A Supposedly Fun Film I’ll Never Watch Again

Jurassic World — amusement park of the future, where nothing can possiblie go wrong!

(This piece was originally published at Little Atoms, June 26th 2015)

The only interesting thing about Jurassic World is its relationship to its audience — interesting, and damning, for the film and the audience. The film is so self-conscious and at the same time so happy to admit its cynicism; but it makes sure it does so in a way that tries to implicate you: yeah OK, I am a dumb kid. But then who raised me?

The difference between efficient and lazy storytelling is small. Most films, arguably the better ones, have plot holes, dispense from full logical coherency, as a sort of example of, or testament to, how stories are unreal by definition. This can give us a tricky but positive feedback loop: short-cuts and leaps of logic result, ideally, in a story whose emotional impact retroactively justifies them. Wait, how did she get up there? Was it possible to do that? The story works well enough that these questions no longer matter or, better, we don’t even notice. Your sensitivity then to a story’s logic might be less a sign that you’re smarter than the film, than proof of a kind of deficiency. To suspend even your disbelief still takes a bit of strength. And to be able to do so is not to be credulous, but to know how to read a story (in the strong sense of ‘read’).

But the evil twin to this mechanism is when a story rushes you between loosely knitted-together set-pieces — usually action sequences — that are so isolated and episodic, and peopled with such crash-test dummies, that they expose the short-cuts as coming instead from a cynical, even contemptuous kind of laziness. For example, Jurassic World’s telecoms work when they’re meant to, don’t work when they’re not, and with no more reason than that. This kind of thing is what usually gets called ‘an insult to our intelligence’.

This is an important cliché, which will keep coming up — because the insults don’t stop there. When a rogue new dinosaur goes on the loose, the In-Gen corporation, which happens to have ex-soldiers on tap rather than the usual tragically-bored security guards, decides to tool up and hunt it down; In-Gen, you see, has already sunk costs into researching the military application of dinosaurs. It’d be good here to cut in supporting shots of weaponised cobras and lions being set on enemy forces only to yawn and dawdle off into the underbrush.

So that the audience won’t suspect the film of anti-militarism, its hero is ex-military: The Good Soldier Pratt, with his original glass-bottle Coke, and vintage motorbike, and dude expressions running the whole gamut from frown to smirk. All this focus group feedback-form in an oily shirt manages to do, with his fighting and flirting, is highlight the insult of/to his female co-lead: a character treated with such contempt that we may as well call her Not-Jessica-Chastain.

As the park operations manager, she reveals the top secret new Indominus rex to her potential corporate sponsors not in a private meeting but during a walk-and-talk — because this is what filmmakers call ‘more visually interesting’ — right through a crowd of staff and tourists. (The monster being revealed as sponsored by Verizon isn’t the last of the film’s odd associations with a certain author).

The park operations manager has two nephews. Not her own kids. This is crucial. One is a sort of Not-Joseph-Gordon-Levitt, his main character trait a kind of dead-eyed horniness, always giving girls the scan, presumably to connect with the important demographic of busy-handed teens. His brother, by clever contrast, is a nerdy moppet, maybe a child prodigy, who by the way also believes in ghosts. Negligently babysat by their aunt’s English PA, the boys sneak off on a gyroscope ride, which the older one takes off-road through a torn paddock fence, the plausibility equivalent of jumping into a tiger cage, i.e. for drunks or religious people trying to test God’s patience.

We’ve come a long way when even a David Koepp script seems by comparison a Shangri La. It takes all of four screenwriters to make sure we reach the end of the film with brothers learning to be brothers, their aunt getting her groove back, and Chris Pratt nodding goodbye to his raptor-bro on the misty tarmac, presumably in lieu of a jaw-chook and We’ll Always have Isla Nublar.

Jurassic World reminds you, as we’ve learnt from a decade of boring-ass Marvel films, that the modern blockbuster has worked out it needs only two modes of dialogue. First, the expository, where characters just come out and say their motivations and goals, or describe scenes we’ve watched or are watching, like close captions for the seeing blind, to the point that you want to cry up at the screen, ‘What are you, the narrator?’. Second, the wisecrack. No characterful, non-wisecrack dialogue can exist. Any non-wise-crack dialogue could come from the mouth of any character. The only exception to these modes is the odd bit of Dramatic Portentous, those lines that get immortalised as mottoes under message-board avatars. (Chris Pratt, having warned a newbie he rescued from getting eaten to ‘never turn your back on the cage’, immediately walks off with his back to the cage. With a dry cool wit like that, he could be an action hero.)

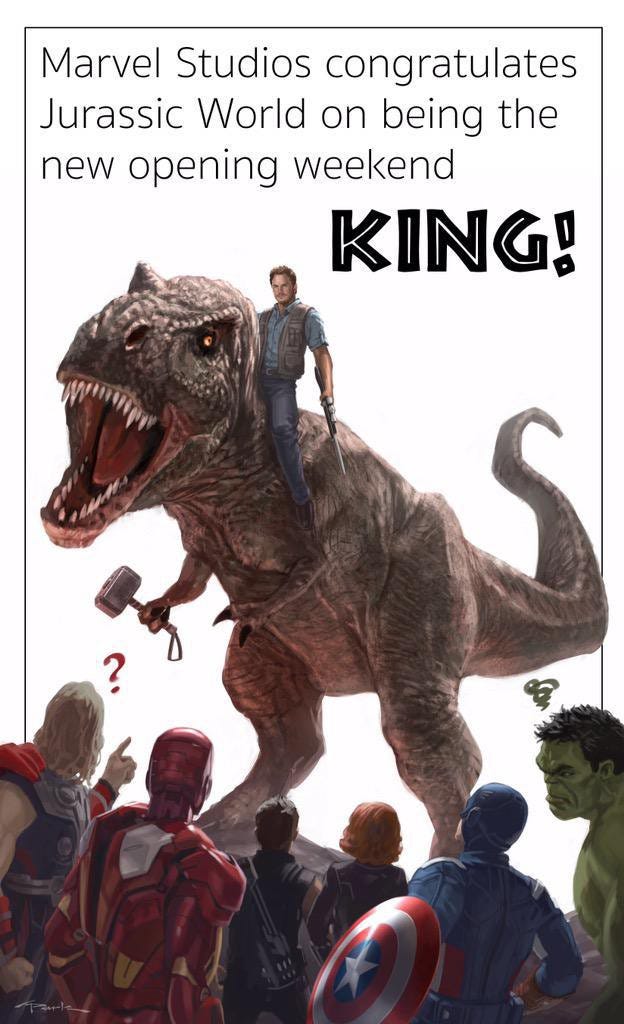

In fact I was so reminded of Marvel films I hung around at the end of the film in hope of one of those cutesy post-credits scenes: at last they reveal the identity of the new Spiderman: a dilophosaurus! (Goo-spitting, web-flinging, same difference.) Jurassic World after all hews to the Marvel formula. That blockbuster dialogue has boiled down to these modes is unsurprising; a film as tour-guide to itself, pointing out everything you need to notice, but lightening up the dry stuff with zingy asides, mascots faux-bickering as they pass each other to make the parents laugh and tip. Unsurprising, then, to see Marvel suck up to its new rival.

Halfway through the film’s ninth threat-less action sequence, my eyes drifted to the background, to the self-referential product placement, to the tourist who runs from the pteranodons while clutching onto his cocktails. I started daydreaming that caught up in the panic then stuck looking after the young brothers would be not Sam Neill but an exasperated David Foster Wallace, sent on his latest gruelling trip by Harpers Magazine to bring back another 20,000-worder.

Because as he showed, there’s mileage in stories about megabuck entertainment and luxury, where the peppy surface masks a huge network of production and consumption, of corporate PR and corporate malfeasance. Take the brutal Crichton film Westworld for starters. Under the weak gloss of Jurassic World, you catch hints of another kind of film: moments where the self-consciousness eases up a little, into self-awareness - playful! fun! - like when the Villain’s monologue about the natural order is interrupted by a dino-attack, or when the control-room Beta Male leans towards a colleague for his hero kiss only to get snappily told ‘I-have-a-boyfriend’. Moments of tension, too, between wonder and its commodification, the workers of a theme park of actual real life dinosaurs droning, ‘Enjoy your ride.’ (Although the bored teen drone is its own ‘Would you like fries with that?’ cliché, i.e. cynicism at its most palatable.) This is the full tally of the movie’s charm.

To bring out these tensions and satirise our theme-park culture would take a filmmaker like Paul Verhoeven, say. (In the Jurassic World he imagines, corporate bigwigs combine Coupon Day with controlled accidents involving the poor, creating a surge in VIP visits; and loud ads interrupt the film with an OTT family screaming down log-flumes and leaping in glee from shock-proof cages, as all the while the stupid dumb downtrodden animals look on psychotically.) Instead, the film Jurassic World reminded me of most was Super 8, dull and shallow in the same way as the Abrams film, with the constant Spielberg referencing: sometimes a cute homage, more often a revealing tic. Jurassic World is full of these surface similarities — an Indy-roll, an attacked woman thrashing in and out of water, a truck chase seen through wing-mirrors, gas canisters flung at the jaws of predators, even an Empire of the Sun hangar reunion. But then here’s me jabbing my hand up to prove I’ve spotted all the references. De te fabula narratur! Because if the film knows one thing, and it’s probably only one thing, then it is its audience.

What makes all these things lazy is what they’re in service of: not even good entertainment, but a mixture of pandering and tutting. If style in art is a way of looking at the world, then a film’s aesthetic choices are part of its moral outlook. Just look at what the film does with its women.

But it’s not enough to talk about the treatment of the female lead as typically disgraceful, as expected Hollywood sexism. Yes she is a character whose Hero Moment is to run in high heels. Yes her arc goes from pitifully childless career-woman to protective lioness. Focussing on this distracts from the deeper problem.

In the original film’s Dr Grant storyline, dinosaurs had to eat a bunch of people for him to realise that starting a family with his partner might not be so bad. This wasn’t particularly subversive or a challenge to gender, but the new film takes a step backwards from even that: instead of a man being invited into a matriarchal order (“Women inherit the Earth”), a woman is taken from a bigshot career, which made her heartless and thoughtless, into real womanhood: i.e. motherhood. As her sister warned her: “You won’t understand till you have kids.” But more importantly, and in a telling post-modern twist, she also thereby earns the right to confer manhood on others. When realising how to save her nephews, she calls out via CCTV (i.e. through a screen) at the Beta Male audience stand-in (sitting spectacled in his computer control-room) with that spanking cry of the age: “Man up!”

(It’s as if men want women to ‘be women’ so they can then be told how to be men, all the while disavowing that this is what they’re up to, disavowing what such outsourcing actually proves. Then there’s the rage and the shame. Depressing isn’t it!)

Somehow even worse is the character of Zara, the English PA, who’s killed off for not letting her fiancé have a bachelor party. In being so, she isn’t just fulfilling the standard sacrificial role of the Too Pretty. She dies to appease the misogyny otherwise directed at the female lead. They are both uptight career-women, share a taste in stylish corporate jackets, don’t pay attention to kids, have similar angular cheeks holding up their continually used phones.

Zara is her boss’s stand-in, her Whipping Girl; she is in the film so that her boss can die, and gruesomely, in spirit, without having to die for real in a way that’d risk the audience admitting to the impulse being roused in them.

Tutting is itself a kind of pandering, to these sort of impulses, and the stereotypes behind them. (At one point, Not-Jessica-Chastain says, “It’s OK to lie if people are scared!” — summing up the M.O. of our pop culture right there.) The film, for example, with its eye on a global audience, seems to be multicultural; but - with an eye on its base - is in fact thoroughly racialised. The unfortunately-abbreviated Pachycephalorsaurses might raise eyebrows only in UK cinemas, but the rest of the film isn’t so lucky, with its Indian billionaire who preaches Vedic humility before nature, the black guy assistant who mediates between his white bosses and the park’s animals; and that’s not even mentioning yet the crafty Chinee.

(It’s worse even than that. Trying to calm down the brothers after a horrific jungle chase, Wallace asks the Moppet, with whom he thinks he might have a precocious-kid affinity, about those strange details in the film he’s sure wasn’t just him: the helicopter crew that served in Afghanistan; the Villain thinking out loud about what the US Army could’ve done with dinosaurs in Tora Bora; the central set-piece of tensed Americans watching on night-vision-green screens as a crack squad hunt down a monster of their own creation… The Moppet looks embarrassed; he’s too young to remember. (Neither did it help that Wallace kept saying ‘OBL’, to the point it started to sound to the kids like a Biblical exhortation.))

It’s not good enough to say blockbusters are stupid. They don’t have to be, and often they’re very smart. Hence there is a reason behind the stupidity of Jurassic World; it’s stupid often enough that it feels like a feature. When we say a film ‘insulted our intelligence’, we also have to ask why it would do such a thing. Well, Jurassic World’s engineers combined the DNA of the world’s most evil animals to create the most evil creature of them all. It turns out it’s man.

The audience’s guilt is emphasised by the audience stand-in character not being the Action Hero but the Beta Male, with his original Jurassic Park t-shirt, and his waxing nostalgic about better times when the dino-entertainment didn’t feel so cynical. (Notably, the man still works there…) This isn’t merely the film’s sly attempt at co-opting, acknowledging and neutralising criticism of itself. It also puts the man-child in the picture. The audience projects their discomfort onto this man, whose nostalgia is given permission, and is indulged to the point of exploited. At one point, and for some reason, Not-JGL and the Moppet stumble across the ruins of the original park visitor centre in an absurd Childhood’s Attic sort of sequence. The teens light a torch with some convenient matches off the younger boy (Why did he keep any on him, the budding firestarter?) and they proceed to stalk the set and stroke the props like they’re looking at cave paintings — So! This is what the 90’s looked like!

But also, and crucially, the audience stand-in is the comic relief. He is mocked, in a light way, thus reaffirming the status of the man-child in the food-chain. This was made just for you. Lol, you dork.

The dual meta-commentary runs throughout - the film apologising for and revelling in its trashing of the original, that trashing literalised: a model of a mosquito fossilised in amber is smashed to pieces; the hill where the Park’s first visitors gawped at a brachiosaurus in that famous first reveal, is now the bloody resting place of a whole herd sport-killed by the I-rex. (More interesting than the usual smug comparison of traditional animatronics versus modern CGI is that this one animatronic shot is the most hilarious. As we close-up on Chris Pratt stroking the rubbery brow of a murdered brachiosaurus, I half-expected it to whisper, in Falcor-like baritone, ‘Avenge me. AVENGE ME.’). But isn’t this massacre of a movie what you all wanted?

There is, though, a flaw in the meta-commentary: does the audience really just ‘want more teeth’? Then why isn’t Jurassic World more in the tradition of accusatory films like Running Man, Funny Games, or even Scream 2? We might just want better films… The accusation is starting to become incoherent. It’s as though McDonalds was arguing they had no part in training us to respond to high-salt and sugar diets. Blockbusters in the Jurassic World-mould are too big to fail, they must make good on their money, so the main heft of the spending is in ensuring a kind of mercantilist market saturation that regardless of quality of or demand for the product will still lead to obedient queues (this reviewer included).

For the film is too slapdash to be making any point about consumer demand or sequels or its audience or much else. But a point remains: that it’s not despite but because of its cheap moves, its story clichés, its character ciphers, its grubby ideology, its careless conman’s shrug and the alternately shameless and ashamed nostalgia — that the film has been such a roaring success.

The pandering is at its worst when the film admits that look, it gets it, it’s not as good as your beloved original. In the Chekhov’s Dinosaur climax, as if the film wants to make a big fake show of how it’s punishing itself for being inferior, the market-engineered monster is beat down by the stars of the original, a velociraptor and T-rex. Despite the congenital bad faith on both sides of the screen, the audience bursts into applause.

If this success isn’t proof Jurassic World was only giving us what we wanted, what else does it show? That the film gave us what we deep down knew we had only been taught to want, despite our claims to want better, and yet still there we were.

A Supposedly Fun Film I’ll Never Watch Again was originally published in Applaudience on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.