The 2000s were not a great decade for Hollywood. Many major filmmakers had a wobble, or worse, they entered a terminal decline, as though the whole of American culture was shook. (What shook it? Rhymes with final heaven.)

Even, or especially, the Coen brothers. Empire magazine’s repeated encomium used to be they’d never made a bad film. Till the 2000s their only real flop with mixed reviews was The Hudsucker Proxy—now highly reappraised: it “looks better and smarter every year.” In fact the late 90s was their critical moment in the sun, with the one-two of Fargo and The Big Lebowski, each a culmination of a mode from their previous work: regional noir and the silly sublime. Then, starting with 2003’s Intolerable Cruelty, the sun dims.

True, No Country for Old Men won them Best Picture, Director and Adapted Screenplay at the Oscars in 2007. But coming after The Ladykillers and before Burn After Reading, it’s like the esteem for No Country is the droplet heaved into the air by the troughs in the water either side. (I myself think Burn After Reading is by no means a gurn too far but a ripe send-up of national-security pretension; and as for No Country I can still remember the whoosh of air going out of the cinema at the end credits, and still can’t tell whether the 30 minutes before had winded us by being so unconventional or a kick in the gut.)

The Coen brothers rounded out the decade with 2009’s A Serious Man, which also had its big-time detractors. Here’s Will Self for The Guardian calling it “a career-finisher for a tyro writer-director”, one which though “widely feted” was “wifely awful”:

Halfway through the film I asked my wife what she thought of it and she replied “Awful”. I demurred: “It’s pretty dreadful . . .”, and she shot back: “In what precise way does that differ from ‘awful’?” I set down this exchange because I think it encapsulates a lot of what has enabled the Coens to continue to ride high in popular estimation… which is that they are insistently likeable film-makers. Their likability is such – and is projected in such a canny way through their nebbish male characters, and resourceful female ones – that it seems like a solecism to criticise them too strenuously.

What might a fair-minded criticism of A Serious Man look like?—one as strenuous as Self calls for while not providing any such; his criticism is the philistine one that the film has “a feeling of being refracted rather than [an] immediate experience” and that “the Coens’ central problem [is] their reflexivity as directors, making films of films rather than films tout court.” But wtf is ‘just’ a film?

The obvious refraction or reflexion with A Serious Man is the Book of Job, shifted to 1967 and concerning the Coens’ ultimate nebbish male character, the Jewish professor Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg). What with Larry’s health-scares, divorce, wayward kids, blackmail threats, racist neighbour, suppurating brother, his story is in the genre of a ‘series of misfortunes’. As such it risks arbitrariness, as anyone can attest who’s ever played the fortunately/unfortunately storytelling game (fortunately a bag of money falls on him! unfortunately he has a cerebral hematoma!). Another risk is that the story won’t add up to more than itself, i.e. it’s a shaggy-dog story where there’s no wider meaning to the misfortunes.

The Coens anticipate the latter criticism within the film by having a rabbi tell an actual shaggy-dog story, ‘The one with the goy’s teeth.’ Even so both criticisms have teeth of their own. For one, the Coens pair Larry with a succession of other quirky characters without it being clear why. There’s his woeful brother Arthur, played by Richard ‘national treasure’ Kind. Then Fred Melamed playing Sy Abelman, Larry’s highfalutin quasi-cuckolder. (At Larry’s suggestion Sy might as well move in with his divorce-suing wife, Melamed gives the immortal line reading, “Larry, you are jesting”). Then there’s Clive (David Kang), a Korean student who may or may not have tried to bribe Larry over a failing grade.

In particular the film pairs Larry with his son Danny (Aaron Wolff). Don’t take that to mean father and son share much drama. Rather the Coens make parallels: they cut at the film’s start between an ear-canal’s-view of Larry at the doctors and Danny listening to rock music on his earphones; and at the film’s end between Larry facing an ethical dilemma over the phone and Danny facing down a tornado. (The film is set in the Midwest.) But if the meaning of this association of images is a ‘sins of the father’ one - that Larry’s ethical failures will doom his son to misfortunes next - then why not form the film primarily around their relationship? Why all the other pairings?

As for the other criticism, the film may well seem a grab-bag of arbitrary detours on first watch. There’s the above-mentioned story about the goy’s teeth, in which a dentist is sent on a Kabbalist but ultimately quixotic quest after finding Hebrew letters on the back of a patient’s incisors that spell out ‘Save me’. In the middle of the film there’s a profane retelling of David and Bathsheba, with Larry spying on his sultry sunbathing neighbour while he fixes the TV aerial.1 And at the start there’s a prologue in Yiddish, about an old man who may-or-may-not be a dybbuk pitting a husband and wife against each other, a story without a clear relation to the rest of the film bar its Jewishness.

And yet for all this I myself think A Serious Man is the film during the Coens’ turbulent years which began their ‘Pull up! Pull up!’, so that they in fact, like Martin Scorsese, achieved a great Late Period. For the criticisms above overlook what integrates the film. The rug that really ties the room together is not only suffering, à la The Book of Job, but uncertainty about what, or whether, it means.

Larry’s story isn’t quite one of ‘a series of misfortunes’. If they were mis-fortune, that is, bad luck, he wouldn’t agonise about them so. The reason he does is because of the possibility that everything that’s befalling him has a meaning. Like Job before him he wants to know ‘What did I do?’

This soul-searching in the film comes from a physics professor, i.e. someone at the purest, most materialist end of thinking. His sufferings though lead him to the other end, to those masters of metaphysical speculation, rabbis. Three of them, to go with Job’s own three rationalising friends.

Like them, the rabbis are “miserable comforters”. The first, Rabbi Ginsler, fails to solace with bromides about finding wonder even in parking lots. The windbaggy second, Rabbi Nachtner, tells the inconclusive story about the teeth. And the third, Rabbi Marshak, Larry tries to but never gets to meet, Kafka-style: he only gets the silence of God. Faith has no final answers either, no certainties.

The story of Arthur, Larry’s brother, reiterates this fence-sitting. He’s a gambler who’s formulated something called the ‘mentaculus’, which we see as a journal of closely-printed code and crazy diagrams:

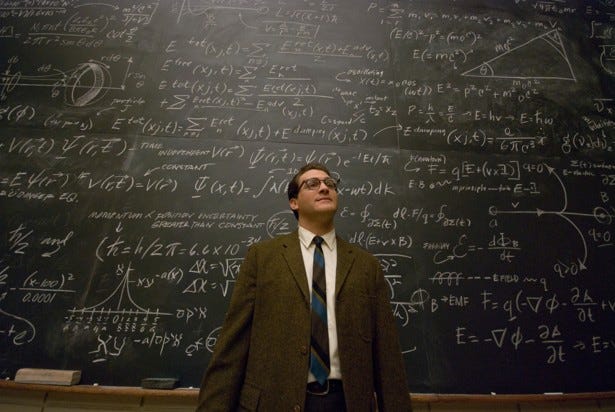

This image rhymes with that of the vast maths on Larry’s lecture-hall chalkboard:

Arthur plans to use the mentaculus to beat the odds at cards - “It really works!” Danny tells his dad - meaning Arthur’s found a way to defog uncertainty into certainty, like Larry’s physics tries to. Although, as Larry warns (himself) in a dream, even physics has dead-ended in the Uncertainty Principle:

The mentaculus obeys this principle, which is also a formal one of the film. We never find out whether its mathematics would’ve allowed Arthur to find the ultimate order behind seeming chaos. First he’s arrested for illegal gambling then pursued on charges of solicitation and sodomy. Sat in despair at a motel pool Arthur curses Hashem - the Jewish euphemism for God, literally ‘The Name’2 - for giving him nothing while his brother Larry has so much, like his (for now) better health, his (tenuous) job, his (soon-to-be-broken) family…

Of Larry’s family, his son is the one with the most screen-time, but his and his father’s stories don’t clash. But that doesn’t mean they don’t meet; they just do so in counterpoint, to emphasise the film’s core question: is there a moral order to the universe, in which suffering has its role, or is all suffering meaningless?3

On the one hand, Larry is suffering in consequence of not being moral or Serious enough (or even because, as some have read it, he descends from the married couple who fatefully crossed a dybbuk). This stance explains why the film pairs Larry with Sy. Larry bests his rival by default when Sy’s killed in a car wreck; later we learn Sy was writing poison-pen letters to Larry’s tenure committee. He was a backbiter, a hypocrite, a coveter of another man’s wife and got punished accordingly by dying in an ‘accident’. Such a stance would make sense as well of Larry and Danny’s fates. Danny smoked too much of someone else’s weed and got stoned during his Bar Mitzvah. While he escaped secular punishment by out-running his weed-dealing classmate, he can’t outrun the wind; a tornado looms over his school in the end. At the same time, the moment that Larry changes a student’s grade to avoid more hassle with his tenure - the academia version of bearing false witness - he gets a call from his doctor with (implied) bad news. Yes, there is a coherent moral system to the universe.

But the way the Coens intercut the ending implies the father has fated the son: we go from Larry’s ethical failure to the Danny’s confrontation by the tornado (the film’s version of the whirlwind from The Book of Job, that famous windy non-sequitur in which God essentially asks an aggrieved Job, ‘Do you know who I am?’). Why should it be the relatively less sinful son, not to mention his classmates, who’ll suffer worse? Or do they suffer only in relevance to Larry’s trials, as with Job? But surely neither father nor son’s sins are in proportion with their lethal consequences? All the characters in the film who protest “I didn’t do anything” can be read then as a legit protest against unjustified suffering. The fate of the schoolchildren makes any moral system whereby Sy was punished for wickedness incoherent. That the film ends on Danny and not Larry is the Coen brothers’ final statement on that unsettling contradiction.

They won’t resolve it because of the film’s second unifying principle: uncertainty. This is what motivates the subplot with Larry’s student Clive. Its payload is when he confuses Larry by saying “mesa misa.” What he means, in his Korean accent, is that Larry’s accusations of bribery are “Mere surmise, sir.” A re-statement of the film’s agnosticism about meaning: any certainties we try draw from suffering are mere surmise, sir.

A restatement or replay as well of the film’s opening chord. The Yiddish prologue concludes with the old man staggering from the married couple’s home. Either he’s shrugged off being stabbed by the wife since he is, as she thinks, a dybbuk, or he’s about to die, being merely a man who’d accepted shelter from the husband. Neither of them knows for certain: the dybbuk/man walks out into blank snow.

But “even though you can never figure anything out,” as Larry says in the clip above, “you will be responsible for it in the mid-terms.” Ignorance of The Law is no excuse. When a subscription service calls Larry asking him to pay for a record by Abraxas, he denies he ordered it, instead accusing Danny. But the caller insists he “asked for it.” As we learnt in a previous post ‘Abraxas’ is a word for God in gnosticism (a linguistic, if not semantic, counterpoint to agnosticism) while ‘asking for it’ is another way of saying Larry is responsible. This might be the same point of Rabbi Nachtner’s supposed shaggy-dog story. As worked out by intrepid Redditors the Hebrew on the goy’s teeth was misread by the rabbi as ‘Save me’. It should actually read ‘Convict me’. By this view, all the characters in the film who protest, “I didn’t do anything” can be read as them bucking against their just, albeit inscrutable, desserts.

In such a confounding universe, what can anyone do? We get a hint from Clive’s father. He threatens to sue Larry either for defaming his son with accusations of bribery over a grade, or for not following through in changing the grade despite having received his son’s bribe. When Larry is left exasperated by the contradiction the father (The Father) urges him: “Accept the mystery.”

Another message comes to Larry not directly but to us, via the parallel the Coens make with Danny’s storyline. Danny, in the run up to his Bar Mitzvah spends his time at yeshiva getting stoned and listening to Jefferson Airplane. Yet he’s the only one to get any sort of response from God, in the form of white-bearded Rabbi Marshak, the very same whom his father never managed to access.

Marshak starts by quoting Jefferson Airplane, listened to on Danny’s confiscated earphones, and ends by saying: “Be a good boy.” This advice chimes, if not answers Larry’s protests that he’s “tried to be a serious man, you know. Tried to do right.” Which itself chimes with Job’s radical jeremiad against God, “Did not I weep for him that was in trouble? was not my soul grieved for the poor?”

Job, though, was incontestably a good boy, a serious man. The sting of his trials was that he’d led a righteous, if comfortable, life before God and The Adversary put him to the test. A fourth friend, Elihu, chastises Job and the three others, telling them that God is both impartial and unaccountable. Suffering can equally befall the Arthurs, Sys and Larrys of the world. But/so you still have to be good. Don’t covet your neighbour’s wife. Don’t change students’ grades even if they bribe and blackmail you. Don’t despair. And when you nonetheless suffer either what Nadezhda Mandelstam called the privilege of ordinary heartbreaks at the least, or at the most disasters of Biblical proportions, don’t torment yourself with why.

This might be the ultimate meaning of A Serious Man: that we add insult to injury by reading meaning into our suffering via our storytelling about it, or rather storymistelling. The Book of Job would have it that only “in a dream, in a vision of the night” does any wisdom come; “Then He openeth the ears of men, and sealeth their instruction”. Or, to reframe and reclaim this in secular terms, in those dream visions in the dark we call films. Because there is no meaning in this world, only in our stories about it.4

“Your faith was strong but you needed proof / You saw her bathing from the roof / Her beauty and the moonlight overthrew you” etc.

Arthur’s story is, I’m guessing, a reference to or spoof of Darren Aronofsky’s film Pi, in which a mathematician discovers a number that can predict the stock market and/or is the unspeakable true name of God.

Nietzsche believed giving meaning to suffering - ‘intension’ - was one of humanity’s greatest self-owns. Animals hurt; but they don’t wonder what it all means and are probably the better for it.

This, in the words of Morrissey, “might sound trite, but it’s true you know.” Just try, though, telling anyone into Critical Theory.