You think you’re - maybe not settling down. Settling anyway. A chat with the shopkeeper downstairs lasts for whole minutes now, though both of you are past the point where you could’ve swapped names. The guys at the Chicken Cottage who call you boss you’ve taken to calling it back. So you don’t have roots. But you have your routes. One for cycling, painstakingly plotted to avoid traffic and a violent death on the way to work. A bus route home so rutted in your muscle memory that even at 1am when you’re absent from your head you still manage to keep on track. The only change is when your agency calls.

The new temp job’s near one of the many stations you’ve been through but never to. And, for somewhere between a week and a year, that’s your life: the tail-end of a Tube line, a top deck bus ride past a mysterious park, your short-cut walk through the well-intentioned but crazily circuitous Google Maps route. You wake up masochistically early to work before work then don’t get much done than yawning and staring. Lunch hours you spend writing in a caff, afternoons hiding drafts inside spreadsheet cells.

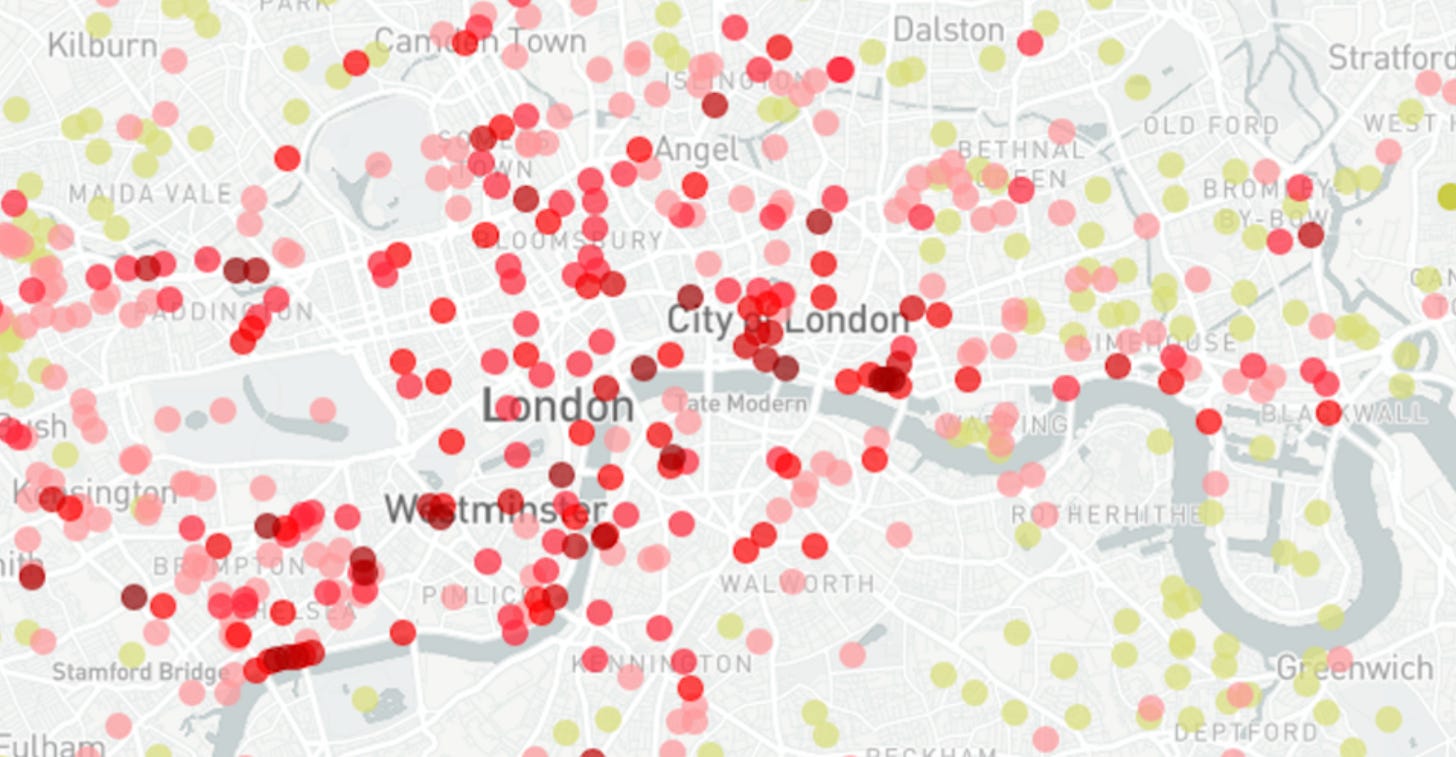

Then a ‘permanent’ job hauls you to a different letter code of the city, though never to the W where all the rejections come from. Or you learn your landlord’s sold the flat for condos and get your two-week marching orders. You break up with someone, they break up with you. The routes you’d worn into the city, back and forth, up and down, fade and drift like the see-through squiggles on your eyes.

Maybe life once had milestones. Your stop-and-start life’s measured only by where you sleep and where you work. Or worse. “The place you’re moving out of,” a friend gravely explains, “is where you’d jack-off routinely without controversy; while the place you’re gonna move in to, it would’ve been outrageous to have previously jacked-off there. And in one day that reverses forever!”

You stay in five places in as many years. Each time you’re surprised to have found yet another pocket of the city. You start thinking London is, not mystically, not literally, but functionally endless. Sure, you could walk all its roads, but they wouldn’t stay put in your head, any more than you can keep counting forever without losing your place.

Each new place comes with a fresh set of routes. All those single-digit years ago, buses didn’t tell you the place-names on an electric ticker; you’d have to rely on a certain row of shops swinging past to flag your stop for you. From night buses to the night Tube, from Addison Lee on speed dial to car-hire apps. Being driven through London a potent weaving of the novel and nostalgic. Names of roads like magic words: open memory. That move-in day when, arms full of books, you tiptoed back just in time to miss splashing vomit. (A wipe of the chin and “Welcome to Limehouse!”) The flat-share where the washing machine stank the whole floor out with the smell of bad eggs, like some thermodynamics of dirt, like each act of cleaning has to be recompensed with an act of soiling. The house party where a rat fell three floors and between your drinks. The entropy of these places, the stand-off between you and the landlord: ignore the sofa arm that’s fallen off? Or fix it again yourself and feel like a sucker? But that steel balcony, too, where you waited topless in the sun for breakfast to the screeching rumble of an endless freight train. The attic far out enough you could look down on the breadth of London and see it was a sink. The terrace that faced on to a road of hourly screaming ambulances, the pavement scattered with broken glass AKA ‘Southwark gravel’—but backed on to a jungle corridor of ten-foot nettles, Scots pine and parakeets. The coincidence of a favourite song coming on the laptop the very same moment a silver ballon like a manta ray floated through your housing estate.

Recurring dreams about moving house. Sometimes the dreamed new place won’t stop extrapolating: more doors than there should be, stairs up to another derelict floor, or down to basement level after basement level, all in a deep blue carpet for some creepy reason. Or the dream place is laughably noisy and cramped, walls made out of balsa wood, single-glazed windows above a violent bus station. You daydream, too: picking out places as you walk the streets. Fantastical place-names like ‘Golden Lane’, ‘Saffron Hill’. The location or accommodation not mattering so much as the excitement each potential place embodied—for you, neither canal-side yuppiedromes nor Bayswater mansions but that yellow-brick square tower you saw, ground and first floors seemingly uninhabited, a high-walled outer staircase leading to a conservatory top with a 360 view. What work you’d accomplish there! (At least a richer form of staring.) Or that terraced relic in Rotherhithe, lone survivor of a Thames-path slum, whose neighbours being long demolished had left it thin, tall and grand, the one book on a shelf. But any new Tube station’s really just a hole in the ground for raising rents. All you can do is daydream about your landlord in a fit of deathbed generosity leaving you the flat, and how you’d make it over, how you’d stay there and stop, lay roots.

You don’t and you won’t. The tender anguish each place gives when you’re moving out and you’ve emptied it. Once a home, now a house, naked as the day you moved in. Each new place a fresh start, so you tell yourself. You can feel it again, the urge to create, to not waste a moment, kicking inside, just in time to get to work and have it stamped out of you. As if shifting the physical coordinates of a mental bomb-site ever helped anyone! As if slumps can be fixed by just moving them slightly! Entire boroughs by now stained blue with how you felt at the time. Break-up pubs you can’t go in any more. And yet heading back from your hometown by train on a cold wet night you still think, it’s OK, London will eat me, endless London. Look how relieved you were whenever you got back to your place, your room at least, to your bed, smaller, closer, a dot against the world. For us, home is the place you don’t want to go back to. But the new places, were they ever homes either? You start to suspect you’ve never lived in London but on it.

Feeling the same, half the people you know up and leave. They’ll write about why. (An Oscars-style In Memoriam montage but for people who’ve moved out of London.) The ones left behind indulge in self-congratulatory fantasies of London leaving everyone else, seceding from the icky rest of the country, as if the city weren’t the sink and source of everything that’s not right with England.

But then you wander into a place as arresting as any in the world you’ve been to: a forest with hundreds of thousands of trees growing amid hundreds of thousands of graves — a cemetery out of London’s ‘magnificent seven’, where it looks like there’s a truce for now between city and countryside, past and future, between leaving your mark and eroding away, nostalgia and oblivion. For a sunny afternoon, you’re settled in that truce.