milich with his Russki the Grouch act. Then there’s the cityscape of New York as recreated in Pinewood Studios: for all the painstaking production design it looks uncanny, in no small part because of the lack of pigeons, as well as the way it’s lit whether at night or day (we never see any sky—Eyes Wide Shut is another film that could’ve been called Dark City). Outside of studio footage, Kubrick used stock or second-unit footage of New York for establishing shots; back-projection for the view from the rear window of Bill’s taxi; while in one shot he dollied the camera backwards as Tom Cruise walked towards it while the street around was digitally painted in.15

If Kubrick had meant to tell his film in a dream-mode then all of the above isn’t evidence he failed to pull off a convincing replica of New York City and its people. The ersatz setting, the broad performances reinforce the off-kilter, cobbled-together quality of a dream. Or in the words of Ziegler explaining away the masked ball (and the film for that matter): it’s all staged, fake.

The dream-mode extends to Eyes Wide Shut’s narrative drive, such as it is. On first watch it might seem less a gripping story than a “barren, shadowy succession of dreary, lurid and scurrilous libidinous adventures, none of which are pursued to the end”16—not least when each ends and leads to the next in such contrived ways. Just as Bill’s about to have sex with Domino and dishonour his marriage, his wife phones. He then happens to pass Café Sonata where pianist Nick - the college friend he’d had the mis/fortune to meet at the Zieglers’ Christmas party - is playing for one more night. Nick had told Bill he’d be there, but after Bill left Domino’s he seems only to stumble on the café (and the script makes clear this is what he does). At the ball Nick let him on to, a masked Bill happens to look up at a balcony just as two masked figures look down and nod at him. And when he returns uninvited to the site of the ball, within seconds a car has met him at the gate with his written warning.

These in/convenient coincidences give way to unexplained mysteries. Back home from the ball with his tail between his legs, Bill secretes his costume in his office, the camera tracking him all the while—nothing falls out of the Rainbow Fashions bag. By the time he takes the costume back to Milich the mask has gone missing. It returns later that night, found on his pillow next to Alice’s sleeping head (Plink! goes the piano. Plink!). How did it get there? Is its jewel-like placement on the pillow a query from Alice? Or a final warning from the elites at the ball? Or did the mask, as in a dream, put itself there?

The hardest moment, though, for which to find a rational, in-world explanation is Alice’s dream. Laughing as she slept, crying when she wakes, she tells Bill that in the dream they were both naked and afraid; she then had sex with the naval officer she’d told him about, then orgiastic group-sex as she laughed at her naked husband. She dreamed this while or just after he’d been at a masked orgy where he was almost stripped naked and sexually humiliated, and where he’d ended up to avenge her fantasy of sex with the naval officer.

His experience and her dream overlap in time and content near enough you might think she’s psychic (maybe she can shine like Danny Torrance). But we don’t need to invoke the supernatural at the plot level to justify this coincidence. All the justification it needs is the form of the film: it’s a ‘Traumnovelle’, a dream story. So it has to have spooky coincidences and convenient rescues. Not to mention a sleepwalking passivity in its protagonist.

Traditionally it’s not good drama for a protagonist to be as passive as Bill is in the first, ‘night’ half of the film. For one, he never has to try too hard to get what he wants and cheat on Alice (which of course can be read as him not really wanting it); instead opportunities to cheat keep jumping from the water into his lap. Every significant female character propositions him,17 except for Mandy the OD’d model (who only pretends to in order to save him like he saved her). Neither does Bill ever have to decide not to cheat. Fate always intervenes first.

Resolving scene after scene with outside intervention - so not in fact resolving them - is only bad drama if we forget this drama is a dream.18 Specifically the sort of dream where you’re about to wank or fuck till somebody or something disturbs you. (Talk about coitus interruptus.)

You might still prefer to think of these interruptions, for all they chime with our real-world experience of dreams, as nothing more than a plot device. As with digressions or delays, they’re what helped Kubrick draw out his tale longer, replenish our interest, maintain the film’s suspense.

True, Alice’s dream does function as a plot point, as well as point of symmetry. Her telling Bill her fantasy about the naval officer kicked off his jealous rage and the ‘night’ phase of the film. After that night’s nadir, Bill looks ready to wind his cock in. But Alice telling Bill her dream about fucking the naval officer and many others while she laughed at him19 tops his rage back up and kicks off the ‘day’ phase of the film. In it, he’ll chase his leads from the night before, both sexual and maybe criminal, and in either case ending in the same ominous place…

And it’s in the ominous that we find Kubrick’s last and most artful use of dreams. More than a plot device, more even than applying ‘dream logic’ to get from scene to scene, telling his film as a dream was what he needed to impress on us its whole point. Because if Eyes Wide Shut is a dream, who’s dreaming it? Why?

One way to define realist art is that which hides rather than shows its working. The challenge, then, for any realist artist in designing their work well is to become Flaubert’s godlike author: present everywhere and visible nowhere.

In this lies the achievement, the fruitful irony of realist art: that it has a design and meaning at one level, while at another it works on us in such a way we can make-believe everything it portrays is as contingent and undesigned as real life. Hence why if a realist artwork fails we say it was contrived, that in its contrivances we felt the heavy hand of the author, tugging us this way, poking at that, all to make sure we got their point—when real life has none.

Now compare this to dreams. Are they contingent, undesigned—or contrived?

Easiest is to think of them as messages from the supernatural: gods, astral planes, dead ancestors—like our own ancestors used to. This would make dreams as premeditated, designed, as meant as any message. Psychoanalysis dispenses with the supernatural but holds on to meaning: dreams are the return of repressed feelings, a message - albeit garbled - from our subconscious.

For materialists dreams have no meanings but what we read into them when awake (which would make the forebodings of a dream while dreamt more like a nightly simulation of the overdetermined ‘meaningfulness’ of psychosis). At most, it’s in our evolutionary interest to utilise dreams: since we have them and read meaning into them, there’s an advantage in treating dreams as safe practice scenarios. In and of themselves they’re like any other bodily process: self-caused but not designed, with import rather than meaning as such, like running a fever or having an upset stomach.

But Kubrick, a dialectic filmmaker since at least 2001, was wise enough to know that the truth about dreams lay in a synthesis of the oppositions above. Eyes Wide Shut is that synthesis.

Here’s how. While you’re dreaming a dream, you take it literally. Weird as the contents may get, they feel like they’re really happening; that is, they feel contingent, organic (and so, strictly speaking, when we say a waking experience is dream-like we mean like a remembered dream). Hence our strong emotions towards what happens in a dream - the dread, the grief, the lust and so on - stronger than we’d feel if we knew during the dream it was ‘just a dream.’

Lucid dreaming is the usual exception: knowing during a dream it is a dream so feeling and acting accordingly. But we needn’t get into the wild weeds of oneironautics to find a kind of consciousness in dreams already, to find designs on us…

Have you ever had a plot-twist in a dream? Not just a surprise or shock but an impressive rug-pull moment. If the materialists are right and dreams are useful albeit random mental burblings, how is that possible? For a dream to have wrong-footed you, subverted expectations, set up content ahead of time which paid off well and surprisingly (and - typically - unpleasantly) it would’ve had to have premeditated, to have planned ahead: conscious mental states which you were unconscious of. But how can you wow with a magic trick when you’re both the audience and the magician? How do you explain this without returning to the supernatural?

A formalist credo I once made up is ‘There are no coincidences in art.’20 And in dreams? Maybe not either. Maybe a neater way to explain the paradox above would be to treat dreams like realist artworks.

Because what if dreams are contrived, consciously designed— by you: intended21 or meant and therefore meaningful? But designed in such a way that during the dream your intentional design is buried, which is why we react to the dream almost as if it were real. You are the godlike author, present everywhere and visible nowhere.22

With dreams and realist art alike being designed but with the designer palmed away for the duration of the experience, what a suitable marriage of theme and form it was for Kubrick to make a film in a dream-like mode about dreams!

Except he went one step further.

Realist artworks have to submerge their design into the background; that is, they have to ‘naturalise’ their contrivances so the audience can pretend not to notice them, so the author’s busy hand doesn’t show. But Eyes Wide Shut isn’t our dream that we’re wrapped up in. We’re meant to realise it’s a dream at the time, that dreams are the film’s mode. In other words Kubrick no longer had to submerge his designs. It’s a feature, not a bug that we detect behind his film’s supposed naturalness all its artificiality (that we find, for instance, that stabbing two-note Ligeti piano motif so over-the-top). The artificiality, the contrivances, the working ought to be detectable since the dream-medium is the message. Like a dream the film is sending a message: to Bill and to his dream-interpreters, us.

What is that message? In the last scene of Eyes Wide Shut Bill tells Alice “no dream is ever just a dream.” What for the film lies beyond that ‘just’?

Even its lighting gives us a hint. From scene to scene Kubrick alternated blue light and red light: red at the table where Nick tells Bill of the ball; blue in the bedroom during Alice’s dream and Bill’s confession. Red light, blue light, red, blue. This in a faster alternation would be the lights on a police car or an ambulance. Eyes Wide Shut is a 2hr40min-long alarm.

For it’s not only the interruptions to Bill’s encounters during the night-half of the film that we should read as dream-like. When Ziegler tells him, “You’ve been way out of your depth for the last 24 hours”, he is, on the surface, chiding him for his foolhardy ignorance during the day-half of the film; subtextually, though, his line of dialogue implies the events of that day have been as dreamful as the night before.23 In the night and day, Bill got verbal and written warnings from people at the masked ball; these explicit ones are surrounded either side by a more cryptic kind—the muffled warnings we give ourselves in sleep.

So when woman after woman throws herself at Bill, whom he could’ve easily cheated on Alice with had he not been thwarted each time ‘by chance’ (to borrow a psychoanalyst’s scare-quotes) it gives him a second chance. Both in the sense of another shot and a reprieve. Because every time he ignores a reprieve from last night and goes for another shot the day after, he’s warned off by what he’s risking or might’ve risked.

Some risks are obvious - HIV - some can be inferred - the man who stalks Bill on the streets, the “dire consequences” for Bill and his family courtesy of the masked elite - while others have to be interpreted. Like a dream, the film won’t or can’t spell out everything in plain words. By this tack Eyes Wide Shut subscribes to the theory that dreams are your psyche warning you of risks you’ve missed or ignored or repressed because they got in the way of what you think you want, but having to do so tongue-tied; running through your cycle of waking worries with only the nearest props to hand in the junk-shop of your sleeping mind. Hence the stand-ins, the charades, the mummery, the imagery over words.24

Which would mean the ominous atmosphere during Bill’s night-time misadventures, their interruptions, the close calls he learns of the following day are all his legitimate self-preservation talking but talking in code. They’re his own subconscious or dreams stacking his odyssey with roadblocks and hazard signs. “Why would they do that?” as Bill asks Ziegler of the masked elite’s own supposed charade. Ziegler replies, “In plain words, to scare the living shit out of you!”

But there’s another - and more discomforting - theory of dreams to which Eyes Wide Shut may well subscribe.

As we saw above, Marion Nathanson has a blurry resemblance to Bill’s wife, Alice. And so when he, having brooded again on Alice’s fantasy of fucking the naval officer, tries phoning Marion to, we can infer, commit adultery as payback, we might also infer he’s unconsciously just trying to re-bed his wife. (It’s like how his counterpart Fridolin in the Traumnovelle TV-movie thinks he sees under the mask of his alluring saviour at the ball the face of his wife Albertine.25)

Going by this tack, dreams aren’t your anxious psyche broadcasting loud but unclear due to an intrinsic handicap. The obliqueness of dreams might have us assume they talk in code, but that implies an encoding, if not a full-blown motive of secrecy. By who? From whom?

Because what if dreams aren’t warnings struggling to get through to us but are themselves the means by which we hide secrets from ourselves? They’re not even the tracks left by our attempts to hide said secrets which we happen to steal a glimpse on during a dream. The dream is the form of the hiding, is the charade with which we mask what we truly think or feel—not a return of the repressed, the repression. Dreams are spin-doctors masquerading as surrealists. (One cool trick to grasp the cunning of this sort of self-deception, the way we’re all capable of keeping our eyes wide shut, is to take the word ‘ignorance’ and shift its stress a syllable to the right.)

Which would raise the question: what’s the ominous agency behind the dream of Eyes Wide Shut really up to? What’s the truth about himself that Bill’s hiding? Are the warned-of risks merely paper tigers he’s rigged up to scare himself off what he doesn’t want to do anyway, what he’d be doing for the wrong reasons?26

There is a way of reconciling these two apparently opposed theories of dreams. It’s in the film’s title. Because what does it mean anyway, instead of your eyes wide open to have them wide shut?27

Recall that when the sex pope asked Bill for the second password, it was a trick question; Bill didn’t know there wasn’t one. This, on the level of the waking world, is banal: a simple case of him not knowing what he didn’t know. But on the level of the film being figuratively a dream of Bill’s, in which he’s either trying to save himself or hiding secrets from himself, the non-existent password is a case in point of him not knowing what he knows, of pulling the rug on himself, of setting himself up to fail.

Having your ‘eyes wide shut’, then, is to be at once wilfully blind and ignorantly ignorant. At once deceived by yourself for your own sake and not heeding the perfectly rational warnings right in front of your face.

But warnings of what? What is Bill saving himself from or kidding himself about? That either way, with his sexcapades, he’s going to lose his soul if not his body to boot.

10. Dirty money

In Eyes Wide Shut sex outside the marital heteronorm is always some stripe of bodily or spiritual corruption. Even Marion who declares her love for Bill does so in betrayal of her fiancé and comes across more mad than romantic. The way Milich the costumier squeezes his teenage daughter to his side in front of Bill is at once jealously proprietorial and boastful of the quality of the merchandise. And I’m sorry to say the film puts homosexuality in the same murky company. Alongside zombie-like same-sex couples dancing at the masked ball, its sum of LGBT representation comprises the macho frat boys whose homophobia against Bill doth protest gayness too much and the hotel receptionist who teases Bill’s own gay-panic.

Whether these corruptions are paper tigers Bill’s concocted himself to scare himself straight (literally in regards to the homosexuality) or whether they’re legit threats, they render the film a conservative parable for hetero males: adulterous sex is a trapdoor to that old demimonde of faithless women, buggers, incestuous whore-mongering foreigners, venereal disease and occult orgies.

But if it’s conservative it is with a small c. For neither is Eyes Wide Shut a film otherwise on the side of high society, establishment wealth and power—the upper class. That’s because our hero and heroine Bill and Alice are something other than that, something specific, and specifically American.

A maths homework question Alice reads out for her daughter: “Joe has how much more money than Mike?” For advanced study: the Zieglers have how much more money than the Harfords?

The Harfords live in a roomy Manhattan apartment filled with paintings; they listen to a Shostakovich waltz before going out to a party (recalling another waltz Kubrick used in a film, except this time heralding a descent and not ascent). But their apartment is all on one floor, unlike the lofty townhouse they’re going to the party at. Their invite there is “what you get,” Bill says, “for making house calls”, i.e. Bill is the Zieglers’ doctor; Alice meanwhile used to be an art-gallery manager—echt middle-class professions both.

The film goes to some lengths to emphasise the middling of their middle-classness. Alice tells Sandor she’s currently out of work; Ilona Ziegler would never have to justify that. The Harfords do have people who work for them - a babysitter, a secretary - but don’t have staff like the Zieglers do. Or even the Nathonsons, with their live-in maid, Rosa. Like Marion Nathonson, Victor Ziegler knows his staff by name whereas Bill forgets his babysitter’s, Roz. The service-class people below the professional Harfords have names that merge. At least they’ve kept their identities, unlike the faceless prostitutes serving the rich and powerful at the masked ball.

Indeed what exposes Bill’s identity at the ball are such middle-class tells as him taking an admittedly expensive taxi-ride there rather than arriving by his own limo, and him (not so) prudently keeping the receipt from his costume-hire to make sure he gets the deposit back. As big as he spends in the film he’s never blithe about money—one of his first lines is him asking Alice the whereabouts of his wallet.

The film does more than firmly place the Harfords in the middle of the pecking order. It needs to give them another class-shading alongside their relative financial value in order for the import of its parable to land—something to do with their values. This it achieves by contrasting the Harfords, character by character, with a specific social set.

Marion Nathonson is Scandinavian; Sandor the Latin-quoting lothario at the Christmas party is Hungarian; the surname of one of the models there is Windsor (natch); the papa-pimp in his costume shop with its orientalist harem architecture is Russian, his johns Japanese; meanwhile the ball’s sex pope has a plummy English accent. These voluntary libertines (cf. the paid prostitutes) are all Old World. Contrary to the legend that ‘Harford’ is a portmanteau which squishes together the name of everyman Harrison Ford, it might come from Harford county in moneyed Maryland (which, despite its name, is demographically far more Protestant than Catholic). Being defined against all this Old World sensuality, thrown into relief and a tizzy by it, are the Harfords as the comparatively abashable American WASP bourgeoisie.

One reason the Harfords are vulnerable to this sensuality - and the spiritual corruption it brings- is because, while bourgeois, they’re tantalisingly close to upper class wealth. Hence why Gayle and Nuala offer to take Bill to where the rainbow ends: it’s said to end at a pot of gold. When Ziegler thanked Bill for an osteopath he’d recommended, Bill agreed, “He’s the top man in New York,” to which Ziegler replied, “I could tell you that by looking at his bill.” Well-off Bill is also one of the top men in New York, a step away from the heights of wealth and power.28 Or is it only downhill from there?

Having been edged all night - practically gooning in the parlance of our times - his blood is up (and not just that), so he’s gonna get in to the masked ball no matter the price.

And the price sure piles up. Here’s a summary of Bill’s bills:

$150 for no-sex with Domino

$375 for costume hire and mask replacement

$180 for taxi to masked ball

This doesn’t include his other taxi fares, drinks, or the posh patisserie gift for Domino—plausibly by the end of the film his spend is nearing a grand. As Christopher Eccleston says in Shallow Grave: “That’s how much you paid for it, that’s not how much it costs.” And what it costs Bill was hardly worth it; he didn’t get much bang-for-his-buck what with a night and day of no-shows.

Incurring such costs for so little is a mark of his desperation, his indignity—and worse. The more filthy lucre he spends, the filthier he risks getting. The mansion of the masked ball might be far grander than the Harfords’ and Nathansons’ apartments, grander even than the lofty townhouse of the Zieglers, but inverse to that height of wealth is a depth: of moral corruption.

And yet the relation between money and morals in the film is not a linear inverse one; it’s more like a Horseshoe Theory of Vice (with the bourgeoisie safely - for now - ensconced in the iron dip). Granted Bill, ever the bourgeois, thought if he earned and paid enough he could gain entry to where society’s ballers go to ball the sex-worker elite. But it’s not, or not just, money that gets him in there. He needs someone lower down the pecking order.

Bird-named Nick Nightingale and Bill went to the same med school, and both cater to the rich and powerful. But Nick’s position is more obviously servile, being as he is a mere entertainer, somewhere closer to the Zieglers’ bar staff or security staff. Or, for that matter, to the hired women at the ball; he too has come to the big smoke, absent family-ties, to essentially, as he tells Bill, whore out his talents to “anybody, anywhere.”

Despite Bill starting the film socially and financially closer to the rich powerful degenerate world, this doesn’t make him closer to that world’s degeneration. Nick tells Bill he’s “got another gig tonight” before pretending he didn’t mean to sing canary about the orgy. It’s poorer Nick who’s Bill’s gateway drug and not the other way round; Nick the one who, red-underlit, gets Bill into the last circle of sex. In this, he’s Bill’s dark half, his evil twin, the other life Bill could’ve had or might have yet. (Question: when did Old Nick get that now-cliché look of red skin and a pointy box-beard?)

Arguably sex in hetero marriage is a water-carrier for the functional: it’s got a job to do: to reproduce the family. Remove that and sex (says Eyes Wide Shut) always becomes transactional. The sex we see at the masked ball is bought, and not by “just ordinary people” as Ziegler says, but by society’s elite: “If I told you their names I don’t think you’d sleep so well.” By wearing masks, these elite punters and their high-class escorts have removed from the sex that they have together any personality or specificity - it’s mass-produced, one-size-fits-all sex - as well as ensured their anonymity. They are the “strangers in the night” sung about in the ballroom where same-sex couples dance like spectres at the Overlook Hotel.

In fact the shot of one couple using a masked servant as a table to fuck on is not out-of-step with the depraved shenanigans in The Shining (who knows, maybe the oldest at the orgy went to a certain other Christmas party back in 1921…) The creepy costumes, the old mansion, its lighting, the spooky music would fit right in with a horror film, the masked ball a Black Mass. Outside of Bill’s verbal and written warnings, he’s gotten a simpler one from the ball (or he’s fashioned a simpler defence): that extramarital, adulterous sex is a kind of hell.

Yet not a raucous pandemonium either—less a saturnalia than saturnine. The gloomy tone and solemn pace with which the ball is shot gives it and the ballers more the kind of lassitude of those immortal struldbruggs in Gulliver’s Travels: from decadent we’ve gone to decaying.

Which decaying takes us to an obvious next place… The same led to by the threats of violence that moat the ball against trespassers and those who vouch for them. Because this orgy is a menacingly exclusive one—to put it in the polysemic words of the script, “These aren’t people you fuck with.” Seeing as they aren’t, they eject Bill the class-trespasser from the mansion like Barry Lyndon before him (led by actor Leon Vitali to boot, the same who played Lord Bullingdon, the toff who ejected his social-climbing step-father from his ancestral manor). Still, Bill should count himself:

In a time of salubrious kink festivals run by ethically non-monogamous sex nerds, it’s harder to recall the morbid allure orgies once had. With the masked ball sequence and its aftermath the film shares in that mock-horror fascination of the peasant for the depraved sex lives of the aristocracy (it’s why De Sade’s stories with their rapacious judges, pederastic priests and murdered youths sell well). Then again, prurience has always been the other side of puritanism, tabloid titillation of public moral crusades.

But post-MeToo, post-Jeffrey Epstein and the Catholic Church abuse cover-ups surely we have stronger warrant to read Eyes Wide Shut as exposing what’s really been going on at the highest rungs and the lowest bar of the rich and powerful.

Alternatively, is there a way to bypass any correlates with current affairs as well as the historical superstitions about upper-class orgies? To work out how the film is teaching us to read its specific masked ball?

On the one hand you have the note threatening Bill and his family with dire consequences, already addressed to him when he mopes up at the gate; his subsequent stalker on the New York streets; Mandy’s sacrificial or coincidental death; and the incriminating, missing mask which finds its way to his pillow. Taken together these make the secretive elite’s reach and influence feel all-powerful, unbrookable, like the malice in a dream.29 On the other hand, Ziegler fobs Bill off the idea that Mandy was truly a human sacrifice and not just a victim of her self-destructive drug habit, that there’d ever been any genuine malice on the elite’s part, in the film’s longest, protest-too-much of a scene.

ZIEGLER: Everything that happened to you there, the threats, the girls… warnings, the last-minute interventions… Suppose I said all of that was staged, that it was a kind of charade, that it was fake.

But Ziegler’s being infernally tricksy here. Allaying Bill’s worries, he replenishes them; debunking his idea anything criminal took place after the ball, he makes ominous insinuations about the risks Bill’s courting from the people there. No wonder Bill in his billiards room looks knocked dizzy from the ambiguity.

The way Kubrick treated dreams as both urgent warnings and convenient defences, as both natural and contrived can be used as a model for this other ambiguity. Was the masked ball an aristo sex-death cult or just silly one-percenter cosplay? Or was it - and more sinisterly - both?

Bill and we will never know which, never know whether it’d all been theatre or threat. Nor whether he, deep-down, still believes his worst-case scenario or is more than happy to accept Ziegler’s tamer, and less morally obliging, version. It doesn’t matter. Because, either way, adulterous sex’s inherent spiritual corruption, or the staged, fake, charade of the same, is the same clincher for Bill: it sends him back to Alice, crying and confessing, and needing her—only her.

11. Erotica and thanatica

If Eyes Wide Shut’s scare-stories about the spiritual corruption of adulterous sex weren’t enough then the film repeatedly, knellingly warns Bill and the audience that such sex leads to, or is equivalent of, something else. As to what that is, let’s take the ding-dong knells in turn.

The models’ adulterous proposition to married Bill at the Christmas party gets interrupted by a security guard, who escorts him to see married Victor Ziegler, who’d been engaged in some adulterous sex act with another model, Mandy: when Bill attends to her she’s OD’d to the point of an NDE. “You can’t keep doing this,” he warns, alluding to what may and perhaps does happen to her later. DING!

Alice, stirred by her suspicions regarding the above, argues with her husband about women, men and sex, and floats the scenario of a hypothetical female patient getting excited by “handsome Doctor Bill” touching her breasts even though he’s examining them for cancer. DONG! Later we hear that one of his non-hypothetical patients is called Kaminsky, which should knell another kind bell for Kubrick devotees: it’s the name of one of the astronauts who never makes it to Jupiter in 2001. DING!

After their argument has given Alice licence to confess her own brush with infidelity, and at the very moment Bill is birthing his desire to balance the infidelity books, death comes a-calling, literally. DONG! Bill attends to that death at the Nathonson’s apartment, after which, Marion, the just-bereaved daughter, steals a kiss from him with the corpse of her father still warm in the background. DING!

Leaving Marion with her fiancé to sort funeral arrangements, Bill returns to the dead wintry streets where he’s assaulted by frat boys, the sort of close call violence which, should he have retaliated or had he missed the car he slips back onto, could’ve ended terminally for him. DONG! (In the source novel Bill’s counterpart almost demands satisfaction from the student carouser with a duel to the death.)

The mortal risks of extramarital sex don’t go only one-way. Domino, the prostitute Bill almost slept with, has tested (he finds out the next day) positive for HIV, something more fatal in the 90s than now. DING! Though he himself was saved by luck the film doesn’t excuse him from all responsibility in the baton-pass of transmissible venereal disease. With the auto-suggestive power of a dream, he can be read as the cause of Domino’s test results—his infidelity’s domino effect. His attempts to cheat on his wife are figuratively death-dealing (and perhaps literally too, as we’ll find out by the end of the film).

While Bill in the film takes a yellow cab to the masked ball, his counterpart in the novel follows a black carriage that Schnitzler repeatedly likens to a hearse. DONG! The punters at the ball are all clothed (for now) in black cowls. DING! The ball climaxes with Mandy’s offer to take Bill’s place for some unnamed punishment which he and the audience have to consider might be lethal. Especially since he, although let off the hook (for now) thanks to Mandy, still gets an implied death-threat, those “dire consequences” for him and his family. DONG!

To monitor their necessity, a man stalks Bill, or so he worries. Trying to lose his tail, he happens on a newspaper with a spot-on headline that, coming as it does at the end of his curtailed sexcapades, spells out the risk he’s been taking with them all this time, and in page-filling font: ‘Lucky to be alive!’ DING! Newspaper in hand, he slips his stalker, and into an open-all-hours café, but death follows him there too, in the form of what’s playing on the radio inside: that classic café-ambience music, Mozart’s Requiem. DONG!

In the newspaper he reads of the death by overdose of Mandy the model; petite-mort literalised at last as the grande kind. DING! When he goes to see her body at the hospital the receptionist spells out, and so emphasises, Mandy’s surname. This is the second time in the film that someone’s spelled out a name (i.e. an emphasis being emphasised): one of the models spelled hers out too: Nuala, an Irish name, like Mandy’s surname is, Curran. So maybe we should pay attention to names: Curran, for example, means hero or dagger—a hero to Bill; a dagger to herself. DONG! Or was she? When Bill debates the cause of her death with Ziegler, the film links his voyeurism, her sexuality and her death via the pause Tom Cruise makes in the middle of his line “I saw her body. In the morgue.”

That’s the one lethal risk fulfilled by Bill, the one cost incurred not just symbolically, in fantasy-life, on a dream-level but in cold hard reality: the death of Mandy, whether murder or mishap. Because had he stayed home she either wouldn’t have needed to ritually sacrifice her life for him at worst, or at best would’ve experienced a different chain of events that night which might’ve forked her away from her accidental drug death, for now at least. Either way she paid Bill’s price. Why else does he cry so much over her body? Look what he’s done.

Remember Helena Harford’s maths homework problem? Alice coaches her daughter towards its answer with words we can apply to the film’s central theme: “So, is it going to be a subtraction or addition?”

Which of those is sex?

If it’s extramarital and/or adulterous then the answer for the film seems to be subtraction. That’s what Bill has been warned of by all the dream-logic ‘coincidences’ and convenient interruptions, all the pairings of those bosom buddies, Eros and Thanatos: sex outside of procreative marriage is corrupt, transactional, moribund, anti-life. It subtracts life, figuratively and literally. Not just masturbation is the sin of Onan: all sex outside of procreative marriage is wasted seed, abortion-before-the-fact. That any of Bill’s adulterous encounters could’ve, had they been consummated, led to pregnancies and babies in biological reality makes zero difference, not to the meaning of the film. Taken as part of an artwork and not real life, all the heterodox sex portrayed by the film points tomb-wards and not womb-wards.

Eyes Wide Shut’s warning to Bill isn’t that infidelity guarantees death (only Mandy dies by the end, and, in theory, more from her vice of drugs than sex). Rather that death, spiritual and physical, is either what he rightly learns to fear from infidelity (contra to his morgue-voyeurism, he becomes a necrophobiac) or it’s his psychological defence for why he returns to his wife; and this fear or defence then back-engineer all his failed consummations, all the un/lucky curtailments. This is a perfect mirror of the way dreams so often fail to simulate sex richly or lastingly, and instead, as if seeking an in-dream excuse for that failure, and trying to keep the dream going nonetheless and stop you from waking up, interject some threat or disturbance as that failure’s retroactive cause.

But if extramarital, adulterous sex stands for death, then what might its inverse stand for? And why is it therefore so apt the film be set exactly when it is?

12. On the last day of Christmas my true love gave to me, sex as the prize/price of fidelity

The foreground pattern of Eyes Wide Shut consists of Bill’s night-time botched opportunities for sex outside of marriage, his pursuit the next day of the same, and the risks he believes or wants to believe he’s taking by doing so. In the background but just as pervasive, and hence presumably up to something as well, is another, if homelier motif.

During the first scene of the film, the Harfords’ daughter Helena asks whether she can stay up to watch The Nutcracker on TV, a ballet set on a certain eve below a certain tree. Later she watches on TV Bugs Bunny reading ‘A Visit from St. Nicholas’. Then in the final scene of the film she roves a toyshop where we can hear a muzak version of Jingle Bells.

On the off-chance we miss these pop-culture mediated signs of the holiday season there’s a more familiar and much more eye-catching kind:

All but a single, and significant, interior location in the film displays a Christmas tree. To ensure we pay them mind, Kubrick made a point of having Bill compliment Domino’s. But the source novel is set at Mardi Gras, that is in February/March. So it was a conscious decision for Kubrick and screenwriter Frederic Raphael to shift the film’s time-frame from the end of winter to mid-. For what reason?

Was it to ironically contrast the wholesome trappings of Christmas with the erotic goings-on of the plot, an irreverent tarnishing, like dressing up as a sexy Santa?

If so you’d have expected a more substantive portrayal of traditional Christmas values before they were undercut: the goodwill to all men, comfort eating against the cold dark, Baby Jesus and so on. Like how Dickens set Scrooge’s miserliness and scorn for his fellow man against the do-gooder chuggers at his office and his nephew’s dogged festive cheer. But despite its Christmas trappings, Eyes Wide Shut portrays so little actual festive cheer, even ironically, that there’s no surprise that few have regarded it as a Christmas movie until recently.

Perhaps since Christmas comes in bleak midwinter, when everything is lifeless and cold, the point of setting the story then is to amplify the film’s greater death theme. This theory isn’t right either but is useful.

We get a better idea of what Kubrick might’ve been up to when we consider the technique of throwing into sharp relief. Having learnt what’s signified by the extramarital sex in the film’s foreground, we can work out from this ying the shape of the yang: what’s signified by the Christmas in the film’s background.

Because, in modern times, when are the two occasions we display wreaths? Funerals and Christmas. If, as far as the film’s concerned, extramarital sex is deathly then marital sex must be on the side of life. Which would motivate the film’s setting during a festival that comes after the winter solstice, at the turn of the tide, the rallying of light and life—celebrated with trees that are evergreen.

So it makes all the more sense that the break in the film’s pattern of every interior having a tree is at the masked ball (that the ball, in the words of Jez from Peep Show, wasn’t very Christmassy). Not only is it a perversion of a wedding but of a Christmas party, an eviler twin to the glitzy one at the Zieglers’ towards the film’s start.

What does it mean, though, to say the film puts marital sex on the side of ‘life’—isn’t that a bit generic? Specifically, then, (if subtly) the film works into its pattern the theme of the sexual reproduction of human life as husbanded by the institutions of marriage and family.

It all begins at the Zieglers’ Christmas party, when Sandor the Hungarian talks to Alice, perhaps more appropriately than it first seems, about virginity—what he argues marriage was once useful for, for getting out the way. It crops up again when the frat boys yell at her husband, “Merry Christmas, Mary!”—beyond their homophobia, a reference to that other Mary, the Virgin Mother.30

In the normal run of things the loss of female virginity is preceded by another change. A little after his Thoughts on Marriage, Sandor asks Alice, “Do you like the period?” It’s as though he’s asking how she likes being menstrual, being a pregnable woman.

Around the same time, Bill is looking after the overdosed Mandy in Ziegler’s bathroom, her reclining pose mirrored in a painting above (linking us back to Alice, who used to manage an art gallery), both Mandy and the figure in the painting nude but the one in the artwork (i.e. the representative one) pregnant. In Sandor’s question about periods he literally meant the artistic one of the sculptures the Zieglers own and he was trying to get Alice to come see (as a pretext for an adulterous encounter). That period happens to be the Renaissance. From virginity, menstruation, pregnancy to (re)birth.

Even in the Other Man whom Alice fantasised about committing adultery with there’s a hint of birth: Kubrick deliberately changed his job-title from the source novel’s military officer to a naval, read navel officer. (Another name for an umbilical-cutting midwife could be ‘navel officer’...)

To really slam on the chords of this theme, the film closes at a toyshop with not just the Harfords’ child but children everywhere. Still unsure? Helena asks her parents whether she can get a pram for her baby doll; after all, the trees that forest the film signify a baby too, Christmas being among other things someone’s birthday.31 Its central image is a baby in a makeshift crib in front of his postnatal mother (step-dad somewhere farther behind). The Nativity is what makes Christmas a heteronormativity festival.

Hang on: God-the-Father didn’t sire a child by a human woman through the vigour of His Holy Spirit, Zeus-style. He incarnated inside the womb of an immaculately conceived and virginal Mary. (She’s not God-the-Son’s biological mother but His surrogate, and not for God-the-Zygote but God-the-Cell-Meiosis.) So how can Christmas be a heteronormativity festival when it commemorates the anomalous virgin birth of a baby engendered without sin or sex? If anything it’s anti-sex.

But for a Christian the closest you ever get to being without original sin yourself and giving virgin birth is to never have sex before marriage, then get married and never have sex outside of it, and have it primarily for the sake of reinforcing the martial bond, perpetuating the family unit and producing a baby. Sex is all right so long as it’s the least bad sex.

In this light we can see why the filmmakers chose to put Alice out of work. By depicting her as formerly instead of gainfully employed (as someone of her middle-class would likely be) or as always having been a home-maker like her counterpart is in the source novel, that is by characterising her through a transition, the filmmakers spot-lit their choice: Alice’s resumption of a homemaker or housewife role. No, they weren’t anticipating the current trad-wife ‘trend’. They were just drawing the lines more clearly of the film’s central opposition: the home and hearth versus the scary world out there of non-marital sex.

The home-hearth theme also stands in opposition to the refrain of death in the film, which Bill won’t refrain from sounding with his many attempts to stray. In the opening scene his daughter Helena asked for a puppy for Christmas, arguing it could be a guard dog, as if she sensed their hetero wedlocked family unit, the life it harbours and maintains, would soon need protection.

That’s why the nadir of Bill’s misadventures, the masked ball, had to be presented the way it was, with its temple architecture, incense, the priest-like officiant and the pairings-up: a church wedding turned on its head, inverted, perverted. When Bill asked the officiant what would happen to Mandy for taking his place, the next line of dialogue sealed the idea of the ball being a dysphemism for marriage: the officiant told him whatever happens will be binding: “When a promise has been made here, there is no turning back”—the same that’s expected of marriage vows.

This styling of the ball was another deliberate change on the filmmakers’ part: in the source novel, everyone there is costumed as monks or nuns, the usual cynical profaning of Christianity you get in De Sade (or a Tarts & Vicars party). Kubrick got rid of that and so better underlined the ball’s role in the moral of his film. His masked ball is a mockery of heterosexual marriage, in that it ceremonially joins not one pair but many partners, not for life but one night, to have anonymous sex for pleasure (and power and money) and not for family and kids.

And if that acme of extramarital sex was a perversion of marriage, so are all the other deviations from the heternorm we get in the film. In the dim light of their grim alternatives, they warn the audience that sex is an animal instinct and evolutionary function that’s best managed through marriage, kids— family.

For all it gets billed, then, as an erotic thriller or high-class blue movie, for all its constituency these days is art-house pervs, Eyes Wide Shut is - structurally, formally, forcefully - a pro-family-values film. It’s a parable about the monsters that lurk mere inches off-shore from the marital harbour. A Christmas ghost story wives tell their husbands (or husbands tell themselves): ‘Dishonour our marriage and the Id’ll get ya!’ A moral of the ilk you’d get from the crudest conservative scare-story but cleverly disguised, made palatable by Kubrick’s artfulness. And so when Helena in the toyshop picked a pram for a baby doll - that is, an idealised baby - and her mum told her it was “old-fashioned”, the line can be read not as a censure but affirmation of how august Helena’s choice is. It has pedigree.

One note about that clever disguising of Kubrick’s. Like all the greats, he was sure to loop reversals and counterpoints into his main points. For there’s a worldly ambivalence to the film’s pro-family theme: Helena’s choice of a pram for her baby doll is old-fashioned; and next she asks for a Barbie doll, a choice which glows darker once you learn of Kubrick’s stipulation for the body-type of the women at the masked orgy: ‘Barbie dolls.’

Is that body-type an ideal or caricature of a sexually mature woman? Is a baby doll an idealised or a caricatured baby? Why else were these quibbles raised in a toyshop? As in Kubrick’s script for A.I. Artificial Intelligence, with its character Professor Hobby who immaturely toys with the real or artificial lives of others, the toyshop in Eyes Wide Shut might be a sly dig at what would come to be known as heteronormativity: isn’t it all a bit childish? Co-opted? Cynically mass-produced?

A stronger quibble with any pro-family-values theme has to be the costumier Milich, whose family is prostitution in disguise. But with him the film wasn’t making the old rad-fem point - “Where there’s marriage, there is always prostitution” in Angela Carter’s words - but the Freudian point, that marriage is a necessary sublimation, not least of the Milichs of the world. Because as well as pro-family the film is pro-civilisation. Civilisation as something you have to put on, like a costume, like the Shostakovich waltz at the film’s start: socially constructed things but with a set form. Because what set form is missing from Milich the father and his child, such that his family can’t in fact be taken as emblematic? The traditional completion of that triad, a mother. Something only completed in their family’s light-side parallel, the Harfords: Bill, Alice and Helena—the same family Bill put at such risk.

By returning him safely to his wife and daughter, the film counters as well the Sandors and Marion Nathonsons of the world. For the Hungarian lothario, marriage was a means to an end, a licence to do what you want with other partners; whereas for lovelorn fiancée Marion it was a loss of the partner she truly wanted. Bill and Alice’s marriage might’ve grazed the rocks during the film but it didn’t founder either on libertine cynicism or on romantic tragedy. As such, it’s still exemplary. Not in the sense of an ideal but a teachable example.

Alice trying to help Helena with her maths homework asked, “So, is it going to be a subtraction or addition?” Again, which of those is sex?

For the film it would seem to be addition so long as it’s marital sex, leading traditionally as that does to a family. But in fact marital sex is addition and subtraction. Two people are added in matrimony and in doing so subtract all other possible partners out of the equation but in doing so gain family, continuity: they enter the ancient, ongoing flow of life (hereditary life that is, as opposed to just feeding the worms). The alternative - that sex of indefinite additions we’ve seen all night and day in Eyes Wide Shut - gains you nothing but spiritual corruption, physical violence, death: the anti-life.

With this in mind, the film’s ending is a defeat of Victor Ziegler too and all he stands for: that deleterious, anti-life sex for which he’s ambassador. The Ziegler who refers to Nick Nightingale’s wife as ‘Mrs Nick’, harking back to the time when women lost names to their husband’s (‘Mr and Mrs Victor Ziegler request your presence at…’). Nick himself is not the lucky man-about-town or gentleman of leisure he might seem but inferior to Bill. Unlike Bill, he left Mrs Nick and the kids somewhere far behind to go where the money is for his work; in this he’s a platonic-anti-ideal of the Absent Husband and Father which Bill only experimented with being for one night. And yet with such close-call if not dire consequence. But thanks to those close calls, Ziegler, Sandor, Milich - all these older men - are none whom Bill will any longer envy, aspire to be, end up as. He’s home dry.

What’s the prize of his eventual fidelity? What has he rescued from the jaws of marital defeat?

The answer can be found in the film’s famous, horny, monosyllabic last line: Alice telling Bill what they need to do ASAP: “Fuck.” She tells him this while he’s wearing a red jumper. Yeah yeah, we know Coca Cola invented the red look of Santa; nevertheless we can discount ugly Christmas jumper fashions as the reason for his choice in clothes, not least when he and his wife in the scene are surrounded by kids. It’s the red of sexual passion which ran throughout the film restored to its proper, pro-family place. Because why play the field in a rage when you’ve got a spouse at home who’s never looked hotter, has manifestly got a wild side, and has already given you a kid? For that’s what’s really being augured by the film’s last line. To put it in terms of the subtitle to Beethoven’s opera Fidelio (which provided more than a password for the masked ball): ‘The Triumph of Marital Love.’

With that triumph, though, that prize comes a price.

Alice twice refused infidelity. First, she was saved by fate when the naval officer she fancied disappeared, a close call about which she was ultimately relieved. The second time, she chose to turn down the otherwise not-unattractive Sandor. Her refused temptation is active fidelity.

Whereas, while Bill didn’t cheat on Alice - not all the way, discounting the stolen and bought kisses - even his failed infidelity is, for the film, as bad as the real thing (so conservative is Eyes Wide Shut it’s positively Biblical: if you’ve thought it, you’ve done it.) Which is why he had to receive the wages of jealousy, be put through the psychosexual ringer. He didn’t fuck around and found out.

Alongside that price, he and his wife have to pay a subtler, more consistent one. Alice concludes the things that happened in the story matter “whether they were real” - meaning his real-world, curtailed encounters - “or a dream” - meaning her sexual fantasy and her actual dream. The counter to this is Bill’s, his warning that: “No dream is ever just a dream.”