(A version of this article was published at The Talking Book, 2/10/17)

Many have praised the child actors in It - and with good reason; few have praised the film for being especially horrifying. The consensus growing that It is a ‘great modern horror’ seems to be more down to the former than the latter.

Does a horror even have to be scary to be great? The gut reaction is that how scary a film is can’t be the measure of how good it is because what you find scary is not what I find scary (even if we do have a lingering, if confused, sense that a comedy not being funny to us still makes it bad).

Most people jump at sudden noises and sights. And a given film can have better or worse jump-scares, it can trick your expectations to make a jump that bit scarier: the scare coming after the beat you expected it on or from this negative space and not that. But jumping is still instinctual. You didn’t learn from horror films to be scared when something jumps out at you.

Your fears, though, you had to learn from somewhere. If fears are subjective — and they must be, not even pain is universally feared — then no single film can feature what each person in the audience is going to find scary. But even with a niche fear of yours (wigs, cherry stones, toast eaten from the wrong side, at one time clowns) a story you told about it might still manage to scare others. It’d depend not on whether we shared your fears but how well you told the story. So what is it, then, beyond jump-scares and private fears that we’re confronting in a well-told horror film?

How horror horrifies

One kind of horror, usually an older kind, is about what is glimpsed. In part this is to do with the make-up, costumes, and special effects available at the time. But we should be careful about projecting our modern squeamishness about artificial-looking special effects as the sole explanation for the amount of screen-time they once got. It wasn’t only because filmmakers were worried you’d be able to see the Man-in-Suit that horror used to come at you in a flash. It was also the combination of the shock this would give you and the horror of the unknown — of what was behind or around the thing of which you only got a glimpse.

Nonetheless, with newer special effects, filmmakers have been able to risk horrifying you in longer takes, where the point isn’t to jolt you with what you think you saw, but to make you look straight at it. Compare this moment from Alien:

with this moment from the Japanese horror film Kairo (or Pulse):

Pulse didn’t supersede Alien, no more than a new part of a map supersedes another. Neither was its strength its originality (American Werewolf in London and The Thing were great, earlier examples of in-your-face horror). Yet there’s a reason why, in the year 2001, Pulse was scarier than bump-in-the-dark throwbacks like The Others or Alien-esque creature-features like Guillermo Del Toro’s Mimic films. Pulse used an old fear which had found a new form (morbid loneliness via internet-age technology) to show you — and straight on — something you’d not seen before.

In one sense horror is a conservative genre, relying as it does on notions of normality versus abnormality, of the unknown being a threat. A less conservative way to think of horror is that it drags admissions out of our suppressed selves — horror is the exorcist. Look away and go watch if you’ve not seen it, but micro-budget British film The Borderlands (US: Final Prayer) has an ending that isn’t horrific because of its body-horror or monster elements. (The special effects are basic to non-existent.) It’s because the found footage device — that non-editorialised and hence confessional feel— matches how the gruesome predicament at the end is somebody’s horrible mistake. We’re peeking into the worst moment of somebody’s life, and one which was all their fault. What are the mistakes in your life you know there’s no coming back from?

Why a clown, cousin?

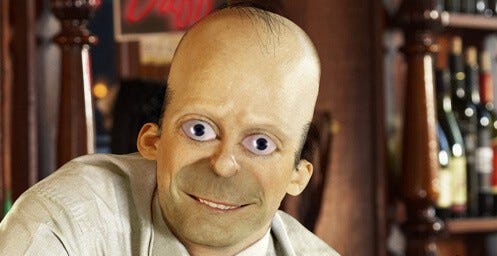

As well as the source novel, It takes a cue from Stephen King’s novella The Body, or more specifically Rob ‘Russia’ Reiner’s adaptation Stand By Me. Like a straightened funhouse mirror, Stand By Me’s love story reflects the horror story of It. Both films feature a kind older brother, although in Stand By Me he’s the one who dies; both feature gangs, including one with a switchblade-toting bully; the good gang includes a kid who’s a natural leader, a kid who makes up stories he tells his friends in the woods, and a fat kid (the former two combined in It as Bill Denbrough, and separated in Stand By Me into Will Wheaton’s bookish Gordie Lachance and River Phoenix’s Chris Chambers). Then there’s the bespectacled motormouth kid who makes Your Mom jokes:

Director Andres Muschietti and screenwriter Gary Dauberman are keen to get this aspect of Stephen King right, the summery nostalgia for intense childhood friendship. (In the book of It, King used the memory spell over the town of Derry to accentuate the melancholy of how big childhood is, yet how much of it you forget.) But the filmmakers neglect another, crucial aspect of the book: the kids’ relationship to adults. Especially that avatar of everything wrong with adults, and the oldest character in the story by far: Pennywise.

The character of Pennywise the Dancing Clown pokes at a particular sore in us. The best scene in the new film shows exactly which. Hypochondriac Eddie Kaspbrak wakes up from a fall to see he’s broken his arm; then he sees a white-gloved hand poking out of a fridge. The fridge opens to reveal a stuffed body, which unravels into Pennywise, who gives the boy a bow before proceeding to torment him. Jack Dylan Grazer’s portrayal of horror here is as great as the glee portrayed by Bill Skarsgård. The clown’s contortionist entrance has the same purpose as when It makes as if to bite Eddie before backing off: to relish how the boy reacts.

Stephen King has said he picked a clown for his monster because he himself finds clowns scary (coulrophobia was boosted but not started by Pennywise). Yet a clown is still a canny choice. Beyond the causal loop that’s since come about—i.e. this clown is scary because clowns are scary — the monster being a clown works so well because Pennywise finds your fear funny (as well as flavourful). Sadism, briefly, is pleasure in others’ suffering. The more troubling detail of sadism, however, is that it’s not just any pleasure: it’s joy in suffering, laughter at suffering. Pennywise’s laughter at Eddie is the self-satisfied kind that adults make when they jump-scare a child.

Outside of the natural world, the thing children have most to be scared of is adults. The unequal power dynamic between adults and children, so lazily and often succumbed to, suggests that the origin of The Monster might not have been the relationship between human prey and animal predator but between infant and adult: that first risk, that formative danger. Which makes baby-faced Bill Skarsgård, for all his game efforts, inherently miscast.

Everyone had been waiting for how the filmmakers would portray Pennywise, especially that part of the audience traumatised by Tim Curry in the TV miniseries. And Skarsgård’s is good, though more for how he sounds than how he looks. His “They all float” comes out like “I am Groot”. (At other points he sounds like Griff Tannon asking “Since when did you become the physical type?”) But the way Skarsgård’s shifts from a clown smile to a raptor stare before getting violent is mainly animalistic (snout extending like a goblin-shark’s out of the humanoid disguise). In Tim Curry’s performance, Pennywise’s laughter would flip from joy to contempt - laughter as a mockery of laughter. What’s lacking in Skarsgård’s performance is this sneer: of the abusive adult. The sort of adult, childlike themselves only in a mercenary way, and with violence and ridiculing contempt just below the surface, that’s best summed up by a clown.

What is It?

A giant spider. But what else?

The obvious association with a child-killing monster is a child-abuser. The film can’t escape that; its images of Missing Child posters, the pathetic mementos of abductees, the adults who look the other way, draw at least some of their aura from their real world equivalents. Is it because of this uncomfortable association that the film is otherwise so eager to defang as much as it can within the confines of the story we know (the only element that can’t be changed being a clown that, you know, eats kids)?

Take Beverly’s abuse by pretty much everyone apart from the Losers’ Club, which still occurs in the film. But what doesn’t — unsurprisingly — is the conclusion to the Losers’ Club first showdown with Pennywise. The gang get lost on their way out of the sewers, so Beverly has sex with each boy, to reorient them figuratively as well as physically. E Alex Jung for Vulture points out that this moment in the novel has aged poorly but also that the film is “simultaneously both more PC and more conservative” (and, I’d add, more prurient). For anyone worried about the gross implications of a young girl deciding to have sex for the utilitarian reason of saving her male friends, be assured there’s none of that in the film: instead, Beverly is a damsel in distress and in a trance; by the end, she’s afloat so not even supporting herself, waiting to be saved by the boys. While the bond that unites the group is now just Bill deciding they should make a blood oath with a shard of glass.

Yet the original writer-director Cary Fukunaga, who left or was asked to leave the production, managed to find one of the myriad ways to resolve the difficulty of this scene from the book, one that avoided being exploitative while maintaining Beverly’s agency and authority:

BEVERLY:

Guys, stop it. Focus.

Everyone turns to Bev. Their muse. Their light.

SHE TAKES EDDIE’S FACE IN HER HANDS

SHE TAKES STAN’S FACE IN HER HANDS

SHE TAKES RICHIE’S FACE IN HER HANDS

SHE TAKES MIKE’S FACE IN HER HANDS

SHE TAKES BEN’S FACE IN HER HANDS

SHE TAKES WILL’S FACE IN HER HANDS

When Stephen King wrote the sex scene he used the familiar euphemism of ‘it’ - as in ‘doing it’. But that doesn’t mean ‘It’ was sex all along. What It is, I’d argue, is the adult in the many shades of the word. Kolleen Carney writing in defence of That Scene describes the sex as adult in the sense of maturity. But becoming an adult is also your graduation into the class of people that gets away with murder. (How cosmically evil the impunity of adults can seem to a child.) We hold adults morally responsible because, by growing up, they’ve gained real opportunity to abuse those with less power, which in the main plot of It means the young, and in its wider world means the poor, the female, the black, and the gay.

The film defangs this too. In the novel, Pennywise is the cause and effect of racist and homophobic violence. In the film, bully Henry Bowers uses the word ‘fag’ but not in any way that differentiates it from ‘normalised’ playground usage. Ben Hanscom makes an off-camera reference to ‘a racist cult’ that burned down the Black Spot nightclub; but he and the film don’t specify the victims or perpetrators — the ‘Maine Legion of White Decency’ that targeted black US servicemen.

Which links to the unremarked traducing of the character of Mike Hanlon, the one black child in the Losers’ Club. The novel’s gentle, budding local historian becomes in the film the cool action hero with a bolt-gun, who, as far as we know, kills a guy and, if the reports on It: Chapter 2 are to be believed, grows up to be a junkie. Downgrading a character in such a way is apparently less remarkable than having a bully be openly racist, or naming a white-supremacist group by name. The racist hatred of Henry Bowers is meant to be his inheritance from his father, because racism is America’s inheritance. Pennywise is an example (a role model) to kids of the founding hatreds of the adult world.

The sad fact is the more you learn about the making of It, the more you suspect the reason they didn’t foreground Derry’s (read: America’s) bigotry has nothing to do with sensitive caution for how even a sympathetic portrayal of minority suffering can normalise it. They just didn’t want the film to be taken as an indictment of the hatreds that run our society in case the current cupbearers of said hatreds took the film as being in culture-war opposition to them and so didn’t go watch it. ‘We don’t mention such things in polite company’ genteelism returns as corporate social responsibility…

Responsible horror, though, is an oxymoron. Only the most delicate prude from a generation back would find the gross-out horror of the new It gross, or even the bad language bad. This is not a question of ‘darkness’ or an X-rating. Look at the miniseries of It, which made (which had to make, by TV standards) Beverly’s abuse by her father more implicit than the leering new film, but whose Pennywise (“Don’t you want it? Don’t you want it?”) returned the subtext so creepily.

We ought to have entertaining horror films, crowd-pleasing horror films. But a tentpole horror? The decisions Fukunaga made in his script evince a sober calculation of what was artistically possible within the constraints of the genre, medium and market he was working in. The decisions of Muschietti and Dauberman seem to be geared towards only that last item. As if their plan was to make a horror film that was only as horrifying as it needed to be to still be classed as a horror but not too horrifying it’d upset anyone. As Fukunaga warned:

“They didn’t want any characters. They wanted archetypes and scares… They wanted me to make a much more inoffensive, conventional script. But I don’t think you can do proper Stephen King and make it inoffensive.”

How to have teeth

The miniseries of It is elegantly structured, in Part 1. The story moves back and forth between 1990 and 1960 (the section of the book called ‘Six Phone Calls’), with older Mike Hanlon’s calls to each member of the Losers’ Club initiating a flashback for them. (To avoid risking money had the film flopped the new It features no expensive Hollywood actors playing the grown-up versions.) This structure warrants the episodic scares we get in flashbacks, which in the new film are just One Thing After The Other. The structure is intelligent too because the device itself changes and adapts: the audience doesn’t have to see every phone call once they get used to the pattern. Each flashback we do see moves the story along in the 1960 timeline. Notably, and ominously, we don’t see Stan’s flashback, but work our way back towards it: his face-to-face encounter with Pennywise in the sewers at the end of Part 1, and, in Part 2, a moment from weeks before, when he was trapped in the house on Neibolt Street with Pennywise-as-mummy. Because the pattern was set to be broken, to show how Stan was different — the unlucky one of the Losers; his flashback gets saved for last to explain his suicide. (Somebody writing ‘It’ on a wall in their own blood after slitting their wrists was the first representation I ever saw of suicide. What could scare a grown-up so much they’d kill themselves?)

In the miniseries and novel, It manifests as children’s pop-cultured fears. In the film, we see phobia- and trauma-flavoured versions: the leper, a dead Georgie Denbrough, and Beverley’s abusive dad. But otherwise, and maybe for fear of Ready Player One-style tackiness, the film only features a mummy during the big fight at the end, and not as a manifestation of a character’s fear but as an Easter egg to service the fans. Instead the filmmakers put all their chips on their iteration of Pennywise the clown.

How do you manage to mess up a scary clown? Pretty easily, it turns out, if you’re not sensitive to your story existing in a post-scary-clown world. (Too Many Clowns!) Acrobatic bunny-toothed new Pennywise is admittedly more manic cartoon than party entertainer. But you wish this had been taken to more of an extreme; after all, few things are more horrific than a ‘real’ cartoon.

Pennywise’s iconic status actually gets in the way of the horror if pandered to. Fukunaga was aware of this fundamental problem: that any new It film would have to function in a world that the novel and miniseries had helped to create:

“The main difference was making Pennywise more than just the clown. After 30 years of villains that could read the emotional minds of characters and scare them, trying to find really sadistic and intelligent ways he scares children; and also the children had real lives prior to being scared. And all that character work takes time.”

Muschietti takes no time in showing us Pennywise, who appears twice within the first 20 minutes, in that standard, modern, front-loaded way — this truly is the Golden Age of Horror. One of these scares, involving a creepy painting, steals a trick from that genre paragon The Conjuring 2 (which did it better). It’s more that Muschietti won’t risk restraint. He goes the opposite way, he won’t risk you missing that Something Scary is about to happen, even if it won’t be scary when it does: the bass rumbles on the soundtrack, children giggle in the distance. His one other trick is the suddenly charging monster, as though the spider in your bathroom doorway suddenly came shooting at you, and as featured in his first film, Mama.

Because of a culture that won’t separate fiction and reality, we mistake what we might find scary in real life with what’s scary in a story. A real house like the one on Neibolt Street might scare especially our fiction-addled minds if we had to go inside it; but the film’s house on Neibolt Street, the way it’s set-dressed, lit and shot, all the CGI: it’s like the cackling of Vincent Price in cinematic form. A haunted house — as with the leper and the mummy — is what the kids in the film find scary. But that’s not enough; the challenge is how to portray something the kids would find scary but that the audience, so familiar with the horror genre, will find scary too.

It’s not that CGI is less worthy than the ‘real’ special effects of older films; it’s that Muschietti’s use of it is unremarkable, trite, in service of cheap shots like halved zombie kids or stabbing crab claws, which remind us of what we know and so can’t be scary unless we’re already scared of such things in real life. Neither is the point that the CGI should’ve been more ‘realistic’. The make-up and claymation of the miniseries were horrific because they looked artificial, in the way that we know hell will have bad special effects.

The tritest moment, however, if not the most dunderheaded bit of onscreen-literalism in recent years, is Muschietti’s interpretation of those famous words, “They all float down here!” (significantly, the much-repeated tagline of the film’s ad campaign). Are these words of Pennywise a reference to corpses facedown in the sewers? Or something even more horrible? What might ‘float’ really mean? Where might ‘down here’ really be?!

No, the corpses actually float — as in, in the air.

You bastard

Muschietti might be an effective director of actors — the kids are all as good as the screen-time each one gets, each capable of portraying fear, humour, affection — but this only makes the rest of the film more of a betrayal. The film’s at its best in lighter-hearted scenes; dialogue like “Derry used to be a beaver town.” / “Still is!” gets a big laugh. But how should we feel about lines like “I want to run towards something, not away from something”, especially when given by Beverly as a reason to stick around to fight a child-eating monster? Bill’s defiant speech in the miniseries, calling Pennywise “you bastard”, counterpointed with his teary pleas to his friends of “help me”, is more moving than any scene in the film; and this has nothing to do with the respective child actors but with poor story choices.

The curse festering in screenwriters’ mind, rearing up every 27 movies: the hero must have a sympathetic goal, an emotional arc, and you have to make the story visual at all times. Hence why Bill can’t just explain to his father how he thinks his brother is alive and which two locations he might be in; he has to set up a hamster-tunnel model with action figures and tap water pouring into labelled trays — as convoluted a way to explain an idea as Doc Brown recreating Hill Valley from cans and boxes (which at least justified itself by ending on a macabre joke). Hence why Bill doesn’t want revenge like he does in the novel but to save a brother he hopes is still alive. His emotional arc is to admit his denial (visually! shooting an apparition of his brother with the bolt-gun) so we can end on a scene of closure, instead of the ironic and dread-tainted victory of the original story.

This kitschy simplification starts the film as it means to go on. In the first scene Bill no longer mixes affection for his little brother with calling him “a shitty a-hole” as he does in the book. He’s only affectionate. When characters reminisce we hear sound effects of their memories like in some hokey radio drama. All the adult characters are broad creeps, even poor Eddie’s mum, whose Munchausen’s-by-proxy is no longer her confused way to protect her child from the dangers she detects through the Pennywise fog in her mind but part of her opioid white trash kookiness. Meanwhile the wilful blindness of the rest of the adults gets double-circled in red. Should we respect the audience to work out for themselves the evil hold Pennywise has on the town? Or should we put a red balloon in the car of the couple who avert their gaze from Henry’s bullying? In the same condescending way the film zooms in and slows down to show you Mike has brought his bolt-gun along for the ending — an ending which is a cliché Hero’s Sacrifice. In the book, Beverly was the hero. True, in the film, she does land the final blow on Pennywise when It transforms into her dad. But notice the difference it makes to a character whether their actions are motivated by ‘emotional arc’ logic or whether they save the day by exercising a superior skill (like being best at slingshot).

Muschietti’s aware he’s making a film in a world where It has so much cultural baggage, just in all the wrong ways. He shoots the opening scene with lingering, tender shots of Georgie’s paper-boat under construction, the kind of museum solemnity not warranted by the moment itself but directed at the savvy audience. In the discarded version of the script, the murder of Georgie that follows is intercut with shots of a cat on a porch eating its own food. In the final film, the cat, now foodless, is still there watching — but why? Because of Alien? Because people like cats?

It goes without saying that cheap talk of Fukunaga’s superior version is fantasy; his finished film might also have been a let-down. But at least he was applying himself thoroughly to how, in 2017, you can even make a film of It. Had the film we ended up with not been based on a book we know it would’ve been taken for what it is: funny, with good performances, but essentially a horror for people who don’t like horror. In other words, Muschietti’s It is to horror what clowns are to comedy.

Too late!

It is halfway to making a billion dollars and so an all-star, Ocean’s 11-style cast is being assembled for the sequel: Jessica Chastain from Mama is in talks (not Amy Adams?) and, who knows, maybe Lakeith Stanfield will play Mike, and Seth Green will reprise his miniseries role as ‘Beep beep’ Richie. This is how commercial success and the collaboration of critics establish a new standard for what is acceptable and so possible in a horror film. Why should any horror try to be better than It? Didn’t you see how much money it made?

But a popular horror doesn’t have to be a safely-buckled rollercoaster ride of wisecracks and jumps. Nor a conservative warning against the unknown, nor a thoughtless regurgitation of society’s ugliness. Well, we don’t need reminding of monsters, we have the news, so the complaint goes. We have our lives.

Cruelty, abuse, violence are immanent in the world: always just below the streets. (Not for nothing does Derry fall when Pennywise dies.) But making horror more horrific doesn’t just have to mean maximising the genre’s sadism — your horror for their profit. The way to make a horror truly more horrific is to think, with as much pity as intelligence, about what scares us and why. With that sort of thinking an It film would be like the graffiti on the Derry Memorial in King’s novel Dreamcatcher — “Pennywise Lives!” — but no longer as the monster’s defiance. The Losers’ Club are victims who grow up to be victors. Yes, Pennywise lives all right. So what are we going to do about it?