Low-browse literature

You will crawl on your belly and you will eat dust all the days of your life

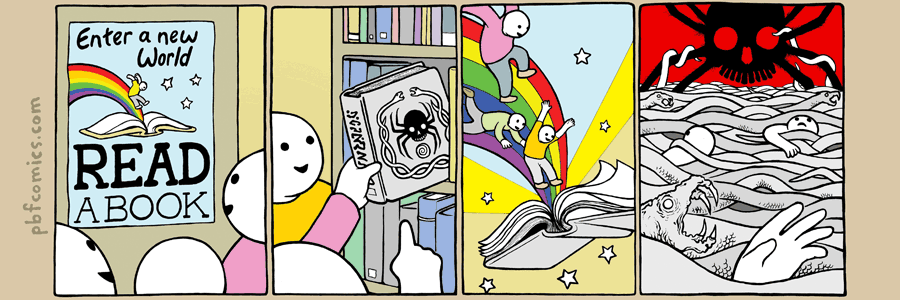

When I was a kid, a bookshop was like an abstract painting of a toyshop. The attractive colours and imagery were still there but with other dimensions and elements encoded or placed at a point of remove. The cover art on kids’ books hovered somewhere between the technicolour luridness of rental video cases and the staged tableaux of board-game boxes (where everyone is smiling but no one is looking at each other). More than the various pictured gangs of kids, what stood out were the silly, surreal or grotesque: a badger in plate armour, a three-headed witch on a motorbike. Yet the artwork was never meant to be representational - what you saw wasn’t what you got - so much as evocative.

This evocativeness continued through childhood, complicated with my growing awareness of authors as well as their books. Although the local bookshop had too strong a whiff of worthiness and school to ever feel like any Hall of Fame or pantheon, there remained anyway a museum grandeur to the shelves. (It probably helped I was still ⅔ the height of a bookcase at that point.) The range of books, the density of their content, the emblazoned author names embodied what seemed back then like the infinity of adult life. And if your own name was up there?…

Arrived in actual, finite adulthood, and what’s worse, with dreams of being a writer, I stopped finding bookshops grand. Aged 19, I’d swagger around the megastores, picking up this or that hot new release to raise an eyebrow at, sure that I could do better, that so much of this stuff literally wasn’t worth the paper it was printed on. Granted, a certain amount of arrogance can help give a young artist their first push: the hot air needed to get the balloon afloat. But what 19-year-old me didn’t appreciate was that his writing was worth as little, and that’s why it hadn’t been published. Instead I roamed bookshops picking at my narcissistic resentment. No, these weren’t books; they were personalised fuck-yous.

Maturity is self-preservation. You grow to learn there are few more foolish habits than hate-browsing. All spite is self-spite in the end. Writerly dreams notwithstanding, you stop seeing bookshops as a cross between a rival highschool’s trophy cabinet and an album of someone else’s party snaps. You come back to where you started but a little refined: a bookshop as the original old curiosity shop. Junk and gems. The flow of hot new releases over the cold stones of the classics.

It was with this kind of serenity I recently wandered into a train station’s WH Smith (or ‘The Bookshop by WH Smith’, like it’s doing an impression). I was mostly prepped for the journey: camping rucksack on my back, cardboard flagon of tea bought and waiting inside a paper-handled takeaway bag, music on my headphones at the start of a sufficiently long playlist. I could’ve done with something extra to read - what new possibilities might this bookshop hold? - but otherwise was happy to just be walking the aisles, when I heard someone yell.

Rubbernecking, eavesdropping, curtain-twitching—a modern addition to that list is unheadphoning: taking out one earbud with the casualness of scratching your face when in fact you’re taking a lofty peek at what all the commotion is about. Manoeuvring my rucksack and the paper bag with the tea so as to not disturb any displays, I edged around a pillar to get a better look. The person yelling was the woman behind the counter. The person she was yelling at was me while pointing to the laminate floor.

In the climax of Carrie Amy Irving notices a pitter-patter of blood then follows it back with her eyes to the horrible source. I looked down. Along the floor was a winding stream of dark liquid that led to my feet. More exactly, to the paper bag I was carrying at my side. In which the large tea had fallen over and been leaking from the lid, till the bag couldn’t take the soggying any more and had given away at one corner. Like a can of paint punctured then hung from the back of a car to mark where it goes, a line of tea traced my route around the bookshop, pooled into puddles wherever I’d paused to pivot a new book off a shelf and have a clever thought or give a known book the equivalent of a chuck on the chin, all the while listening to, I dunno, Philip Glass.

Apologising, apologising, I easily righted the now empty cup in the bag. From behind her gun-turret of a counter the woman stared at me, as if no one knew the things she’d seen, and now this guy had come sashaying hot tea over her shop floor like a fat tail with which he’d been knocking over tables and shelves. I rushed upstream and from the shop in search of a bin with the sodden bag held out and cradled underneath, like it might blow any moment.

At the next moment, I could’ve left the tea-spill disaster behind me. I had an escape route plus a getaway car: my train was at platform. With a David Cameron doo-bee-doo I could saunter off.

The laminate floor, tea puddles the same colour, throngs of distracted commuters… I went back and asked the woman whether she had any tissues. She said no, with implied of course not, you wank. I said maybe someone else might, looking around. Other customers were turned Blair Witch Project fast to their respective corners. Cafés around the station would have tissues, I said. Any residual customer-facing patience burnt off, she said she was the only one in today and couldn’t exactly leave the shop unmanned to find something to clean up my mess.

I’d go get some then, I said. But Delice de France had too long a queue. Pain Quotidien felt too on the nose. Caffè Ritazza however was only next door. One of its baristas grabbed me out white tissues from the steel dispenser right there, till-side. I hesitated over my handful then said there’d been a spill. He wound out a muff of blue kitchen roll to give me. I said I needed more. He asked, “Where is this spill?” “Next door,” I said. He said, “Then it’s not really our problem.”

Half-empty-handed, I rushed back to the problem. First squatting, eventually on all fours, I retraced my milk-and-no-sugar slug-trail. (All throughout I kept the snail shell of my rucksack on my back.) In two or three mops the blue kitchen roll was oozing. Soon I was pushing tea side-to-side like a windscreen wiper. My hands were like those mop-brooms they use on drenched ship decks. Things fell apart, meaning the kitchen roll. I resorted to laying down a crazy-paving of white tissues.

Most of the customers ignored me politely. Others didn’t care to pay attention. One woman bent concave away from my mopping as she’d do from a muddy dog. The woman behind the counter had reverted to conscientious bookseller, chatting breezily about the latest Sally Rooney as if there wasn’t a man crawling around to her side.

Down there, I’d come level with the bottommost shelves, not even proper ones, their books stacked not spine-out but face-up, in flagrant disregard of alphabetical order: the about-to-be-remaindered, the undesired. From the bottom shelves upwards the monoliths of the rest of the bookcases loomed over me with renewed judgement.

When it was almost over, just as I was gathering up the last of the white tissue crazy-paving, another batch of customers came in. To them I had no visible reason to be crouched on the floor, pawing here and there. And among them lurked a kid who was far from ignoring me.

Forget evocativeness or resentment or serenity—his bookshop memories would forever be tarnished by the sight of a man on all fours, big rucksack shimmying on his back like an elephant’s howdah: if seeming to browse the bookshop only in the sense of graze. There might be no short cut to artistic recognition. But it’s as easy as a large tea falling over to go from rubbernecker to the rubbernecked.

In more dignified news I wrote about the Hulu show Ramy for Tribune in anticipation of its third series getting a UK release. For those who don't know it’s a “TV comedy about Muslims that’s smart, frank and not cramped either by bad caricatures or good taste.” Watch it! Read it!