Who but the most reactionary would pop a monocle these days at a black Lear or a female Prospero? Shakespeare plays have been performed so often, in so many milieus - from Ethan Hawke’s Gen-X Hamlet to Missouri Williams’ King Lear with Sheep (which starred sheep) - their characters and plots so familiar that they’re not really plays any more. They’re a world of their own more than a description of ours, like Renaissance Fairs, say, or Christmas pantomimes. As such they ought to be especially amenable to colour- or whatever-blind casting; if Lee from boyband Blue can play Aladdin, we can manage a brown Brutus. Neither do you need your no-tie English teacher to point out that, seeing as all Shakespearean actors were once white guys whether the play was Othello or The Taming of the Shrew, it’s fair enough those parts and more are now reversed.

Other times the casting can’t go so unremarked. It’d be fair enough for any minimally attentive audience to assume that a race-swapped Othello, a gender-swapped Taming of the Shrew was up to something since those plays are known for dealing with race and gender. A sensitive director would account for this, invert certain lines, cut others—in fact shift everything else in their production so that this particular artistic choice paid off as planned. If instead the director suggested that querying such casting was irrelevant or even suspect, it’d now be fair enough to assume they were a numpty or worse.

So why treat film and TV directors any differently?

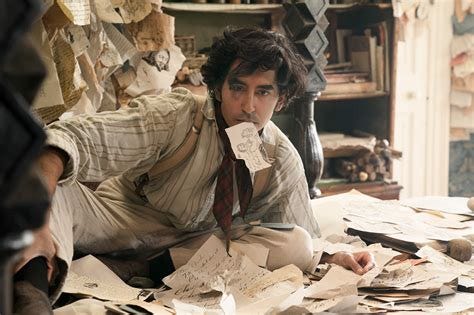

On the promo circuit for The Personal History of David Copperfield, Armando Iannucci and co. had to keep fielding questions about the casting of Dev Patel in the title role (and by implication African and Asian heritage actors like Rosalind Eleazar and Benedict Wong). The answers ranged from wanting the film to have a modern feel, or 19th century London being more variegated than supposed, or them simply casting the most talented actors for the part. At the festival premiere Iannucci was blunter: he didn’t think the question was relevant.

He needn’t have been so defensive. The question was already answered by the way he’d told his story.

The news Charles Dickens brought to his Victorian readership about the sootier sides of life, his well-researched, layered and precise descriptions, his prosiness, have led some to misapprehend his novels and stories as realist. But for all their reportage they have moments like when David Copperfield sees London decked out in the name of his beloved Dora, or the death by spontaneous1 combustion in Bleak House. Dickens was a showman - not least on his reading tours - stylised, contrived, artificial in the old sense of the word: of great artifice.

No dumbass, Iannucci knows this aspect of Dickens is the most important to get across in any fresh adaptation. Which is why his film’s not a period drama as we know it, all chamber music and muddy luvvies. It’s a Dickens reading in cinematic form, with in-camera special effects like ‘Pepper’s ghosts’, Gilliam-esque animated hands, handwritten titles, fast-motion sequences à la A Clockwork Orange, snazzy transitions like the last image of one scene becoming the dropped curtain before the next. If such a film had been cast with period drama stalwarts (white people) it would’ve felt like a missed trick.

I appreciate Iannucci might not want to defend casting Patel on the basis the story’s not realistic (let alone want to defend it full stop) as if only through the stylised or the absurd can we allow non-white faces into adaptations of canon literature. But the non-realist design is why the casting works (it’s one of the funnest parts of the film). It’s demanded by the film’s artistic vision, which an all-white cast would’ve made incoherent.2

The other, worthier but at least coherent way to feature non-white actors in your literary adaptations or historical dramas is the ‘unsung hero’ approach. Films about Guadeloupean violinists, Chinese cowboys, mixed-race gentlewomen are made to correct the whitewashed record. They educate their audience about lost histories; show how the West in the past had more narratogenic non-white-men in it than you might’ve thought.

Few are good. But for every Belle or The Chevalier there’s a Harlem Nights and Daughters of the Dust. And what you can at least grant these films is that their casting choices make legible sense to the audience—as with Iannucci’s but from an opposite angle. Here the casting is not colour-blind but representative, with the actors’ races matching that of their roles’. Hence why it’d be legit for an audience to feel weird about a biopic of Britain’s first Indian doctor that had a white guy as the lead. (Be funny though.)

But whether a period drama is told in this second mode of educational, ‘higher def realism’ or in a non-realist mode, it has to make clear which. It can’t be both without confusing the audience, if not accusing them as well…

Recent film Wicked Little Letters seems to belong in the Iannucci camp, with its swear-wordy dialogue3 and comic actors like Joanna Scanlan from The Thick of It. It treats as a comedy the true story of a poison-pen letter campaign, godly Edith (Olivia Colman) the recipient, bawdy neighbour Rose (Jessie Buckley) the suspect. Investigating the crime, which took place in a seaside English town in the 1920s, is policewoman Gladys, played by Singapore-Indian Anjana Vasan; meanwhile Rose’s live-in boyfriend is played by British-Jamaican Malachi Kirby; the extras who play their village neighbours are multiracial; there’s even a black judge.

The film gives no hint we’re meant to read this casting as another revelation of surprising diversity in a historical period which our biased education had made us ignorant of, as with Hidden Figures or Red Tails. So it must be using colour-blind casting, as with David Copperfield or one of those campy commodities like Bridgerton4, reality set to panto.

Not that this bars a film from Dealing With The Issues. Gladys, Edith and Rose each struggle in their own way against sexism among other prejudices held by men (and women because of the men) in England in the 1920s. Men like Edith’s father, played by Timothy Spall like some demon-dad out of D H Lawrence, ranting about God and pansies; or like Gladys’s colleagues who keep nicking her ideas and policemansplaining her.

There’s no contradiction here (not here anyway); the wellspring joke in Western spoof Blazing Saddles is that the job of sheriff in an all-white frontier town has gone to a black guy (in the hope he’ll scare away the townsfolk where a railroad is planned). This high concept didn’t hamper but facilitated the film’s teasing, and teasing out, of ’70s American racial tangles. With Wicked Little Letters the contradictions lurk elsewhere.

The film certainly got the intersectional memo: as well as sexism, Rose has to acquit herself against xenophobia, her Irishness cited as evidence she wields the poison pen by her neighbours and later by a barrister. And yet, though brown Gladys and Rose’s black boyfriend are mistreated by white characters, it’s never because they’re brown and black. No one addresses their race, and it’s unclear whether the audience is even meant to see race in the story (call it colour-blind viewing). If we had been meant to, the implication would be that 1920s suburban England was forward-thinking enough to have a black judge, a brown policewoman (Nicholas Angel: “Police officer”) and an unremarked-upon unmarried interracial couple, but for all that remained backwards on sexism.

But since we’re not meant to be seeing race then what’s going on with Gladys’s family members? Taken off the case, she turns to them and to female acquaintances for help. If her race isn’t real within the story, her family could be played by any race. But her niece is brown too, implying that the family-line is genetically South Asian. (Note that Gladys’s policeman dad is repeatedly mentioned but never depicted, another cop-out)

And if we’re not meant to be seeing race, why is Rose persecuted for being Irish? Back then in England the Irish weren’t white yet (neither were most Southern or Eastern Europeans)—‘white’ meant Anglo-Saxon. They got whitened the more that black and brown immigration increased. Which means the neighbours’ and, later, the barrister’s suspicion of Rose wouldn’t have only been xenophobia like Brits at the time had for Germans (the film’s set post-WWI) but racism. So why only that racism? To put it another, harsher way: there’s no racism in the world of the story except that against a white woman.

Ambiguity is the sign of real art, so goes the received wisdom. But this isn’t ambiguous, it’s pointlessly muddling. And worse is the muddle’s unintended (?) consequence.

Because of the filmmakers’ cackhandedness or unwillingness at working out the storytelling implications of their casting choices, the audience is left having to ask, ‘What’s that black man or this brown woman in the story for?’ We weren’t meant to be seeing their race but now see nothing else. We fixate on it, question it, are thrown by it—all for that matter like a racist.

Now I’m not arguing colour-blind casting makes anybody racist. This isn’t one of those three-hour Youtube manifestos on how I was sent crying to the alt-right because Star Wars had a black stormtrooper5. I don’t mean become a racist but think with content and logic that parallel a racist’s. To which the filmmakers’ defence can always be to judo-flip the dissonance they’ve caused back onto the audience as an accusation: ‘We were colour-blind, we didn’t even notice or care about race in the story. You certainly do! Hmm I wonder why, why’s it bother you so much?’ An inane defence which becomes accidentally true only through their bad faith.

Which is ironic for Wicked Little Letters, because by invisibilising all characters’ races apart from Irishness, the film panders to its target audience, implying the core prejudice is that against women in the Rose-demo. For she’s been parachuted into the story from the 21st century as that fave audience stand-in: a hot mess with a heart of gold. She’s sweary, she’s secular (unimpressed by church, scoffing at churchmen); she’s free-drinking and -loving without the class cushion that such would need as a minimum to be as harmless as the film - barring the judginess of certain stuffed shirt characters - depicts.

This leads to the film’s bankrupt ending, after we’ve learnt Edith was the one sending the foul-mouthed letters to her own family address. You can guess the twist from the story’s set-up (since Rose always denied the accusation of Edith and family, the only other solution with a small cast of characters is that the letters are coming from inside the house). When Gladys cracks this case, the film shows the most safely lampooned characters, the white male cops, claiming they’d known all along. The audience guessing the twist, then, not a sign that the filmmakers’ couldn’t sustain a mystery but aligning us with the under-appreciators of Gladys.

Edith is put away in a police van, and at that nadir she finally tells her dream-stomping dad to fuck off: the climactic uptick of her narrative arc. Which chimes with the trial victory of Rose, who meets Edith outside the court-room: Edith promises to write her from prison, and a smirking Rose quips, “I’ll brace myself.” But Rose never saw Edith, a lifelong victim of bullying, tell her dad to fuck off (is she psychic?). And had Edith gotten away with it all, Rose would’ve gone to prison and her young daughter been put into care (that is, into a 1920s English care home). Even so, as they’re both victims, they close on this figurative handshake of mutual respect.6

In films, diegetic music and sound are those whose source we can see or infer as existing in the world of the story: a gramophone playing a record, a clip-clopping coconut for a Monty Python horse. Non-diegetic music is a film’s score, unheard by the characters (or not); while non-diegetic sound is things like a voice-over, laugh-track or a slapstick boink.

Filmmakers can play with this. The Shostakovich waltz that scores the opening of Eyes Wide Shut stops when Tom Cruise turns off his hi-fi. In the first episode of The League of Gentlemen the letter Reece Shearsmith seems to hear in his head in the sender’s voice turns out to be a nosy neighbour reading it out loud. In both cases the storytellers knew what they were doing.

Those behind Wicked Little Letters don’t, or don’t care, or are muddled whether they’re using race as diegetic or non-diegetic: as something the audience is meant to read as existing in the world of the story as well as on-screen, or is a part of a wider, non-realist aesthetic.

If I seem OTT laying into such a picayune movie, know its lack of rigour is everywhere. Take Lady Macbeth, a racially-charged version of a Lady Chatterley-style affair in 19th century North East England, in which no one mentions race. Not of the farmhand lover (Cosmo Jarvis, actually Armenian-American but made-up to look biracial); or of the darker-skinned maid who’s abused by him and his white lady (Florence Pugh, accent made-up to sound Geordie) and who rats them out; or of the illegitimate kid who might threaten the lady’s claim on her estate (she’ll murder said kid, but at least she doesn’t dispute his claim through racism).

Or take the TV re-adaptation of David Nichols’ novel One Day, which cast British Indian Ambika Mod as one ‘Emma Morley’, lover of posh boy Dex, even though, as pointed out by Chitra Ramaswamy for the Guardian:

white boys like Dex didn’t fancy brown girls like Em. I know because I was one... In the first few episodes, the unmentionability of Emma’s race got to me. The truth is, Dex (and his parents) would have made unintentionally racist blunders.

(Ramaswamy has her own unmentionable: that the parents of a brown Em in the 1980s wouldn’t likely have taken their daughter’s romance with white Dex in their stride either.)

Then there’s Oppenheimer, in which Mr. Meticulous Christopher Nolan depicts black women at CalTech, which had none till the 1970s, and UC Berkeley which had a number in the 1940s but not in physics; and also black people at Los Alamos, the one site of the Manhattan Project where there weren’t any. My point isn’t that none could’ve gotten there on merit. To idiot/mischief-proof what I mean, I get that their absence in reality was down to racial, sexual, economic bias. The question is, since they weren’t there yet in reality, how are we to read their premature inclusion in the film?

Since the audience knows that in reality there was more sexism and racism than is implied by this otherwise realist biopic, either it creates a dissonance - Wait, what storytelling mode is this film actually in? - or, while the audience might know that the U.S. in the 40s had more sexism and racism than the film implies, we feel this wasn’t the case, since in films you feel only towards what you’re shown. In which case might not the casting work as a way for the film to whitewash the nation about to be shown committing nuclear genocide against a bunch of foreigners?

Yet I’m still not arraigning the political hygiene of these films and TV shows so much as their artistic thoroughness. (Although, seeing as the filmmakers started it, I think it’s worth pointing out that Wicked Little Letters had a white director, screenwriter and casting director; ditto Lady Macbeth.) As for the non-white actors and extras, I don’t begrudge anyone for taking a role; ‘Just glad to be working!’ is after all the actors’ marching song.7 But at what cost?

When the people behind the camera use surface-level diversity incoherently, the people in front of it get more and more associated with that incoherence. Or to put it less dryly, with badly designed art (AKA bad art).

And of all the ways an artwork can be problematic, that’s the most relevant and worst.

Thematically not spontaneous.

See recent comedies like the film Seize Them! with its Princess Bridal aspirations, or the TV show My Lady Jane, which reimagines Jane Grey, the Nine Days’ Queen and executed precursor to Mary I, as a sexually liberated kick-ass heroine. (Buh.) In both cases, an all-white cast would’ve clashed with the high-concept aesthetic.

Swearing of the sort middle-aged pop academics tweet in the belief Donald Trump reads all his own @s.

Bridgerton in fact has it both ways. With its multiracial cast not relegated to servant / slave / foreigner roles but among the toffs, the show seemed at first to be set in panto reality; but then it built its casting into the story on the race-science-adjacent rumour that the historical Queen Charlotte had African ancestry, putting mixed-race Golda Rosheuvel in the role and pivoting into alternate history: Rosheuvel was meant to be read as she looked, Charlotte’s marriage to George III heralding a new post-racial age and a diverse aristocracy for 18th century Britain. (The media class liberal dream come true, social problems solved top-down by the creation of a diversified elite.) Awkwardly, if Bridgerton’s alternate history tracks the real one in other respects then slavery is still legal at the time of the story.

Wait—when you put it like that.

In real life, ‘Edith’ conducted her hoax poison-pen letter campaign after the sister of ‘Rose’ slept with her husband. Such a story wouldn’t be the uplifting one the filmmakers manage to strain out of historical events. But it’s qualitatively more interesting: sibling rivalry! Jealousy! Self-righteous moralising as a cover for petit-bourgeois spite!

The strongest argument for representation has always been that of economic reparation: it shouldn’t be any harder for you to get work in TV, film or theatre because of your identity markers than in other jobs; and that’s a deficit that deserves balancing. From then on, all that can (with any dignity) matter is talent.